Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowOur Colonial Ancestors

Life in America When Antiques Were New and Our Passions Tempered

WALTER PRICHARD EATON

IN 1776 the American colonists were a lively, comfortable, intelligent, and almighty independent people. In the New England end of the Colonies they were already lanker than their British cousins, talked through their noses, couldn't spell, and combined a shrewd sense of humour with considerable serious-mindedness. In the middle of the Colonies, in Philadelphia, there were prosperous and "worldly" folk who lived in beautiful houses, there were sober Quakers, and there was the usual artisan class. In the southern end were the Carolina and Virginia planters, hospitable English squires who had developed independence and ability in the new world, and the Roman Catholics of Baltimore, intellectually the most tolerant and broadminded of all the colonists. There was money in America even in 1776. Boston, probably the richest city, had about 25,000 people, and many splendid houses, of which the most beautiful was John Hancock's on Beacon Hill. But there were fine houses in the country, too, such as the Royall house in Medford.

FOR years colonial merchants and planters —the Fancuils, the Bromfields, and so on, in Boston; the Cadwalladcrs and Powels and Morrises in Philadelphia; the Washingtons and Byrds in Virginia—had been importing silk-and-wool damask curtains, Chinese wall paper, Chelsea and Bow china, and all manner of lovely things, which in combination with the beautifully designed and built Georgian houses and the fine mahogany furniture and the silverware, too, converted their homes into places of extreme beauty, elegance, and even luxury. The Robinson house near Narragansett, R. I., was 110 feet long, with extensive slave quarters, and its proud, domineering owner, long before 1776, had become a rich man trading in horses, in cheese, in grain, and engaging in shipping, too. There was, of course, a distinct social cleavage in those days, between the clergy, merchants and squires on the one hand, and the artisans and common folk on the other. But even then British caste was fading, though in matters of taste aristocracy still ruled; for almost anybody might become a squire, or marry a squire's daughter, and because land was cheap and plentiful the humblest man was tremendously conscious of his worth and independence, looked forward to getting luxuries like those the aristocrats had, spoke his mind in town meeting, threw the tea into Boston harbour though it was consigned to a Bromfield, and blithely started the American Revolution though every aristocrat in the Hub was a Tory except John Hancock.

Carl Percy, heir to the dukedom of Northumberland, was the field commander of the British troops quartered in Boston in 1775-76. He rented (or took) a house on Winter Street to entertain in, paid £350 for a horse, and rode about the country, writing back to his father that New England was a lovely land, and the Charles much fairer than the Thames. All he objected to was the cantankerous and utterly unrespectful attitude of the inhabitants!

IT was a lovely land. So was the valley of the Potomac, and the James, and the Delaware, and the Hudson. Superb virgin pine was everywhere abundant with which to build houses; the carpenters were well trained in the splendid Georgian style, which was accepted by everybody, and could make even a simple farm house beautiful. Maple, oak and hickory were equally abundant for fuel, and while bed chambers must often have been bitterly cold, the great fireplaces of the kitchens and living rooms, supplied with wood as good as any anthracite, were genial and warm. The virgin meadows were rich with hay, the cattle were fat, the farms and plantations were all supplied with sheep and with looms, and clothes were all wool and a yard wide. Skins, too, were abundant. Even our humblest ancestors, except during the stress of the Revolution, lived quite literally on the fat of the land. I have ancestral recipes which call for such items in cake or pudding as "18 eggs, 2 quarts yellow cream," etc. They ate well, and they drank well, too. Dear old Parson West, who followed Jonathan Edwards as minister in Stockbridge, Massachusetts—then a frontier town—and who blessed the soldiers when they marched to the siege of Boston, left behind him some account books which I have seen. In one of them is a record of his purchases of rum, for two years. He got one pint at the store every day except Saturday and Sunday. Sunday, of course, he bought none; but every Saturday he bought a quart! Yet he was a goodly and God fearing man. In the squire houses and the towns they drank Madeira and Port. When Washington stopped for dinner at Gatsby's Tavern in Alexandria he ordered canvas backs, "a chafing dish, some hominy, a bottle of good Madeira," and added, "we shall not complain."

Well, I should hope not!

And they hadn't expected him, either. This was on the regular menu.

Our ancestors had no bathrooms. Some of their personal habits would shock us now. And they knew nothing of sanitation. They got their water from wells, even in the cities, and paid little attention to the proximity of sink drains and privies. The result was epidemics of what we now know as typhoid, but which they called "summer fever". Infant mortality was high, too, and the survival of the fittest (or the luckiest) was in full operation. But, on the other hand, in spite of diseases and the mortality among wives from too much child bearing and lack of proper knowledge, a large number of our ancestors lived to an extreme old age, and neurasthenia was an unknown affliction. I had a great-grandmother who lived to be 102 years and 11 months. The truth is that our ancestors worked hard, were much out of doors, ate good food, and kept their minds alert. When they weren't debating the Stamp Act or planning a Revolution, they were debating religion and salvation. They were tremendously energetic, ambitious and intellectually alive.

