Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Games of Our Forefathers

How America Played Poker, Whist, Billiards and Craps 150 Years Ago

R. F. FOSTER

WHAT were the games that were the favourite amusements of men like George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton and the others whose names arc famous in connection with the Revolutionary days of 1776?

Well, we know that while Washington's tastes ran more to exercise than to sedentary games he was particularly fond of Billiards, and a billiard table that was once his property, together with another that belonged to Alexander Hamilton, were recently put on exhibition in New York.

We also know that Benjamin Franklin added greatly to his popularity in Paris in 1767 by introducing the American card game, Boston, which had a great run in its day, but is now never heard of; probably because of the complications of scoring.

It is difficult for us to imagine the conditions under which indoor games were played 150 years ago. In the first place, the lighting was very poor, the only illumination being from tallow candles, that required constant snuffing. The billiard tables had no elastic cushions and the cues had no tips. What we call pockets were simply holes at the edge of the table.

The playing cards manufactured in America, in those days, were the same size as those of today, and of good linen stock. The court cards were all single heads and all the marking was stenciled by hand. The backs were always plain white. I have in my possession a pack of these cards, manufactured by Thomas Crehore, the backs of which particular pack were used to print the invitations for a dance at Yale University. One of these reads: "Examination Ball, at the State House, Wednesday, 7 p. m., July 20th, 1785. Managers: J. Henshaw, S. Huntington, R. J. Meigs." A pack of these cards was about twice as thick as those we use now.

IF we go back to the card games that were played 150 years ago, we find some of them that were then played (in their elementary form) in the servants' hall that arc now the favourites in the world of fashion; while games which were then the only correct thing in polite society, such as Quadrille and Ombre, arc now not considered worth even a paragraph of description worthy of inclusion in any of our modern Hoyles.

Among the card games, some member of the Whist family, played with fifty-two cards, has been a reigning favourite in society for 180 years. But when the game which we now call Whist was first played, before 1740, only fortyeight cards were dealt, one of the remaining four being turned up for the trump. Whoever held the ace of trumps could take these four cards and discard four in their place, just as the highest bidder now does in Auction Pinochle. This game was variously called Triumph, or Ruff and Honours. In 1680, Swabbers came into vogue; four cards that entitled the holders to share in the stakes.

These various forms of the game of Whist were apparently played only by the lower classes and card sharpers, as they wrere simply gambling devices, the "science" that lay hidden in the game, and its possibilities for intellectual recreation, being then undreamed of. Rabelais mentions Triumph in his long list of the games played by Gargantua. Berin tells us that the game was played only by peasants, and Eliot calls it a common ale-house game. Shakespeare makes no mention of Whist, but that he was familiar with its forerunner, Triumph, is evident from Antony and Cleopatra, Act IV, Scene 12.

About the beginning of the eighteenth century they began to deal out the whole fifty-two cards. In that form attention was soon attracted to the intellectual possibilities of the game and it soon climbed upstairs from the servants' hall to the drawing room. Some gentlemen that were in the habit of meeting at the Crown Coffee House in Bedford Row, London, guided by the genius and enthusiasm of Viscount Folkestone, soon reduced the game to something like scientific principles of play and called it Whist.

Among that set was one man whose name is still synonymous for everything that is correct in games of cards, Edmund Hoyle, who gave to the world in 1742 his Short Treatise oti the Game of Whist, of which the only known copv of the first edition is now in the Bodleian Library at Oxford. Only one authentic portrait of the author is known, which was found on a medal in an antique shop in Brighton by Mr. Frederic Jessel, the author of Playing Cards and Gaming. A copy of this medal is reproduced with this article.

Hoyle was apparently the first person who ever gave lessons in Whist, and in the Rambler, for May, 1750, one of his pupils mentions having taken forty lessons from him at a guinea each. He made the same charge "for explaining any of the points in his book", and for imparting a system of artificial memory he had designed for card players. It is interesting to note that "the father of Whist", as he is generally called, lived to be ninety-seven.

Besides Hoyle and Folkestone, there were two other men whose fame will probably last as long as the game they loved. One of these was Lord Yarborough, who used to cut short anyone who complained about being a poor card-holder by offering to bet him a thousand to one that he would hold at least one card above a nine; the real odds being 1827 to 1.

