Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAre Children People?

A Child's Thoughts on the Age-Old Feud Between Children and Grown-Ups

ELIZABETH BENSON

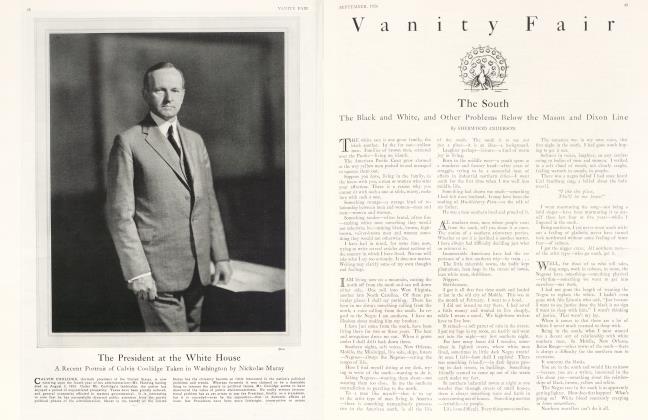

EDITOR'S NOTE:—Elizabeth Benson, the author of this article, A.re Children People?, is only twelve years of age, the youngest of the contributors to Vanity Fair. She established a world's record in the Binet-Simon Intelligence Test by scoring 214 + , the highest intelligence quotient ever recorded. By this and other tests, Elizabeth was rated (at the age of eight), as a "superior adult". By another test —the Miller Mental Ability Test—at the same age— she qualified to be a teacher in the high-schools of Los Angeles. Incidentally, she will enter Bryn Mawr this autumn. Her precocity is so marked that critics have claimed that her literary work could not be genuine. A jury consisting of Owen Johnson, the novelist. Charles Hanson Towne, Editor of Harper's Bazar and Guy Lowell, the well-known architect, recently made tests of Elizabeth's ability at impromptu literary composition in the offices of Vanity Fair. The jury's findings, after reading her essays on haphazard themes, suggested by themselves, were such as to bear out the conviction of the Editors of Vanity Fair, that Elizabeth Benson is an unquestionably authentic genius.

ARE children peopler Real people—not "kiddies", or "little folks" or "little ones", or what have you, in the way of patronizing tags for us human beings who arc not yet old enough to be accorded the sacred privileges of grown-ups?

Do you think we arc people? You say "Yes!" very loudly, all of you, but I don't believe you. I don't believe there is one adult in a hundred or a thousand, who really thinks of children as people—real persons, with individuality; with rights to opinions and to self-expression.

When I was five years old I entered school. Adults for me, up to that time, had been represented almost entirely by my mother, with whom I lived, the two of us alone and completely satisfied with each other. I didn't know, before I started school, that she was quite different from other parents; that I had always been treated a little differently from other children.

But I soon found out.

Teachers, other children's mothers and fathers; in fact almost all the adults with whom I came in contact, treated me—along with the other little children with whom I went to school—as if I were anything but a thinking human being.

I soon found out that if I expressed an opinion frankly—and I remember that I had decided opinions, even at the age of five, for Mother had insisted that I think for myself —I was called "forward" oi "impertinent". If I shut up like a clam, after a rebuff for being myself, my privacy was torn at by prying fingers; with some such patronizing and criticizing remark as "Cat's got her tongue!"

It was at the age of five that I began to dread meeting grown-ups, for, almost invariably, their first words were something as follows:

"My! What a fat little girl! What do you feed her on? She's very fair, isn't she? Docs she take after her father? Not exactly pretty, but she looks very bright. Come and give me a kiss, honey. I'm sure we shall be friends!"

And how I squirmed then, and how I still squirm! For I am still not considered a person, for I am only twelve. Not until I'm eighteen will I be admitted to the mystic shrine of grown-ups, where people treat each other with tact and courtesy.

Even when I was much younger than I am now, 1 used to have an impish desire to strike back at our visitor, to turn to Mother and say something as frame and unmindful of sensitive feelings as the visitor had said about me:

"How thin and wrinkled she is, Mother! I wonder if she's starving herself to keep fashionably thin? It's a wonder she doesn't get a facial. And what a horrid shade of henna she uses on her hair! But she has pretty eyes, hasn't she?" Then, turning to the lady, say to her in her own manner, "But I think you are very nice, in spite of your faults, and I am sure we are going to be great friends."

