Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

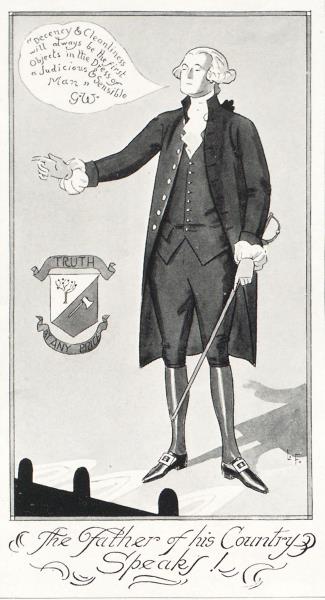

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWith Actual Letters Concerning His Clothes by George Washington

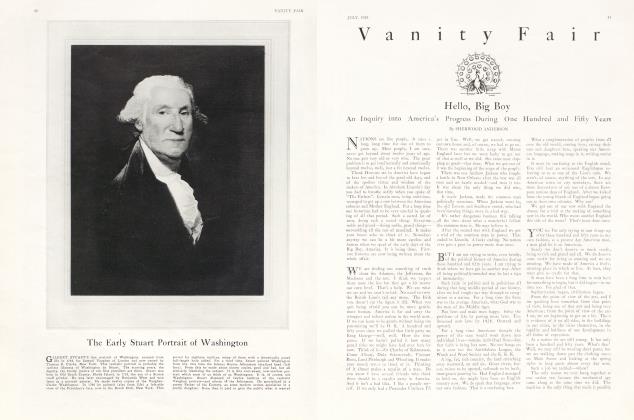

July 1926 Lawrence Fellows THE WELL DRESSED MAN OF 1776 At his second Inauguration, General George Washington was attired in a suit of black velvet, the breeches being caught at the knee with diamond knee buckles. His patent leather shoes had silver buckles and his hair was powdered in a bag. His light sword was carried in a grey scabbard for dress occasions

THE WELL DRESSED MAN OF 1776 At his second Inauguration, General George Washington was attired in a suit of black velvet, the breeches being caught at the knee with diamond knee buckles. His patent leather shoes had silver buckles and his hair was powdered in a bag. His light sword was carried in a grey scabbard for dress occasions

IN the days of '76 the importance of being well dressed was a subject of keen interest to the men of America. In fact, during the latter half of the eighteenth century this was true because it was at this period, and undoubtedly brought on by the exigency of war times, tha: men's attire began to change from the picturesque costume of perukes, ruffles and laces, short breeches and silk stockings, to the more democratic and certainly more practical garments which were the forerunners of our present day styles in men's fashions.

This interest in clothes extended to all classes and the extreme importance attached to the most minute details of dress is clearly shown in the correspondence of our first well dressed man, George Washington, who from the days of his early manhood showed a fondness for dress. Even at the tender age of fifteen this characteristic had already developed, for in 1747 he wrote the following explicit instructions to his tailor in London:

"Memorandum. To have my coat made by the following Directions, to be made a Frock with Lapel Breast. The Lapel to contain on each side six Button Holes to be about five or six inches wide all the way equal, and to turn as the Breast on the coat docs, to have it made very long waisted and in Length to come down to or below the bend of the knee, the Waist from armpit to the Fold to be exactly as long or Longer than from thence to the Bottom, not to have more than one fold in the Skirt and the top to be made just to turn in and three Button Holes, the Lapel at the top to turn as the Cape of the Coat and Button to come parallel with the Button Holes and the Last Button Hole on the Breast to be right opposite the Button on the Hip."

Indeed, throughout his life, his love of fitting and rich attire was never dimmed by affairs of war or state. In his orders to England, Washington always laid great stress upon the necessity of having his clothes made in the latest modes of the reigning fashion. Nor was Washington alone in this respect because even the signers, of the Declaration of Independence showed no republican simplicity in their attire, but, along with other Revolutionary heroes, were equally vain and vied with judges, doctors, and merchants in rich and carefully studied attire.

