Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowIron Deer

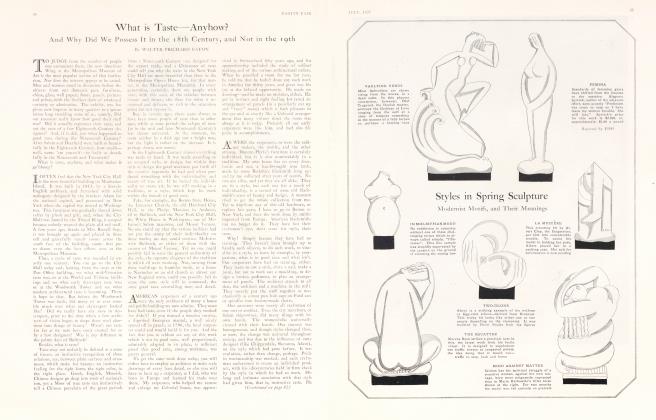

The Passing of the Unique and Distinguishing Taste of Our Forefathers

WALTER PRICHARD EATON

ONE autumn day not long ago I was walking along Bellevue Avenue in Newport. The air was soft, as it always is in that favoured section of the land, and now and then a yellow leaf drifted languidly down from the great trees. The summer procession of motor cars had vanished. For a miraculous moment, indeed, no car whatever was in -sight or sound. Then, suddenly, in the strange stillness, I heard a noise which swept my memory back through the years. Clop-clop-clopity-clop—the brisk, staccato

blows of shod hoofs on pavement! Out of an old stone gateway came a pair of bays, feeling their oats—heads high, mouths impatient of the bit, forelegs goose-stepping on parade. Behind them, on a varnished trap, sat a gentleman from another age. He had magnificent white mustachios, depending beneath ruddy cheeks, causing him to resemble a well-wined walrus. He wore a grey checked suit, a cream colored waistcoat, a salmon-pink tie, and yellow gloves. He sat up very straight, held the reins with an air, and clop-clop-clopity-clop went the turnout down Bellevue Avenue, under the great yellow trees, the ghost of an elder day. A limousine sneaked into view behind it, and purred rapidly past, with a contemptuous toot of its horn. But I noticed Old Walrus did not even turn his head. He, too, was contemptuous. He doubtless thought his horses much finer than the limousine—as indeed they were. Doubtless they wouldn't get him so far, nor so quickly. But probably he didn't want to get anywhere, and hewasn't in a hurry. Happy man!

THE contemptuous toot of that motor horn was a symbol of our present day contempt for the life, the fashions, of the day Old Walrus represented, the day of "spanking pairs," mansard roofs, hydrangea bushes, pier glasses in the parlor and iron deer on the lawn. But, like most contempts, it is based largely on ignorance, or on the quaint inability of the human animal to understand why anybody ever wanted to do anything different, or have anything different, from the actions and objects of the current hour. So we vision our Victorian predecessors as sitting primly in stuffy parlors, or moving without joy amid objects of horrid aspect, living a cramped, monotonous life in startling contrast to the gay freedom of today. Which, of course, is nonsense.

I hold no brief for mansard roofs, to be sure, if only for the reason that I once had to sleep beneath one. Much of the furniture, most of the houses, and a vast majority of the pictures created in the '70's and thereabouts were, in themselves, hideous. Some of them were so hideous that they have today a kind of grotesque fascination approximating charm! There is—or was two or three years ago—a certain hotel in the White Mountains belonging to that period, with a vast parlor displaying acres of plush upholstery and huge pier glasses framed in heavy black walnut. I always go in to look at it when I am passing by. It is incredible—and alluring.

But the houses, the furniture, the pictures, shouldn't be considered in themselves, really, but in relation to the whole social life of the times. "The Age of Innocence," Mrs. Whar-• ton called it. It wasn't so innocent (except of open plumbing) as we like to fancy. There has probably been no age of innocence since Eve's indiscretion. Because grandpa didn't know that you start a car in low, use a niblick in sand, and have a subconscious mind, it doesn't follow that he had no eye for a wench, palate for a wine, or nose for a profit. And because nobody knew how grandma kept her stockings up, it by no means follows that she was unconscious she was a female. However, that is neither here nor there. The point is that in the '70's there had grown up in America a kind of taste—good or bad as you please. —which was unique and distinguishing, and which enabled those who were financially capable of indulging it to create estates, even whole communities, set apart from the commonalty. One reason why comedies of manners (like The School for Scandal) are neither written nor appreciated any more is because they are dependent for their truth and interest upon the existence of a social group sharply distinguished by tastes and customs from the commonalty.

SUCH a group lived, in the '70's, beneath their mansard roofs and gabled towers, and behind their guardian iron deer. But such a group hardly exists in America today. The mansard roof may have given place to the no doubt much more artistic shredded wheat biscuit roof,*or the "Queen Anne" monstrosity to a carefully restored Colonial dwelling out of which every bit of comfortable ugly plush has been removed and exquisitely hard Windsor chairs substituted. The iron deer, as Allen Tucker says, may have been devoured by Italian marble lions (generally couchant after their meal). The hydrangea bushes, in great billowing clumps, may have yielded to carefully planned beds of tuberous rooted begonias, delphiniums, iris, schyzanthus, or whatnot delicate flowers. The steel engraving in the hall of Washington's first reception, the landscape in the parlor of a rainbow over the Highlands of the Hudson, may have yielded place to a Piranesi and an Arthur B. Davies. But a certain distinction has gone from our life, just the same. The towers of the Squire's house no longer dominate the village, the clopity-clop of his pair no longer dominates the village street, his taste no longer dominates the styles. There can no longer be high comedy in our literature because there is no clearly marked group of the socially superior so set apart in their ways as to be the object of understandable ridicule. In the old days, the iron deer were almost as much the mark of social superiority as the two lamps flanking the front stoop were the mark of an ex-Mayor in New York. It was only natural to wonder who lived behind them. Now, when you see a marble lion, couchant, or a concrete cupid carefully concealing his sex with a bunch of grapes, you merely wonder which landscape architect (so called) was employed—and why!

