Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowContract Auction Bridge

A Recent Popular Variation in Which One Must Bid Game in Order to Win Game

R. F. FOSTER

THE basic principle of contract bridge is that one cannot score below the line, toward game, anything beyond the value of the tricks bid, either at their normal value or doubled value, if doubled. All over this goes in the honor column as a bonus at 50 points a trick.

T here appears to be a reawakening of interest in this form of auction bridge, which would have been much more popular in this country than it is today had it not been turned down by the framers of the laws five years ago, when it was first introduced. The variation is a purely American invention, but so far without honour in its own country, although it has a large following in Europe.

The reasons given for refusing to legislate for it in our present code of laws was that "it would almost legislate the poor bidder out of the game." This assumes, apparently, that the poor bidder would always be opposed by experts, but very few rubbers are made up that way, or the regular game would be quite enough to legislate poor bidders out of the running. As a rule, people prefer to play with their equals in any game. The cracks like to make up a table where they can get good bridge, instead of having poor bidders for either partners or adversaries.

The authorities are not afraid to legislate liberally for duplicate, in which the poorest bidders have to play against the experts, as they are all playing the same hands.

Each of the three varieties of the game: the rubber game, duplicate, and contract, has its distinctive feature. In the rubber game you bid what you think best and make what you can. It all counts. If you bid one and make five you score five. If you arc 18 up and make two odd, you win the game. In duplicate you cannot win the game unless you make 30 or more points on one deal. In both games you score honors as held. In contract you cannot win the game unless you have bid enough to win it, cither from love or with a partial score, and you must have at least four honors in one hand to score them.

In both the rubber game and duplicate, success depends on arriving at the best bid for the combined hands, so as to win game or save game. In contract, success depends on bidding just enough to win the game if you think you can make it, but no more. In the rubber game partial scores arc worthless ten times out of twelve. In duplicate they are worth nothing. In contract they arc very valuable as stepping stones to safe bids on the next deal.

CONTRACT AS AN EDUCATOR

CONTRACT is the best possible educator in what Americans call team bidding, as success depends so much on the partners' abilitv to gauge each other's hands to the limit of their possibilities and to bid it when necessary, whether their adversaries offer any opposition or not. In the rubber game you bid a spade and second hand passes. Your partner is satisfied and you play the hand at spades. This will not do at contract. If you want to win the game you will have to get the bid up to four spades between you, unless you have a partial score to start on.

On the other hand, if you do not think you can win the game, you can sit back and see if the other side can bid game, because you can never lose a game unless they bid enough to win it. This makes the defensive game a matter of nice judgement, and the prospect of penalties is often more tempting than the hope of game. Doubling, however, is a dangerous experiment at contract, unless you are prepared to double anything.

THE SCORING

THE tricks and honors have the same values as at auction, but there must be four honors in one hand to score anything for them. This is because the rubbers run to such large figures, averaging twice those at auction, that it is not worth while to bother with small honor scores.

As originally played, all tricks made over the contract went into the honor column at their normal value. The result was that after the contract was fulfilled, the play had no further interest, as a few points in the honor column were not worth wasting time on. This led to the present system of taking 5 0 points for all overtricks, 100 if doubled, or 200 if redoubled, regardless of the declaration, suit or no-trumps.

In order to curb the temptation to overbid the hands to keep the rubber alive, it was found necessary to place more severe penalties on reckless bidding than those at auction or duplicate. A player who fails on his contract by one trick loses 50 points to the honor column of his adversaries. For the second trick, he is charged 100, and for all over two, 200 each. Thus it costs 150 to go down two tricks; 3 50 to go down three tricks. These figures are doubled if the bid was doubled.

If a player bids two tricks in a major suit, and is doubled, he wins the game if he makes two, as his contract is to make two tricks at double value, which is enough to win the game. A player who can make three odd at no-trumps is very foolish to bid four unless compelled to do so by adverse bidding, as all over three, which is game, will count him 50 each as overtricks, instead of 10 only as tricks bid.

The usual scores hold for slams; 50 for little and 100 for big, but if a player is bold enough to bid a slam, and makes it, he scores 250 for little slam, and 500 for grand slam. Such bids come along about one or twice a year, but they arc interesting when made.

For winning a game, 100 points are added at once. For winning the rubber game, 3 00 arc added, so that a partnership winning the rubber in two straight games gets 400. If three games arc played, the rubber is worth only 300 to the winners.

