Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowOur Auction Bridge Refuge

A Sanctuary and Retreat for Persistent—Not to Say Incurable Bridge Addicts

R. F. FOSTER

The Poker Element in Auction

THE publisher and the promoter had met at the Springs, where each had come for a rest, most of which had so far been spent in making up a table at bridge. Enjoying their after-dinner cigar on the verandah, they found themselves seated next a rather loudly dressed young man who had been an interested spectator of the game that afternoon,—which served as an excuse for introducing themselves

A few casual remarks gave them the impression that he must be an important member of the Stock Exchange, taking a needed rest after some big deal, the truth being that he was a clerk for a curb broker who had taken a little flutter on his own account, and was having a fling with the results. The publisher began:

"You play bridge, of course?"

"Oh, yes; but never for more than five cents a point."

"What do you think of our game?"

"Why, really, you all play your cards remarkably well," flicking the ashes from his cigarette, "but the bidding I thought rather wooden."

"Indeed! We follow the latest conventions pretty closely, and understand each other remarkably well. What would you suggest?"

"I like to put a little more pep into it. There is a good deal of poker in our game, and we bid against the player. You seem to bid only against his cards. The big killings are made on the poker plays."

"I suppose you mean bluff bids. We have found them very dangerous against sound bidders, and very disconcerting for the partner."

"Not exactly bluffs. I don't think I could explain it in theory. Opportunities are taken advantage of in different ways."

"Perhaps you would like to cut in with us this evening? We start about nine. There is a member of the Engineers' Club that will make us up, but we play for only a cent a point, which probably would not interest you."

The broker's clerk condescended to say that he would be quite satisfied with that stake, which was perfectly true, as he had never played for more than a quarter of a cent in his life, so the game was arranged. The publisher cut him for a partner for the first rubber, -and had his eyes open foran example of poker as applied to auction. Presently this distribution came along:

The engineer dealt and bid no-trump. Here was the chance for the poker player to put a little pep into the bidding by trying the shift, so he called two diamonds, confident the engineer would go to two no-trumps, as he must have the diamonds safely stopped. The promoter stepped in with a bid of three hearts, the publisher passing. The engineer, anxious to get the diamond lead up to him, instead of through, went back to his no-trumper, bidding three.

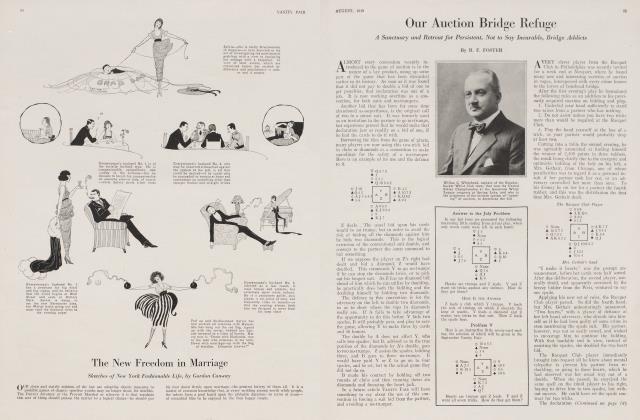

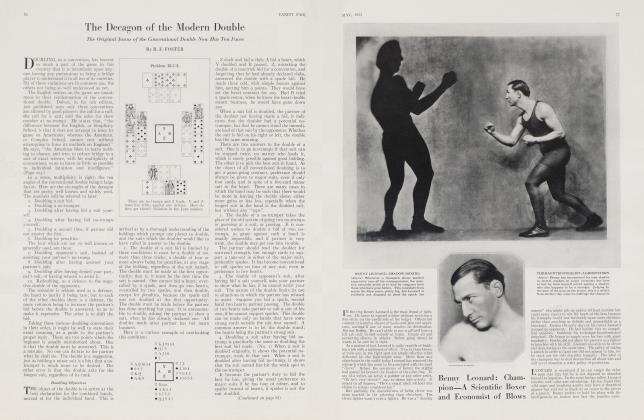

Problem XX

Here is an interesting end game, in which the defence has something up its sleeve that may seem at first impossible to meet.

Hearts are trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want six tricks. How do they get them? Solution in February number.