I drive along, and occasionally I still see a pair of iron deer surmounting stone gate posts, or stalking on the lawn. Sometimes it is an iron dog. And almost invariably they mark a Victorian estate which has somehow survived the changing styles, and shows us what once was. Such estates for the most part are conspicuous for a su'eep of greensward, for tall arching trees, for a big, evidently roomy house set down commandingly at the head of the drive, not in the least trying to conceal itself, but nevertheless withdrawn from the road somewhat haughtily. There are always stables in the rear. The house is usually hideous—as a piece of architecture. But its setting, its manner of holding itself, is the setting and manner of George Washington's Mount Vernon, just the same. It is the English country squire's park modified to the American scene, even the American town street. It is not the effort of the very rich to create an estate, of the very artistic to create a beautiful effect, of the very vulgar to show off. It is the embodiment of a certain social ideal of solid comfort, good living, and the proper exclusiveness. Such a place, in spite of the house, almost invariably has a beauty of its own, and when the house happens to be a little earlier in date than the mid-19th century, belonging to the Doric period which followed Jefferson's influence, it can beat for sheer attractiveness all your modern landscape-architected and formalgardened and whitewashed bricked estates, making them look like parvenues.

Continued on fage 94

Continued from page 44

In the good old iron deer days, a man w'as known, too, by the horses and carriages he kept. They marked him out, set him apart, for who and what he was. The farmer's carryall, the livery stable rig, the doctor's buggy, could never be mistaken. And no more could the brougham or the coach or the trap from the big house. Ordinary townsfolk didn't have any horses at all. But now everybody has an automobile, and the best cars sometimes belong to the worst people; and, anyhow, they are usually in the towns where they don't belong and nobody knows anything about their occupants. Almost the only sure sign of "the quality" to be detected from motor cars is the sight of an ancient Pierce Arrow, with the paint still good though the scats are six feet above the road, driven by an even more ancient chauffeur who looks like an excoachman (and probably is) at the rate of 17 miles per hour, while two old ladies sit stiffly in the rear, and glare at you when you toot your saucy Gabriel horn and scoot impatiently by them in your low-hung, streamline roadster. Buy a new car? Of course they could. They could probably buy a dozen. They could buy new curtains, too, for the drawing room, and new pictures to replace the rainbow over the Hudson and Washington's reception and Grandfather Amos's portrait, and new stone lions to replace the iron deer, and even build a new house to replace the grimly gaudy Victorian pile they live in. But they won't. Not a chance. They belong to an age, a society, that acquired—acquired a lot, spent enough to be amply comfortable and to make the proper showing to keep the hoi polloi in place, and then kept and consolidated what it had as if nothing was going to change again. This age, this society, didn't want change. It hated change. It was thoroughly and frankly Tory. It considered itself to compose the best families, the best minds, of the country. And, curiously enough, for the most part, it was right.

That last statement will, I suppose, be greeted with a contemptuous snort by many readers. To say, in this generation, that the best families and the best minds arc found in the big houses behind the marble lions would be, of course, to invite contempt. But times, like tastes, have changed. What America is looking for today is not a consolidation of its resources, a stabilizing of its crude society, but spiritual leadership in the conquest of industrial materialism.

On a back road, far up in the State of Maine, in a region of tumbled hills and rocky farms, there stands a big house, cut up with towers and plate glass windows and gingerbread ornamentation, a perfect sample of the iron deer age. It was built by the author of tremendously successful boys' books back in the '70's and '80's, and built out of the proceeds. I was one of the American boys brought up on those books. I got my love of the Maine woods directly from them. The author wasn't a snob or a parvenue; quite the contrary. But when he got his money, he expressed in his house his inborn conviction that rooms should be large enough to swing a cat in, that a man has a right, if he can, to live spaciously and well. If that man had sons or daughters, who built homes in Maine today, they would build much smaller houses than his (as, indeed, they would have to, unless they were enormously rich), and these houses would probably be carefully restored Colonial dwellings or else constructed of the native granite ficldstone, prettily fitted into the landscape. Neither you nor I, certainly, could live in father's house without acute agony every time we had to look at it.

So the Toryism of the iron deer turns out to be a paradox, and was really a necessary stage in our democratic evolution. The deer were not so much a symbol of exclusiveness as of success in attaining the universal goal of solid comfort, ample living, spacious enjoyment. I make no claims for the nobility of this goal. But it was honest, and it was certainly American. In spite of the modern laughter at the iron deer and all they represent, I rather fancy it is American still. At any rate, if it had not existed, and if it had not been attained by social groups through the country, America today would be a far less comfortable place for you and me to be artistic in. For that matter, you could probably never have gone to study art in Paris at all. You would probably still be a carpenter in Skowhegan.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now