BANYAN DRESSING GOWN In Virginia and the Southern Colonies the hot wigs and stiff, cumbersome garments prescribed by fashion were uncomfortable for daily wear in the summer season; so much so that men wore banyans and caps made of calico or damask in the street and at home

BANYAN DRESSING GOWN In Virginia and the Southern Colonies the hot wigs and stiff, cumbersome garments prescribed by fashion were uncomfortable for daily wear in the summer season; so much so that men wore banyans and caps made of calico or damask in the street and at home

BOOTS Two types of boots were favoured by the citizens of the New Republic in 1776—one boot being cut higher in front so as to afford greater protection which was worn largely by the troops, the other being more like our modern riding boot but with a deep cuff at the top

BOOTS Two types of boots were favoured by the citizens of the New Republic in 1776—one boot being cut higher in front so as to afford greater protection which was worn largely by the troops, the other being more like our modern riding boot but with a deep cuff at the top

During the eighteenth century periwigs and cocked hats were the characteristic features of the dress of the men, and the following advertisement which appeared in the Pennsylvania Gazette in 1773, gives an amusing picture of the importance of hair at that time. "William Lang, Wigmaker and Hair dresser, hereby informs the public that he has hired a Person from Europe by whose assistance he is now enabled, in the several Branches of his Business, to serve his good customers, and all others, in the most genteel and polite tastes that are at present in Fashion in England and America. In particular, Wigs made in any mode whatever, such as may grace and become the most important Heads, whether those of Judges, Divines, Lawyers or Physicians, together with all those of an inferior kind, so as to exactly suit their Respective Occupations and Inclinations. Hair-dressing, for Ladies and Gentlemen, performed in the most elegant and Newest Taste—Ladies in a particular Manner, shall be attended to, in the nice, easy, genteel and polite Construction of Rolls, such as may tend to raise their Heads to any Pitch they may desire, also French Curls, made in the neatest Manner. He gives Cash for Hair."

POUR LE SPORT The huntsman, in 1776, wore a long full skirted jacket buttoned right up to the neck, with cuffs that could be rolled back. His jockey-like cap fitted close to the head and had a long vizor which turned up. Gauntlets and long leather leggings completed the costume

POUR LE SPORT The huntsman, in 1776, wore a long full skirted jacket buttoned right up to the neck, with cuffs that could be rolled back. His jockey-like cap fitted close to the head and had a long vizor which turned up. Gauntlets and long leather leggings completed the costume

From an authority we learn that, "Under Queen Anne the hats worn by men were smaller and were regularly cocked on three sides, and the cuffs of the coat were very wide and long, reaching almost to the wrist. The broad sword belt had vanished and the sword belt could be seen beneath the stiffened skirt of the square cut coat. Blue or scarlet stockings, with gold or silver clocks, were much worn, as were also shoes with red heels and small buckles; velvet gaiters were worn over the stockings below the knee, fastened on one side by small buckles. Campaign wigs imported from France now became popular. They were made very full with long curls hanging towards the front. When human hair was scarce, a little horsehair supplied the place, in the part least in sight."

In 1706 a peculiar cock of the hat came into fashion called the Ramilie, and a long plaited tail to the wig with a great bow at the top and a small one at the bottom known as the Ramilie Wig.

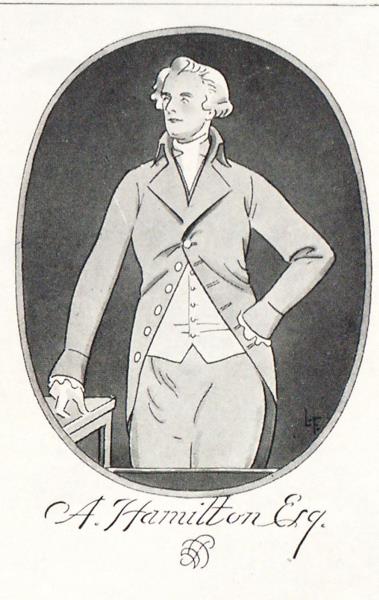

LACES AND RUFFLES Despite the fighting times of the 18th Century, men paid great attention to dress and fashion and the sword knot received as much attention as the sword. Waistcoats were left unbuttoned at the top in order to display beautiful lace, in ruffles and neckties, which were pet extravagances