Do you think we should be friends after that? Hardly. But she probably would sweep out of the house in a fit of indignation after speaking a few well-chosen words on the subject of rude children in general, and rude me in particular.

I am sure that the adults who, on meeting children, discuss them as if they were pet dogs or animated dolls, do not mean to be discourteous or unkind. They have so far forgotten their own childhood and its humiliations that they haven't the faintest conception of the antagonism which is aroused in a child's breast when he hears himself discussed, criticized, analyzed and tagged, as if he had no emotions, no heart, no net-work of shivering nerves reaching to the remotest corners of his youthful being.

But it was not only the grown-ups who surprised and shocked me when I first went out into the world, at the age of five. The children, too, watched me furtively, sensed something different about me. Not that I was clever or anything like that, but that I admired my mother and enjoyed her society. You think that's funny? But don't you remember, when you were a child, that you belonged to an unnamed, secret society, made up of all the children you knew, whose purpose was to outwit parents, to hide all their true feelings and opinions from them?

GROWN-UPS, to us children, fall into three enemy classes: parents (and other relatives); teachers; and meddlers who haven't any right to boss us, but who try to do so anyway. In the last group come all the adults whom children arc forced to meet, and who talk down to us in a manner much like this:

"And how old are you, little girl? Seven? My, what a big little girl! Almost a lady now, aren't you? And do you like school? Do you love your teachers? I'm sure you're a good little girl. What do you like to do—play or help Mother around the house? What are you going to be when you're a big, big girl?"

Now, I ask you! What can you expect from a child when you talk to it like that? Do we unfold our minds and let our personality blossom under such a barrage of banal questions? Hardly! Of course we feel sorry for our mothers, who sit watching us and hoping that we'll say at least one bright, original thing, but we really can't do a thing about it. Mothers just have to suffer, if they will have friends who talk to children as if they were morons.

There is a variant of this type of adult visitor, who says vivaciously to the child's mother: "I just love children! Children and animals! Why, cats and dogs follow me on the street! And children—why, all the dear little kiddies in my neighbourhood just swarm to my place! Come here, darling! What a beautiful child!" (And the child knows she's lying!) "Wouldn't you just love to come over to my nice big house and play with my kittycats and pick my pretty posies and cat my lovely, lovely ginger cookies, and—" (voice lowered to a seductive whisper here)—"plav with the precious dollie that I had when I was a teeny, tinsy little girl, just like you? Wouldn't we have fun! And you can call me Aunty Baker! There! Won't that be nice!"

(Continued on page 106)

(Continued from page 60)

Yes, it will not!

Of course children do have friends among grown-ups, I have scads of them myself—real people, who treat me as if I were a friend, a person, an individuality. But I'm talking now of the great majority of grown-ups, not of the dear, charming exceptions who have made my life so wonderful. Pm sure my mother's attitude toward me has coloured the attitude of everyone who has ever visited us. She's as frank and friendly and casual with me as if I were the same age as she, or—which is more nearly the case— as if she were the same age as I.

If children are people, they should be given the three great gifts which make life for grown-ups so pleasant: namely, courtesy, justice and a tolerant understanding.

I've talked a lot about courtesy, because it seems to me that the most distressing thing about being a child is that adults have no true conception of courtesy—from the child's viewpoint. But there are graver wrongs that children nurse against parents and teachers and the world of grownups in general.

Is ordinary justice rendered to children r Grown-ups will answer that they protect children with childlabour laws, compulsory education, court rulings that compel fathers to support their children. They will also point with pride to the fact that, in this generation particularly, children get a "square deal"; that parents strive to give them the material comforts—the best of food, sanitary homes and good clothing. I grant all these evidences of justice for children. But I'm thinking of justice in a more personal sense, as between parents and children in every-day matters.