Another famous character was Lord Henry Bentinck, who used to play at Graham's Coffee House, 87 St. James Street, London. It was in 1834 that he invented the trump signal, which was humorously referred to in those days as the "blue peter", from which we derive the expression, "to peter out". The same signal is still used in Auction Bridge to show that the player can trump or win the third round of a suit. "Pembridge", famous as the author of Whist; or Bumblepuppy, prophesied that this convention would prove to be the forerunner of a mass of signals between partners that would finally kill the game.

Before Hoyle's time, Quadrille was the fashionable game, but Whist gradually superseded it among "ladies of quality" and became so much the rage that in 1790 we find card tables were placed in the boxes at the opera. At first, the game was ten points up, counting honours, and a code of laws for the game was drawn up in 1760, which remained until one eventful evening in 1864 when a certain Lord Peterborough, who was a heavy loser, asked that the game points be cut in half, so as to give him a chance to recoup.

THIS game soon became known, and was tried in many of the leading clubs under the name of "Short Whist", five points up instead of ten,with the result that it soon entirely replaced the older form. When America took up Whist the honours were eliminated, but the game was advanced to seven points, as it seemed absurd to be able to win more tricks in play than could, be scored.

In 1890 Duplicate Whist was introduced, and the first Congress of the American Whist League was held at Milwaukee in 1891. The invention of suitable apparatus for carrying the cards and keeping the four hands separate gave this game a great impetus, and it was all the rage until in 1897 Bridge (not Auction) gradually took its place.

In 1903, Auction Bridge was invented in one of the hill stations of the British Civil Service in India, as a game for three players who could not get a fourth for Bridge. Then the Bath Club in London tried it out for four players and liked it. The game was first introduced to America in 1906 in the supplement to Foster's Complete Bridge, but it did not become popular anywhere until the Portland Club in London took it up in 1908, and by 1910 the game had supplanted Bridge as completely as Bridge had superseded Duplicate Whist. Since 1910 the only changes in the game have been in the values of the suits, the scoring of honours, and the rules covering irregularities in the play.

Continued on page 104

Continued from page 86

PROBLEM LXXXV

OTHER CARD GAMES

During the last 150 years quite a number of games belonging to the Whist family have come and gone, notably Boston and Solo Whist.

Poker, by some still regarded as the national game of America, came to this country by way of New Orleans toward the end of the 18th century.

The only game resembling Poker that was played here 150 years ago was the English game of Brag, and it is interesting to note that the cards which were then indicated as braggers were simply "deuces wild".

At first, however, Poker was played with only twenty cards, all of which were dealt out to four players, and it was not until about 1830 that the game was played with the full pack.

This game, like all other favourites, has undergone a number of changes, designed to bring it into line with progressive ideas of what a card game should be. The draw to improve the hand was introduced shortly before the Civil War, and jack-pots were invented about 1870 to put a crimp on the "safety players" who followed the advice of Richard A. Proctor, the astronomer, and never bet on a hand unless they had three of a kind or better. Shortly after this straights were introduced, and so little was then known about the comparative value of the hands with regard to the probability of getting them that one always had to ask, when sitting down to play, whether straights or triplets were the better hand.

Close on the heels of the straight came the straight flush, so as to preclude any absolute certainty like four aces. This led to a number of stories about card manipulators dealing each of four men in the game a royal straight flush, and watching them bet everything they had on them. In later years, in order to nullify still further the mathematical knowledge of the experts, the stripped pack and deuces wild were added to the jackpot, until finally we seem to have forgotten all about the original highly scientific game and are now playing all Jacks, or Stud, with its cousin Peek Poker, both of which are quite recent additions to the poker family. The next step will be for some mathematical genius to reduce Stud Poker to a science.

One of the oldest of all card games is Cribbage, which has the distinction of never having been improved upon or changed in more than 150 years. Piquet is another old game, but has been made over in several details. A game that was very popular, especially in Great Britain, 150 years ago, was Maw, which was fashionable as far back as the time of James I, and a variety of it is still played in Ireland under the name of Spoil Five.

It is from this game that many suppose we got the once immensely popular game of Euchre. Although Spoil Five is played with the full pack, in both games the jacks outrank the other high cards in trumps. The deal is the same, five cards to each player, and the object is the same; to prevent any player from winning three tricks; that is, to "euchre" him. All efforts to discover the origin or meaning of the word "euchre" have failed, and there is nothing to show how the transition from the older games of Maw and Spoil Five to the modern game of Euchre came about.