LACES AND RUFFLES Despite the fighting times of the 18th Century, men paid great attention to dress and fashion and the sword knot received as much attention as the sword. Waistcoats were left unbuttoned at the top in order to display beautiful lace, in ruffles and neckties, which were pet extravagances

Those who did not wear powder and who objected to the enormous expense or weight of the fashionable wigs, wore their own hair in long curls to resemble them, but the long popularity of the uncomfortable fashion of the periwig is indeed astonishing.

Dr. Granger, in his life of Charles II, speaking of the fashion when it first came into vogue, says: "It was observed that a periwig procured many persons a respect and even veneration which they were strangers to before and to which they had not the least claims from their personal merit," and he quotes the amusing anecdote of a country gentleman who employed a painter to place periwigs upon the heads of several of Vandyke's portraits. Large wigs were worn until the middle of the 18th century. A plain peruke imitation of a natural head of hair was called a short bob.

A beau of this time is spoken of as "appearing in a different style of wig every day, and thus perplexing the lady to whom he was paying his addresses, by a new face every time they met during the first months of their courtship." Hats could be moulded in so many different cocks as to change the whole appearance of the wearer.

CLUBMEN OF OLD NEW YORK The beaux of old New York wore suits of silk, velvet, or fine cloth, the long coat ending just below the breeches; silk stockings, buckled shoes and waistcoats of fine embroidered brocade were in favour

CLUBMEN OF OLD NEW YORK The beaux of old New York wore suits of silk, velvet, or fine cloth, the long coat ending just below the breeches; silk stockings, buckled shoes and waistcoats of fine embroidered brocade were in favour

In 1760, when wigs were powdered, they were frequently sent for that purpose in a wooden box to the barber to be dressed on his block-head. "Brown wigs", for which a brown powder was used, were worn, but were less fashionable than the "white disguise". On ceremonious occasions, if wigs were not worn, the hair was craped, curled, and powdered by barbers.

About 1770, when wigs went out of favour and the natural hair was preferred, it became the fashion to dress it in a queue, or to wear it in a black silk bag tied with a bow of black ribbon. With the queues belong fizzled sidelocks, and toupees formed of the natural hair, or, in the absence of a long tie, a splice was added to it. Such was the general passion for the longest possible whip of hair, that sailors and boatmen used to tie theirs in eel skins to aid its growth.

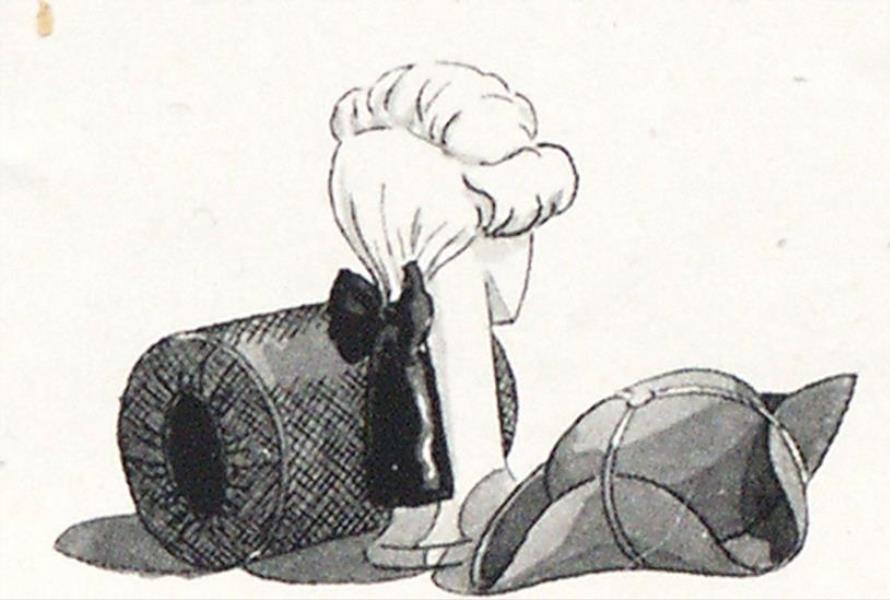

MUFFS FOR MEN Muffs for the protection of masculine wrists, bobbed wigs and large three cornered hats were among the accessories of men's wear