Take the matter of punishment, for instance. Even the best of parents are tyrants, sole arbiters of our fate, a court of justice—or often injustice —in which the father or mother is the judge and the jury and the prosecuting attorney. There is no attorney for the defense. The defendant is seldom allowed to take the stand in his own defense. He is arrested and taken to the whipping post, where he is punished before he knows what it is all about. Many parents punish first, then hold court later, if at all.

"But what did I do, Mama?" Johnny begs, between sobs.

"You know good and well what you did! I don't want to hear another word out of you! And stop that howling! The neighbors will think I'm killing you! Ask me what you did! You know you tracked mud all over my fresh-scrubbed kitchen! You know you went into the ice box and ate up every bit of that chocolate cake I was saving for dinner! There! (swish!) And there! That'll teach you to—"

But what's the use of goitfg on? Every child knows the story and every parent—or almost every one—will recognize the scene and he able to furnish the climax to it. Sometimes it develops—too late, from the child's viewpoint—that it wasn't Johnny at all who tracked up the kitchen and ate up the cake, but his brother Sammy, who (because Mama's anger has been expended in whipping Johnny) is let off with a scolding. And does Mama apologize to Johnny or try to soothe his wounded spirit, which is smarting more than his flesh? She does not! She may feel sorry and guilty, inside, but she tosses hothead and says to herself: "Oh, well! He's probably done something just as bad, or worse, that I don't know about! And I didn't spank him last week when I said I would."

Justice? I almost believe "there ain't no such animal" in the average home that is "blessed with children". Judging by the way some parents lord it over their children, you'd think the saying ought to go, "cursed with child ren".

If, smarting at an injustice, Johnny turns on his mother and says, "It ain't fair! You haven't any right to beat me before you know whether I did anything wrong or not!",, his mother is horrified; stunned at such impertinence. Then she bursts into tears and tells him that he ought to he ashamed of himself, talking to his mother like that; he doesn't appreciate her and all her sacrifices for him—his lovely home, his doting mother, his wonderful school, his brand-new suit which she really couldn't afford to get for him, all the luxuries which she didn't have when she was a child. She cries and cries and makes Johnny feel like a dog, until he cries too, and tells her that he didn't mean it, and that she's the grandest mother in the world.

But Johnny doesn't forget.

This is an extreme example of injustice, but it is a type that is found in some degree in every family. My mother is frequently unjust, for she is quick to anger. But never, in all the years that we have lived together, has she been unjust to me in this wav without acknowledging her error, and asking me to forgive her. And she never makes me feel hopelessly dependent by reminding me of all the wonderful things she does for me, as do nearly all the mothers and fathers of the other children I know. Another tlung: she has never broken a promise to me in her life. Broken promises cause more unhappiness among children than adults ever dream of. Parents make promises too lightly—"If you'll do this or that, I'll take you to the movies," or, "You can spend Saturday with the Browns in the country". Then the most trivial excuse serves most parents for breaking these lightly given promises that the children have taken so seriously.

It may be a broken promise, or an undeserved punishment, followed by no apology or admission of error on the part of the parent, that sows the first seeds of distrust and dislike in the heart of a child. These seeds may bear the hitter fruit of actual hatred or open rebellion when the child is old enough to make his own way in the world. In the meantime, the unjust parent may wonder why his son doesn't confide in him, why he would rather be anywhere else than at home, and why lie so resents his father's attempts to participate in any of his sports, pleasures or excursions.

(Continued on fage 108)

(Continued from page 106)

Tolerant understanding—the third major prerogative of a child, if he is really a person—is of course a result of justice and courtesy. It cannot exist without their having paved the way. Since justice and courtesy are rarely found in any great degree in the relationship between adults and children, what wonder that so little understanding exists between the two? How many adults show any tolerance for, or sympathetic understanding of, the myriad make-believes and gossamer fancies that float about in the mind of a child and sometimes find their way into awkward, fumbling words? Parents who believe themselves kindly and good arc too prone to label these childish expressions of make-believe as nonsense, and to send the child off on some practical errand when he tries to explain what is seething inside his imaginative mind. Or else they call it lying and punish the bewildered and terrified child. Have adults completely forgotten that children often live in a world of make-believe, constructed as a place of retirement from the realities of misunderstood childhood? The cobweb fancies of this world of refuge are as real as school and parents and home-life. It is a great compliment to an adult—parent or teacher or outsider—when a child lifts the veil and reveals some of these delicate fancies of his. If the adult laughs or scoffs at them, the sensitive soul of the child may close up like a pitcher plant and remain closed for years.