Pinochle, another very popular game in America today, is descended from a game that was played 150 years ago called Marriage, and sometimes Matrimony, Cinq-cents, and Brusquembille, from which latter game we get the term "brisques" for the aces and tens in both Pinochle and Bezique. Bezique suddenly became very popular in England about 1869, but later died out. From being a game for two persons, drawing from the stock after each trick, Pinochle has gradually passed through an intermediate stage, in which it was a partnership game for four players, into its present form, which is a bidding game for three persons, with the surplus cards at the end of the deal left on the table for a "widow", to be taken by the highest bidder, who plays against the two others. This is almost as great a departure from the original game as Auction Bridge is from Whist.

DICE GAMES

A game that was once universally played by the nobility and gentry in England, and by . men of wealth and position in America 150 years ago, has now descended to the depths, and is the ruling passion of the coloured race and the chief standby of the blackleg. This game was Hazard, now familiarly known as Craps. Some of the most sensational gambling stories that have come down to us from the eighteenth century are about fortunes won and lost at Hazard. Our Poker stories of games on the Mississippi are as nothing when compared to them.

Continued on page 113

(Continued from page 104)

Such games as Chess, Checkers, and Backgammon are perennials, and have changed in nothing but the skill of the players during the past 150 years, except the conditions for championship play with regard to the openings in Chess and Checkers. The only noticeable changes in the implements are that we now' have wooden men, instead of the marvelously carved ivory pieces that were the fashion 150 years ago.

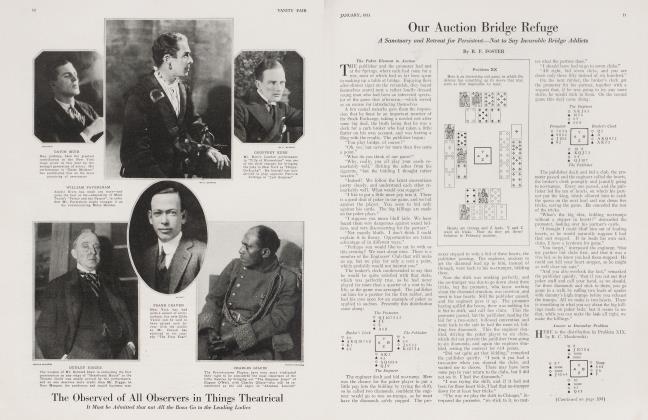

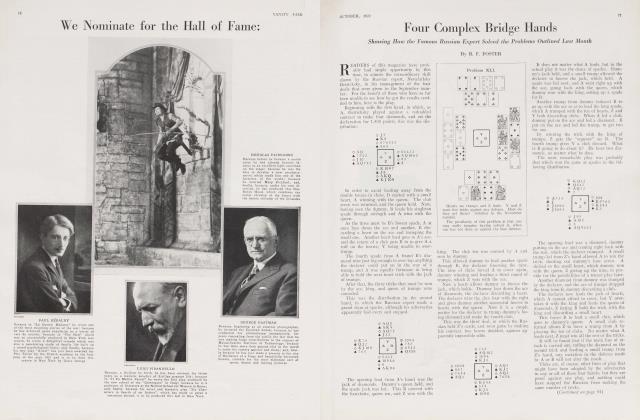

ANSWER TO THE JUNE BRIDGE PROBLEM

This was the distribution in Problem LXXXIV:

There are no trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want six tricks. This is how they get them:

Z leads the nine of diamonds, on which Y plays the queen. B ducks. As B refuses to win the first trick, Y leads the spade ace, upon which Z discards a small diamond. Y then leads the club, which Z wins and leads another winning club, Y discarding a red suit. As B cannot afford to discard a red suit, he sheds a spade. Z thereupon leads the smaller heart, which A wins and gives Y two spade tricks.

If B wins the first trick with the ace of diamonds, and leads a club, Z makes two clubs, Y discarding a spade. Z then leads the seven of diamonds, putting Y in. Y makes the ace of spades, Z shedding a small heart. Now' Z gets back on the heart to make the diamond. This show's the object of leading the interior diamond at the start.

If B wins the first trick and leads a spade, Y makes the ace and Z makes every other trick. If B returns the diamond, Y wins with the eight, makes the spade, and Z makes the rest. If B returns the heart, Z wins it, leads the small diamond and discards the small heart on Y's spade ace. Then Z makes the rest of the tricks.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now