MUFFS FOR MEN Muffs for the protection of masculine wrists, bobbed wigs and large three cornered hats were among the accessories of men's wear

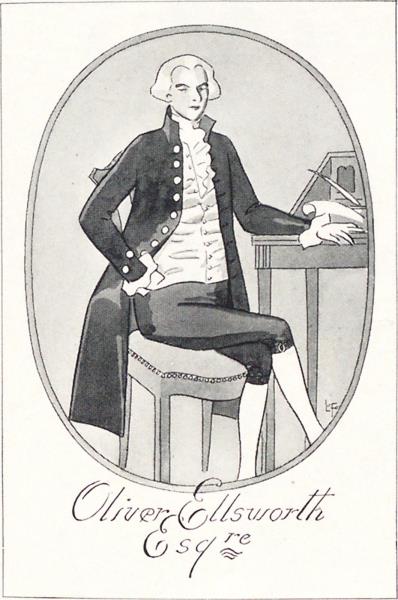

TRANSITION STYLES After the revolution, men's dress became a little more simplified. Wide lapels made their first appearance along with the upstanding roll collars on the coats which fell away in much the same manner as our modern single-button cutaway. Stocks of fine linen became much less elaborate

TRANSITION STYLES After the revolution, men's dress became a little more simplified. Wide lapels made their first appearance along with the upstanding roll collars on the coats which fell away in much the same manner as our modern single-button cutaway. Stocks of fine linen became much less elaborate

An interesting silhouette of Washington by Folwell shows him with what is supposed to be a fine net worn over hair and queue to keep the powder in place. In 1759 he ordered from England for his own use; "A New-Market great coat with a loose hood made of Blew Drat or broadcloth with straps before, according to the present taste—let it be made of such cloth as will turn a good shower."

The first umbrellas to keep off the rain were of oiled linen, very coarse and clumsy, with rattan sticks. Before their time, some physicians and ministers used an oiled linen cape hooked around their shoulders, looking not unlike the big coat-capes now in use. They were only used for severe storms, like modern water-proofs. In about 1771 the first efforts were made in Philadelphia to introduce the use of umbrellas in summer as a protection from the sun. They were then scouted in the public Gazette as a ridiculous effeminacy.

In Watson's Annals of Philadelphia, we read: "Coats of red cloth were considerably worn, even by boys, and plush breeches and plush vests of various colors were in common use. Everlasting, or durant, made of worsted, was a fabric of great use for breeches, and sometimes for vests which had great depending pocket flaps, and the breeches were very short over the stude, because the art of suspending them by suspenders was unknown, it was then the test of a well-formed man, that he could by his natural form readily keep his breeches above his hips, and his stockings without gartering, above the calf of the leg."

"In the time of the Revolutionary War, many of the American officers introduced the use of Dutch blankets for great coats. Large silver buttons worn on coats and vests were a mark of wealth. Some people had the initials of their names engraved on each button. Sometimes they were made out of real quarter dollars, with the coinage impression still retained; these were used for the coats, and the eleven-penny-bits for vests and breeches.