On the more practical side, adults show just as little tolerance for the small miseries that children suffer. When Mary goes shopping with her mother and timidly begs for a broadbrimmed hat, trimmed in just such a way—the mode of the moment in what Mary deems the most desirable circle of school societ)—her mother has not the slightest conception of the agony that is Mary's when a plain, serviceable, narrow-brimmed hat is forced on her drooping head, with the words: "You'd look a sight in any broad-brimmed hat with that thin face! Now, I don't want to hear another word out of you! Mother knows best!" If Mary is sensitive— and where is there a child who isn't—• she hates the new hat with a venomous hatred and in her heart there burns a dull resentment against her mother. Doesn't her mother know that it's just as hard on Mary to wear an unfashionable, serviceable hat as it would be on Mary's mother? Those are the times when Mary sulks, won't eat, wishes she were dead, and pictures her mother being sorry when it's too late.

Adults laugh at the tragedies of childhood, and make family jokes of them, with the best intentions in the world. But, to the suffering child, there is little humour in such jokes.

Many mothers say with pride: "My children have everything in the world they want. Why, when I was a child, I was tickled to death to get two new dresses a year, while Mary here has a dozen. And, besides, she has fifty cents a week for an allowance. Of course I try to make her save it, for I do think every child should learn to save."

How many heart-aches arc twined around that fifty cents a week that Mary gets—theoretically! There are a myriad little social distinctions in any set of people, and the "society" of childhood has rules as important and as complex as those of adult society. There are circles within circles, in school society, and a girl can feel social ostracism as keenly as her mother can. If she does not "treat" the crowd, when her turn comes, she is cruelly but perhaps justly edged out of the inner circle. If she does not invite them to her house for parties, if she doesn't entertain them in accordance with their rigid standards she may be dropped. Her mother would laugh at the idea if her daughter told her that she had been ostracized socially. As if children had "society"! The idea! Why, society is reserved and patented for adults! And, just because many a mother does not understand these things, and laughs at such distinctions among children, many a little girl lives a lonely, unhappy life.

Why can't she tell her mother all about it, you wonder? Every so often beautiful articles in women's magazines remind mothers that they must confide in their children and invite their confidence in return. Maybe this particular little outcast from the inner circle of school society has been taken upon her mother's lap half a dozen times in her life and told:

"Now, darling, Mother wants you to feel free to tell her everything— just anything and everything! You, will, won't you, darling? And Mother will tell you secrets, too!"

But "darling" isn't fooled. She has tried that confiding game before and it hasn't worked so well. If rhe confides something precious, out of her innermost heart, Mother may not understand, may smile involuntarilv, even laugh; or, if she does not approve of the pearl of confidence that "darling" has brought from her mental treasure-chest, she may be gently scolded by a shocked, hurt mother.

Do you remember Ernest's experiences in this respect with his addlepated, sentimental mother, in Samuel Butler's The Way of AIL Flesh? Ernest quickly found that his mother was simply laying traps for him; that, when she had learned all that she could learn from him, she used her information against him—and the others concerned in his confidences —with a ruthless cruelty, masquerading in the guise of maternal duty toward him, his father, his school, and society in general. Like Ernest, a child may be trapped once, twice, three times, but, eventually, he learns to shun the trap. And how few real confidences docs a child ever get from a mother or father who promises a fair exchange?