IT is as ridiculous an error to suppose, too, that our Colonial ancestors were a dour and glum and long faced and dull people, as it is to suppose that they lived in barren houses, without comforts and without beauty. The latter idea, of course, we are fast getting rid of, as we discover more and more the exquisite charm of Colonial architecture and furniture in the fine houses, and the simply dignity and warm comfort of the pine and maple and hooked rug and patchwork quilt interiors of the humbler homes. It takes longer to get rid of the other error.

In 1774, just before the Revolution, and just before John Singleton Copley transferred his studio from Boston to London (thus presaging the career of John Singer Sargent a century later), the Reverend Mather Bylcs, Tory, scion of the great ecclesiastical houses of Mather and Cotton, and pastor of the Hollis Street Church, (now a theatre), met a friend with a toothache.

"Where can I get this tooth drawn?" said the friend. So Bylcs gave him an address on Beacon Street. He went to the house, in its 11-acre garden, and knocked. It was the studio of Copley! This same Dr. Bylcs, who lived on Tremont Street, complained in vain about the mud before his dwelling. One day he saw two of the Selectmen stuck in it, and trying to pry their chaise loose. Going out on his steps, he* shouted, "Gentlemen, I'm glad to see you moving in this matter at last!" Their reply is not recorded. After the evacuation of Boston in 1776, Byles was put out of his church, as a Tory, and a sentry set on guard in front of his house. The sentry was removed after a few weeks, then put back, then finally called off altogether. "I have," said the divine, "been guarded, reguarded, and disregarded." Neither Byles'famous grandfather, Increase Mather, nor his famous uncle, Cotton Mather, could have said just this, to be sure. But until Tory proclivities turned the town against him, Byles' wit was a constant source of joy in Boston. He was the Holmes of his day. His friend, Ben Franklin, was not exactly a glum creature, either, and the England which in 1775 could produce Sheridan and "The Rivals" could, and did, produce colonists quite capable of seeing a joke, or making one.

Continued on page 92

Continued from page 43

Moreover, it is entirely erroneous to suppose that the grim theology of Calvin and the Pilgrim Fathers persisted in force till 1776. It is safe to say that the average American in 1776 didn't feel himself a worm at all. He wasn't a worm—and by heck he could prove it! He could prove it by philosophy, the Bible—and a rifle! So Whitefield, coming to America to save our souls, complained that Harvard College was a hotbed of infidelity and radicalism, Jonathan Edwards bemoaned the degeneracy of the times, and the rich Tories, comfortable in their beautiful houses, like Tories everywhere and always, didn't approve of "new ideas" and tall talk of defiance; but the rank and file of Americans in 1 776 were mentally, morally and physically self reliant, on their toes, with faces toward the future. There was probably more intelligent thinking and ardent feeling among our people at that time than there has ever been since. There could even be a dash of the high romance. When "Crazy" Harry Babcock went to England (before the war, of course) and met the Queen, he rose from his knee as she extended her hand, exclaimed, "May it please your Majesty, in my country, when we salute a beautiful woman we kiss her lips"—and seizing the astonished monarch by the shoulders gave her a hearty smack. Upon his return to America, he went to Narragansett to see the famous beauty, Hannah Robinson. Before her he kneeled, took her fingers, and said, "Pray permit one who has kissed unrebuked the lips of the proudest Queen on earth to press for a moment the hand of an angel from Heaven!" After all, Charles Surface couldn't have done so well—because he would never have dared to kiss the Queen!

Except for the arts of the craftsman, of course, Colonial America had done little to develop aesthetic resources. A few portrait painters, like Copley, had risen to meet a demand, but that was about all. Men who in a later day would have been literary artists became ministers, and the writing and oral delivery of sermons was undoubtedly a source of artistic satisfaction both to ministers and congregations. The pulpit was dramatized, though quite unconsciously. That still happens in many parts of America, remote from other sources of entertainment. There was little journalism, though Franklin was blazing a trail. Political and philosophic pamphleteering, however, played a large part in national life, and men like Tom Payne and Jefferson developed very considerable powers. Puritan New England was without a theatre, thanks to the traditions the Colonists had brought from England. But there were theatrical performances in Charleston, S. C., as early as 1739, and in the middle of the century Hallam brought a company of English professionals to the new world, and acted in Virginia, Philadelphia and New York. Later his successor, David Douglass, acted up and down the seaboard, in crude improvised theatres no doubt, and even made one attempt to storm New England. He got away with a season in Newport, R. I., but in Providence he was stopped by act of the Legislature. The sheriff who came to stop the performance arrived on time, saw the play through, and then delivered his closing notice!