Mr. Sidney George Fisher, the historian, despite his Quaker ancestry, exclaims with unwonted enthusiasm "Those were brave days when the judges on the bench wore scarlet robes faced with black; when the tailor shops, instead of the dull coloured woolens which they now offer, advertised, as in the New York Gazeteer of May 13, 1773, scarlet, buff, green, blue, crimson, white, sky-blue, and other coloured superfine cloths; when John Hancock of penmanship fame, is described in his home in Boston with a red velvet skullcap lined with white linen which was turned over the edge of the velvet about three inches deep, a blue damask dressing-gown lined with silk, a white stock, satin embroidered waistcoat, black satin breeches, white silk stockings to his knees, and red morocco slippers."

Mufftees, or little woolen muffs of various colours, were used by men In the colonies. They were "just big enough to admit both hands and long enough to screen the wrists, which were then more exposed than now; for they wore short sleeves to their coats on purpose to display their fine plaited linen shirt sleeves with thin gold cuff buttons and on occasions ruffles of lace."

Watches were worn in fob pockets with seals attached by a ribbon, but they were not in common use until the end of the century.

Although the style of living in colonial New York was comfortable, with little display, when we come to the subject of dress we find the case was very different. Early in the 18th century, the streets of New York were gorgeous with elaborate costumes. Gay masculine garments are described in inventories. Green silk breeches, flowered with silver and gold, silver gauze breeches, yellow fringed gloves, lacquered hats, laced shirts and neck cloths.

From 1760 to 1770 gentlemen in Massachusetts were wearing "hats with broad brims turned up into three corners with loops at the sides; long coats with large pocket-folds and cuffs, and without collars. The buttons were commonly plated, but sometimes of silver, often as large as a half dollar. Shirts had bosom and wrist ruffles; and all wore gold or silver shirt buttons at the wrist united by a link. The waistcoat was long, with large pockets; and the neck-cloth or scarf was of fine white linen or figured stuff broidered and the ends hanging loosely on the breast. The breeches fitted close with silver buckles at the knees. The legs were covered with gray knitted stockings which on holidays were exchanged for black or white silk. Boots with broad white tips, or shoes with straps and large silver buckles, completed the equipment."

According to Fairholt, the costume of the ordinary classes during the greater part of the 18th century was exceedingly simple, consisting of a plain coat, buttoned up the front, a long waistcoat reaching to the knees, but having capacious pockets with great overlapping flaps, a plain bob-wig, a hat slightly turned up and high quartered shoes.

In a paper of 1771, a reward of ten pounds was offered for the arrest of a man named William Davis who robbed the church of Wilmington of its hangings and had a green coat made of them. Green was very fashionable at this period.

As in all ages and climes, variations of the prevailing style were indulged in by gay young men about town. The pet extravagance at this period was beautiful lace in ruffles and neckties.

Fairholt, in his History of English Dress, says: "By the cock of the hat, the man who wore it was known; and they varied from the modest broad brim of the clergy and the countryman to the slightly up-turned hat of the country gentleman or citizen, or the more decidedly fashionable cock worn by merchantmen, and would be-fashionable Londoners; while a very pronounced á la militaire cock was affected by the gallant about the Court." All of these styles may be seen in the pictures of Hogarth. These hats were usually made of soft felt with a large brim caught up by three loops of cord to a button on the top. Being soft, they could be crushed under the arm and each flap could be let down at pleasure in case of wind, rain, or sun. Mr. Wingfield speaks of a hat "unlooped although it doth not rain", and observes that in one of Cibber's comedies we find a footman "unlooping his hat to protect his powdered head from the wet". To use the snuffbox gracefully was an accomplishment considered necessary to the young man of fashion on his entrance into the gay world of the 18th century. Made of every sort of metal, adorned with precious stones or costly miniature paintings, the snuffbox was in great demand, and considered as indispensable on occasions of full dress as the fan.

It is strange perhaps to find Washington dwelling so much on these superficial things during the solemn days of his vast responsibility and great apprehension, in the early days of the Revolution, and even in the first working years of the Republic, but great things and petty jostle each other. On the 4th of July, 1776, the day Thomas Jefferson signed the Declaration of Independence; on that eventful day Jefferson's sole entry in his day book and in his own "Signer's" hand is this item, "For seven pairs of women's gloves, 20 shillings."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now