Now the shift was working perfectly, and the no-trumper was due to go down about three tricks, but the promoter, who knew nothing about the diamond situation, was insistent, and went to four hearts. Still the publisher passed, and the engineer gave it up. The promoter having spilled the beans, there was nothing for it but to shift, and call five clubs. This the promoter passed, but the publisher, reading the bid for a two-suiter, followed convention and went back to the suit he had the more of, bidding five diamonds. This the engineer doubled, driving the poker player to six clubs, which did not prevent the publisher from going to six diamonds, and again the engineer doubled, setting the contract for 614 points.

"Did not quite get that bidding," remarked the publisher' quietly. "I took it you had a two-suiter when you showed the clubs, and wanted me to choose. There may have been some pep in your return to the clubs, but I did not see it. I had five diamonds."

"I was trying the shift, and if it had not been for those heart bids, I had that no-trumper down for at least four tricks."

"The way we play the shift in Chicago," interposed the promoter, "we stick to it, no matter what the partner does."

"I should have had to go to seven clubs."

"All right, bid seven clubs, and you are down only three fifty instead of six hundred."

On the next rubber, the broker's clerk got the promoter for his partner, together with a request that, if he was going to try any more shifts, he would stick to them. On the second game this deal came along:

The publisher dealt and bid a club, the promoter passed and the engineer called the hearts, the broker's clerk promptly and jauntily going to no-trumps. Every one passed, and the publisher led the ten of hearts, on which his partner put the king, which allowed him to catch the queen on the next lead and run down five tricks, saving the game. He conceded the rest of the tricks.

"What's the big idea, bidding no-trumps without a stopper in hearts?" demanded the promoter, looking over his partner's cards.

"I thought I could bluff him out of leading hearts, as he would naturally suppose I had that suit stopped. If he leads his own suit, clubs, I have a laydown for game."

"You forget," interposed the engineer, "that my partner bid clubs first, and that it was a free bid, so he knew you had them stopped. He could not kill your heart stopper, so he might as well clear my suit."

"And you also overlook the fact," remarked the publisher quietly, "that if you cut out that poker stuff and call your hand, as we should, for three diamonds and stick to them, you go game in a walk by ruffing two leads of spades with dummy's high, trumps before you exhaust the trumps. All we make is two hearts. There is something in what you say about the big killings made on poker bids; but it seems to me that, while you can make the bids all right, we make the killings."

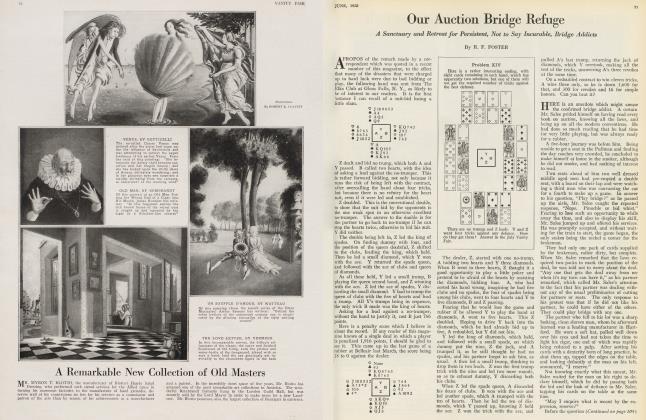

Answer to December Problem

HERE is the distribution in Problem XIX, by R. C. Mankowski:

Continued on page 104

Continued from page 71

Hearts are trumps, and Z leads. Y and Z want four tricks. This is how they get them:

Z leads the eight of diamonds. A's best defence is to trump and lead the trump, but this forces his partner to a discard, in which he has three choices. If B discards a club, Z will win the trump trick and lead the spade queen. Then he will throw B into the lead with the small diamond.

If B discards a diamond on A's trump lead, Z wins the trump and leads a small spade, instead of the queen. If A passes up this trick, B wins it with the seven, and loses all his clubs. If A covers the spade five with the ten, Z holds tenace over him for Ae last two tricks.

If B discards the spade on A's trump lead, Z leads the diamond and again

Y makes three tricks in clubs. If, instead of the trump, A leads a small spade at the second trick, Z wins it; but if A leads one of his high spades,

Y must trump it.

A small diamond opening will not solve,—as A trumps it, B throws in the jack and discards the spade on the trump lead.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now