In 1775 all places of amusement in the Colonies were closed by order of the Continental Congress, thus preventing Douglass from playing a season, as planned, at the John Street Theatre, New York. His last season in America—the winter of 1773-74, was spent at Charleston, S. C., in a new theatre erected for him. The repertoire would quite stagger any American company today. Fifty-six performances were given, each bill consisting of a long play and a farce, and a total of nearly eighty different plays, short and long, were acted. These plays included Hamlet, The Beaux Stratagem, Congreve's The Mourning Bride, She Stoops to Conquer, Jane Shore, Cymbeline, Romeo and Juliet, The Tempest, The Merchant of Venice, Richard III, Othello, King Lear, Macbeth, Julius Caesar and The Provoked Husband. The South Carolina Gazette at the end of the season declared the theatre had been "warmly countenanced and supported" and praised highly the work of the company. In addition to this varied theatrical fare, Charleston had regular concerts by the Saint Cecilia Society, one of which Josiah Quincy of Boston attended, and was amazed to find 250 ladies present, much superior in dress to his New England acquaintances and greatly excelling the Yankee women, too, "in taciturnity during the performance."

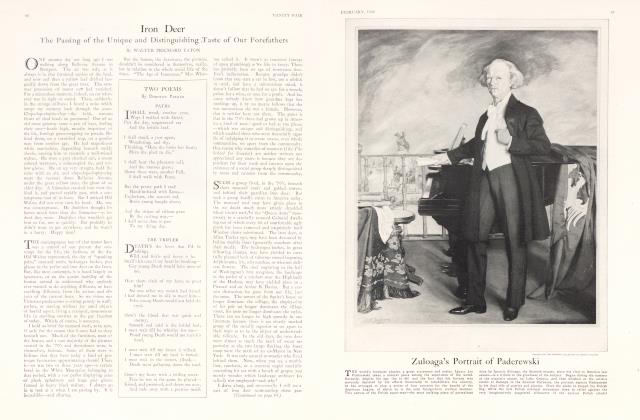

A CELEBRATED SIGNATURE This signature of Button Gwinnett, Georgia representative in the Continental Congress, was affixed to a legal document in 1774. It recently sold for $22,500, the highest price ever paid for a single autograph

Continued on page 105

Continued from page 92

Then, of course, in Charleston and all other Colonial cities there were rather stately balls and parties. Certainly a city the size of Charleston in 1773, which supports a winter repertoire of 56 bills, and concerts in addition, is not exactly pining away for entertainment. And, so far as Charleston is concerned, it is quite safe to say that it had a far better theatre in 1773-74 than it has in this year of grace, 1926! That theatrical repertoire would have been repeated and extended in New York in 1774-75, and in Philadelphia in 1776, had the war not intervened, and Williamsburg, Virginia, Annapolis, and some other cities would have had a taste of it, too.

There were some barbarous customs still left in 1776, such as shift marriages. It was generally a widow who was married in her shift. Clad only in this one garment, she crossed the road to the waiting groom and parson and the necessary and perhaps embarrassed witnesses, thus to signify that her new husband didn't have to pay any of her former husband's debts. There were shift marriages in Rhode Island into the 19th century. It seems to have been a case of thrift as well as shift! There were cruel and excessive punishments still in force, too, for what now look like very minor crimes. Insanity was often regarded in a humorous light, and a. woman's worth still was too often reckoned in terms of fertility. But private property was generally considered sacred, and whole communities never locked their doors. (They don't to this day on Nantucket Island.) Men and women had passions then as now, and one didn't grow up without peril.

But the general tone of the communities was still strongly moralistic, in all the Colonies; the lost terrors of Calvinism had not meant the loss of the "ethic ought", all meetings still began with prayer, and even the most worldly men could not escape the surrounding sense of other-worldliness, of religious compulsion. That, with the intellectual alertness of the population, and their swelling sense of independence and potential power and dignity, made for a race of peculiarly active, self-directed, well-intentioned people, whose lives may have lacked many of the comforts, the luxuries, the mental and aesthetic stimulants, we enjoy today, but who were compensated for this lack by a certain deep and earnest zest in existence which seemed to them divinely ordained by the laws of God and Man. When the Liberty Bell pealed in 1776 it struck an emotional chord in American bosoms that can perhaps never be reached again. Their minds were ready, their hearts were ready, and they had talked with God.

On the whole, not a bad time to have lived in!

EDITOR'S Note:—Walter Prichard Eaton, the author of the above article, is an authority on the history of early America. Few men are so well informed on the Revolutionary background, whether aesthetic, political or sociologic. Mr. Eaton has rendered invaluableaid in the planning and preparation of this Sesqui-Centennial number.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now