Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA Great Factory

Problems and Attitudes in Life and Industry Considered from a Workman's Angle

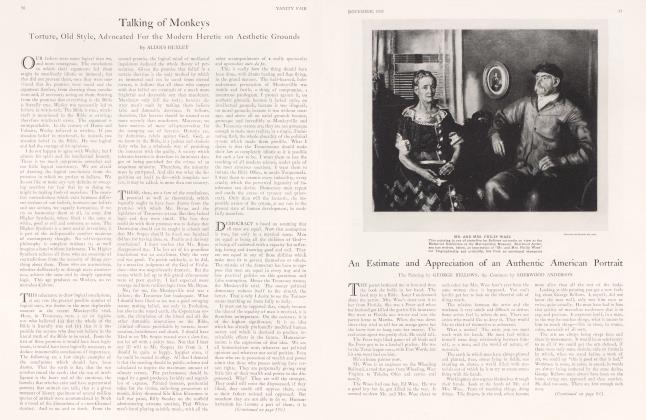

SHERWOOD ANDERSON

MANY men, living in one long house. Rows of small frame houses, all built alike, along the streets of the industrial suburb. Other streets just like it running in all directions. A great city of such streets off to the north. If you took a street car you got down into the business section of the city. Great department stores, big hotels, swell restaurants. Lordy, how many people in this world! How do they all manage to make a living? You could take another car up to the park and on up to where the swell houses were. In your own street—dust, dirt, crying children, toughs in the pool room at the corner. Up there gardens, flowers, green grass growing.

There were two women—sisters—who ran the long house. One of them had married— a fleshy young man who always went about in his shirt sleeves and had a cigar stuck in the corner of his mouth. He ran the pool room in the same street. Some of us went in there on Saturday afternoons or evenings. Harry and I did once or twice. It wasn't a very good place to go.

There were young men hanging about who never worked—better dressed than we were. Get into a game with one of them and, if you were sap enough to lay a bet, he stuck you every time. One of them stuck Harry for a whole week's pay. Harry said he had it coming to him. They were all pool sharks—the well-dressed, cigarette-smoking young men.

THE two sisters in that factory labourers' rooming house worked like mules. Harry and I hadn't much time to be sorry for any one except ourselves but we were sorry for them. They did the cooking in the house, swept and made the beds. It was a huge place—not too clean. Well, it wasn't clean at all. It was said the pool room keeper came home drunk sometimes and beat his woman. I never saw or heard anything of that.

The other sister. Well, you know how young labourers or factory hands talk. Their fancies linger over any woman they see. I was that way myself at that time. Harry may have been. He had a lot of natural reserve. A fellow named "Cal" told me he saw one of the sisters and a man named Slim Beal in a room together.

It was a lie. One day when I was ill she came into my room to make the bed. I could not help thinking of what Cal had said. When I looked at her the idea of her not being straight was absurd.

Trucks in the street outside, dust thick on the window panes. I sat by the open window and had in my hand a copy of George Borrow's Romany Rye. A lot of the other labourers in the factory used to call me "the professor".

The tall sister, with the bony hands and the tired sad-looking eyes, began to talk. Her checks grew a little red. She was embarrassed because she had got the impulse to talk and it was hard work for her. She told me about a younger brother who had died. It was evident he was the hope of the family. She said that the younger brother liked to draw pictures.

"I do, too," I said, "but I am not very successful. I suppose I'll just be a common workman all my life. I wish I could do something well."

SHE looked at me, sizing me up. "Of course," she said. It was evident she did not see anything in my looks to make her want to refute my statement. The brother, had he lived, would have been a genius. She knew it quite definitely. He could draw anything— a horse, a ship, a pig, just anything. Show him a picture in a newspaper or a magazine and the next day he would have it down in black and white, as natural as life.

The sister's eyes shone as she spoke of the dead brother. I tried to draw her out concerning her position in the house. "Why do you work here? I bet they don't pay you any too much."

My words frightened her and she went quickly away. It was the only talk we ever had together.

The factory where we worked was a big one. With the man at the next bench I got acquainted quickly. That was Harry. He was the only man there I did get to know well.

He did not belong to the factory or to factory life. Something was all wrong. How I knew I can't say. Harry had a certain air, walked across a room with a certain indefinable swagger. Later he lost most of his swagger.