The revoke penalty is to take two actual tricks from the side in error and give them to the other side, but tricks taken previous to the one in which the revoke occurs are not subject to this penalty, and if there are not two tricks to be taken, the side not in error must be content with one or none.. The scores are then made up as the tricks lie, just as if they had been won in play.

LONG RUBBERS, BIG SCORES

OWING to the number of partial scores made, the average number of games to a rubber is seven, instead of the five that is the rule at auction, and the average value of the rubber is about 780 points, instead of 380. This would suggest that if one is in the habit of playing penny points at auction, half a cent would be about right at contract. Good players average about two rubbers an hour.

The successful players seem to be the cautious bidders, who never speculate, and take no chances except when justified by the score, cr afraid of losing the game or rubber. With good players, about 70 per cent of the contracts undertaken succeed, and about a third of them arc no-trumpers. Two-thirds of them make a trick or two over the contract. In a record of 120 consecutive rubbers, 1,800 points was the largest winning on one rubber.

BIDDING TACTICS

When it comes to the principles of bidding, there seems to be a tendency to requiring greater strength, say at least a trick more, than would be considered a safe minimum at auction. Sporty or weak notrumpers are regarded as dangerous original calls, as the adversaries are liable to leave you in, where they would overcall a suit bid. Original bids of two are frequently used to show strength in two suits, so as to encourage the partner to assist, when he might not do so on a bid of one. He may even be able to bid high enough to reach game, if he can guess what the second suit is.

Continued on page 105

Continued from page 80

The most important thing to learn is not to be too anxious to make a game call on every hand, but to be satisfied to bid what the hands are clearly worth.

Z dealt and bid two hearts, the score being 18 to 0 against him. At a love score A would pass, as there is no hope of going game in a minor suit if Z is strong in two suits, both major, and unless Y increases the bid and they eventually get it up to four, they cannot win the game. But with 18 points up, and wanting only three tricks, A has no hesitation about bidding three diamonds.

Y knows his partner has something outside the hearts and goes to three. B passes, as that contract will not win the game. He does not help the diamonds, nor does he double the hearts, but waits for Z. Z took a chance and went to four hearts, so as to win game if possible. Now B doubles and they set the contract two tricks. A could have made three diamonds if left to play it.

One of the fine points of the game is to secure the contract as cheaply as possible when you know you cannot go game. If you can neither bid nor win tricks enough to reach game, all over your contract will be worth 50 points each.

ANSWER: DECEMBER PROBLEM

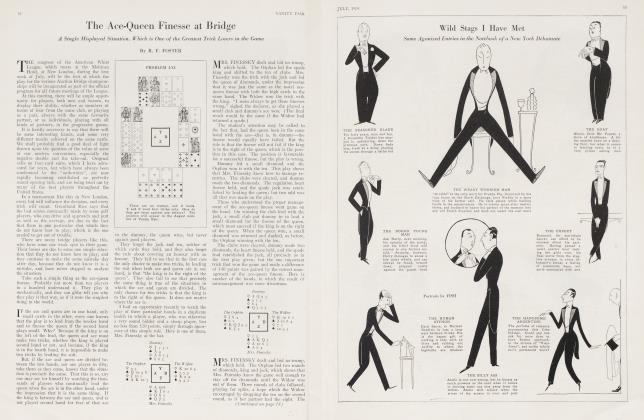

This was the distribution in Problem LXXVI11

Hearts are trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want six tricks. This is how they get them:

Z leads a spade. If A covers, Y wins and leads the ace of trumps followed by the small one. B discards a small club and a small diamond, to protect the spades. Z discards a club or a diamond, and A a diamond or a spade. Y leads the spade, putting Z in.

Z now leads the diamond queen. If A covers with the king the jack falls and the ten is good. Y discards instead of trumping, and discards again on A's diamond lead.

If A does not cover the spade on the first trick, the queen holds, and Z shifts to the queen of diamonds. If A covers, Y trumps and leads ace and another trump. On the first trump lead B will discard the small club, and must then let the jack of diamonds go, or Y makes the next trick with the deuce of clubs, forcing another discard. Z sheds the club; A a diamond. Y then leads the small spade, which A wins and loses two diamond tricks. A must keep the spade king or make the last trick with the nine of diamonds.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now