If I didn't have my own life with my mother, by which to contrast the usual relationship of parent and child, I should not dare to write so frankly of the small injustices and humiliations which keep childhood from being the halcyon period that adults think it is. If my mother were the average mother, I wouldn't dare show my face at home after this article comes out in print. But my own childhood has been happy, because the reverse of all that I have written has been true in my own case. From the time I was a baby, my mother has treated me as a person, a friend. She told me everything that happened in her busy days, made a real confidante of me, not in a condescending way, but as one friend to another. And, of course I told her everything that happened to me. I still do. I can't imagine having a secret from Mother, and I don't believe she has one from me, unless it is something that concerns someone else —a secret which she is not at liberty to divulge. When anything particularly exciting or depressing comes up during her day, she telephones me, and "gets it off her chest". I do the same. Her friends do not talk down to me; they do not snub me, or act as if they thought that children should be seen and not heard. I have been admitted to every sort of discussion that can possibly go on between interesting, creative people, since I was old enough to talk. I have been allowed to choose my own clothes, and, because I do not have to take it, I nearly always take Mother's advice in choosing my clothes, for she has better taste than I have. But she understands all about fads and schoolgirl society and such things. My allowance is mine to do with as I please, and no questions asked. I can make engagements with my friends, and be sure of being allowed to keep them, since the independence which has been allowed me all my life has made my judgment quite dependable. Mother recognizes my right to privacy; she does not open my mail or ask to see my letters after I have read them. Because she doesn't ask, I usually show her my letters, but if for some reason I don't, there is no resentment on her part. She shows me letters from our mutual friends, if she likes—and usually she does—but it would never occur to me to ask her to show me a letter which she had not given me to read.

(Continued on page 110)

(Continued from page 108)

For as many years as I can remember we have treated each other as two very close friends; with courtesy and tact. She never betrays my confidences, and does not use them against me. I believe it washer discovery, when I was a baby, that children are people, that was largely responsible for my rapid progress through school. Just because she did regard me as a person, she insisted that I must think for myself, take care of myself physically, and develop myself morally and spiritually from within.

In short, I had from infancy the freedom which adults have, and which children so bitterly envy them. And I do not think I have abused that freedom any more than the average right-thinking adult does.

As for grown-ups, I have a little private theory about them. I believe that their treatment of children is a sub-conscious effort to wreak vengeance on life for their own miseries and humiliations when they were children. I believe it all comes from the thought that children plant in their minds when they are smarting under injustices at the hands of grown-ups: "When Pm grown-up, I'll get even!"

The pity of it is that they get even with life by hurting their own children, just as they themselves were hurt so long ago.

As an observing spectator of both child and adult life, I've come to the conclusion, along with Christopher Morley, that there are no grown-ups, really. There are just children who are doing the things they wanted to do and couldn't do when they were children in point of years. The middle-aged man who capers about ridiculously and plays silly practical jokes on his friends is the grown-up version of the little boy who was repressed by the parents who didn't understand him. And yet he, in turn, will give his own son a whipping for doing exactly the sort of thing that he, as a grown man, is doing as a practical joke. It's a vicious circle, isn't it?

It isn't half so ridiculous as it is pathetic to see adults acting like children—or rather, as children would like to act if they could get away with it. And the spectacle of children playing "Mama and Papa" isn't nearly as funny as it is pathetic. If you grown-ups want to know what children really think of you, you should watch a couple of children playing a game of "Mama and Papa". The little girl, dressed in her mother's clothes, caricatures her mother with a preciseness of detail that is really startling. She whips her dolls with harshness for the most trivial of makebelieve offenses; she talks in mincing, affected tones; she whispers to the child playing "Papa" the most astonishing scandals about the neighbors; she complains of the servants in her mother's exact tones; she dolefully relates her numerous symptoms of ill health. She pats the doll that is portraying the role of visiting child, md patronizingly discusses its bad ind good points, telling it to be "a nice little girl and mind your mama".

The imitation is perfect. But the little girl who is giving such a realistic performance probably has no malice in her heart. She is merely anticipating the gorgeous time that is coming when she too will be grownup and can act just the way her mother does. If grown-ups do it it must be right, and the sooner she's old enough to do likewise, the happier she will be!

That's the reason why I wish fathers and mothers, and all other adults, would begin to think of children as people—so that the next generation of children will have a little more chance.

That vicious circle ought to be broken !

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now