Back of us both clung a memory of other places, other kinds of life—the life of fields, farms, orchards, small shops in small towns where the factories had not come yet, of nights on country roads under the moon, of rains and snows. "I'll walk out of this damn place when I get ready," I said to myself. I was strong of body. Work in fields is heavy, hard work and the pay is not much but there arc no brick walls closing you in. I was in the presence of something tremendous, powerful—but it hadn't got me yet. It hadn't got Harry—yet.

I SAID something to him one day at the noon hour. His eyes grew bright. We became friends.

He took a room next my own in the great barrack-like place kept by the two sisters. Most of my own thoughts of factory life and what it means to the men in factories, what it does to men, are really his. Later I made my getaway but he stuck, became a drifting factory hand going from city to city, from shop to shop. He may not have been as shrewd as I was. I saw him once, fifteen years later. He had been hurt in a factory and was dying. They were taking the best of care of him. He had, in some mysterious way, kept track of me and sent me word. His opinions of factories hadn't changed much. He died, I thought, rather handsomely.

He thought the industrial age, the age of factories, too big for human comprehension, disastrous to men, but did not put the blame on any one.

Let me return to our life together. We used to go in the early morning down a long dirty street to the factory. Outside everything barren and ugly. Inside everything clean and shining. This particular company had buiit most of the houses in the industrial suburb. The houses were all alike. There was no expression of individuality. Well, you can't have artists building factory towns, can you?

HARRY walked beside me, worked beside me, came home with me evenings. We talked—trying to find ourselves in our world.

On some evenings we walked out beyond the town, on country roads or along railroad tracks. This was in the winter and it was often bitter cold, with biting winds blowing. We were young enough not to mind. It did me good just then to be with a man as impersonal as Harry. A lot of labourers arc always flying off the handle, talking wild. You see I had to get factory life from the men's angle. I was one of them.

The factory was something—the walls well built, great light rooms. The factory stood for something very definite.

There was a row of shower baths where you could go and get clean after the day's work. Nothing lacking in physical comfort. The work was easy.

Something more than that—something splendid. Such vast quantities of goods made and very well made.

THE great factory in which we worked was an impersonal thing like something in Harry, who was to spend his life working in factories. The steady, even hum of vast machines—beauties many of them—so intricately made, doing such marvelous things. Click, click, click. Goods being made, carloads, trainloads, shiploads of goods. I could get a thrill any time, looking at the machines. They frightened me, too.

Harry was the son of a country doctor. He had left home because, in a quarrel, his father struck his mother with his fist. "I had to leave or kill him." He did not talk much about himself.

We were one in our admiration for the machinery and the organization of the great factory. Men had done it, the minds of men had done it. From the angle of production it was almost perfect. The sound of the machines sang in my dreams all night. They were powerful, persistent, accurate. They did not tire. Harry and I agreed often that men in general had little or no appreciation of what a marvelous thing the modern great factory had become.

It was far bigger than the men who owned it, who ran it, who worked in it. Were we afraid because it was bigger than the individual? We were. We were country-bred lads— individualists. My own individuality has always been the most bothersome thing in the world to me. Take it away and I am nothing. Solve all the problems of my life for me by industrialism, by standardization, and you leave me a dead man. I think I have always realized that. Nothing in the world could ever make me a socialist.

THERE were radicals enough about. They talked and we listened and on the whole thought them rather off the point.

Harry and I had both come from places where men still worked with simple, crude, rough tools. After he had left home Harry had worked as a farm hand. We had no illusions about labour—as labour. After listening to radical talk I remember Harry's saying, "These radicals are men who think that if they could change the form of government, the social scheme—if they could take ownership out of certain hands and place it in other hands —they would miraculously become good workmen." He thought that what men wanted was to be good workmen. I think so too.

Later, I remember, he somewhat revised that saying. "The reformer is a man who starts with a genuine passion for making life better for all men. The job is too big. A man has to save himself. The scheme the radical has fixed upon becomes in time the expression of his individuality. To give it up he must give up everything. He missed the point. The workman does not consciously call attention to himself. His work should do that. The difference is this—the radical is trying to change things—the workman to make things."

I have a notion that Harry did not get it all. There must be, somewhere back of every reformer, a sense of some divine order. It may be many of them are ready to surrender individuality for the common good. I am afraid I am not.

Workmen and artists are not primarily concerned with the fate of men. They are concerned with things, what they, as workmen, can do to things. I believe that, deep down in him, every man wants to be a workman more than he wants anything else. He wants it more than wealth, success, women, fame, honour.

Men want it as women want children. It's nature.

The great factory—modern industrialism— standardization—stand in the way. Well, what are you going to do about it? Industrialism, standardization have made the modern social scheme possible. They go together. You can't chuck facts. Without standardization you can't have the great factory—you can't have modern life.

You can't have your cake and eat it too.

YOU will understand that I am trying to speak of something huge and vast, to give as best I can, the feeling of two workmen regarding the great factory they worked in. Although for twenty years now I have not had one political thought, have no scheme for changing anything in the social structure, I am every day more keenly aware that my life is in no way what it would have been if great factories had not sprung up like mushrooms all over America in my time.

I am only saying here what the workman Harry and myself thought of the great factory while we worked together in it.

Admiring it, often overcome by a feeling of awe, admiring the men whose ingenuity had devised the specialization of work, the efficiency of it all—feeling that in bringing the comforts of life to men at a low cost in human labour, the great factory had come near selfjustification, we could not go with the men of another generation in thinking the machine could solve men's problems. Organization of men in some socialistic state scheme, to make efficiency more efficient, we thought would make things worse.

The great factory — standardization—all that frightened us. I fled from it. He stuck. Modern life has affected me as deeply, getting out, as it did him, staying in.

TO return to our talks on winter nights, walking often under factory walls. At night the dark factories seemed like prisons. They are prisons. Some men think life itself is a prison. We helped each other to a kind of acceptance—that is the reason we became friends. I dare say many of our thoughts were crude enough. I am not presuming to be very certain I have got far with the subject on which I am trying to write.. It is a rather large order.

I am only saying we were afraid of the great factory.

The shining wheels always flying, vast quantities of goods pouring out, lives of men made more comfortable everywhere, men employed, the power of the country growing, wealth being accumulated—in two workmen a feeling of fear. Not of wealth.

What of wealth? I would like to be wealthy

myself. Wealth means to me the opportunity to do as I please. It means the chance to work always at what interests me most.

The many, in spite of dirty streets, ugly houses—better off in every way than labourers ever were before industrialism came. The terror of sheer brute, heavy labour that few men nowadays know—lifted, at least partly, from the shoulders of mankind.

Realizing that to blame any one rich man or group of rich men for what evil the coming of the great factory has brought is foolishness, childishness.

Still buried deep in us the feeling of fear.

Of what? Two boys walking, asking themselves that question, asking each other.

Did they know of what they were afraid?

SOMETIMES I think I do now. I have the individualist's fear of mass production—fear of losing touch. I never walk past a great factory now without having that fear. I am a man of the west, an individualist. Selfabnegation is not my strong point.

It may be that I am speaking only from the artist's viewpoint but I do not believe it. The artist is the man whose whole life is centered on the problems of not losing touch. I believe that any man who is a workman has something of the artist in him. The man who is not a workman is not a man at all.

Fear of losing touch. With what?

Why, with wood, cloth, iron, stone, earth, sky. The line this pen makes on this paper as I write, the quality of the paper, the ink, with everything in nature my mind or body touches. My life is centered here. Life, to me, has always this universal quality. There is something the machine cannot do for me. When the machine makes my fingers useless it makes me useless. I am afraid of the impotency that comes with the losing of the workman impulse.

Delight in the hands, in what the hands do, what the fingers of the hands do to things in nature. Is all that over the workman's head because he cannot express it? I express it in words because I am a workman in words. It is my job to find words to express such hidden fears.

MAN'S inheritance—his primary inheritance—being taken from him perhaps by mass production, by the great factory, by inventions, by the machine.

The great factory then, for all its wonders, remains a threat to the individualist, the workman. I, an individual, must save, for myself, my own individual touch. The tendency of the factory, of industrialism, is inevitably to place the emphasis on production, rather than on the process of production. That tends to destroy the workman in me. If someone can show me that I am wrong I shall be glad. There are already a great many great factories. There will be more.

It may be that the age of the individual has passed or is passing. Men are always rising up to say that the day of the artist is gone. They have said it many times in the history of man. When the workman, the workman impulse, passes there will be no more artists. I do not want to live in such an age and, being an optimist, do not believe it will come.

It may be after all a matter of emphasis. Now the emphasis is all on production. It may come back to workmanship one of these days.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now