Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowInside Speaking Out

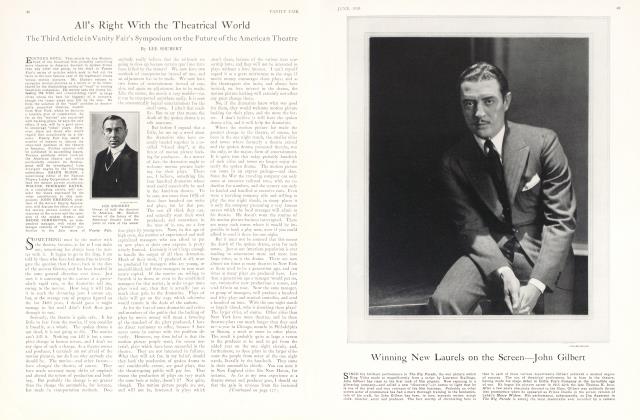

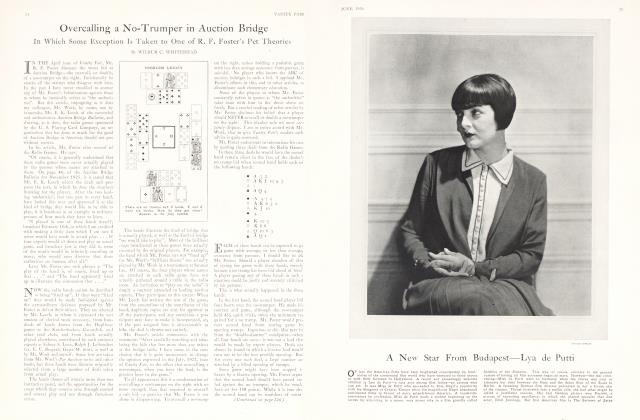

Revealing Further Secrets of Play Producing—The Out-of-Town Opening

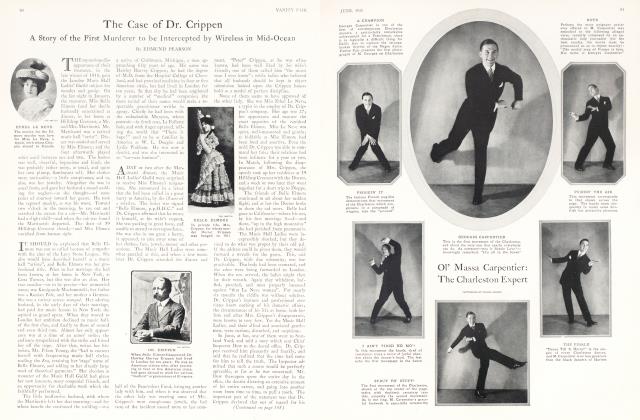

LESLIE HOWARD

SIXTH (AND PENULTIMATE) LECTURE

THOSE of my readers who were intelligent enough (or strong enough, as the case may be), to endure to the end of my last lecture, may possibly have wondered what on earth else there remains to be told about the production of Heart's Clouds, that wondrous drama. They will have conjectured something as follows, "What more can the fellow have to tell us about this play. Everything seems to have been thoroughly muddled up. The director, poor devil, has been told he has just one week in which to produce a sixteen scene tragedy, he has got an almost entirely brand new company, the manager has never so much as shown himself, being still in Florida, and to cap things, the star has now refused to play with the ingenue. The director cannot get rid of either, as the star has a legal hold on the play, while the ingenue has a hold (not quite so legal) on the manager. The play obviously cannot be done."

Well, of course, the play can and will be done—after a fashion. In the production of a play things generally proceed from good to bad, from bad to worse, from worse to hell, after which they recover somewhat—usually. Mr. Stilton, the director, solves the most immediate difficulty by sending the ingenue to sec her friend, the manager down in Miami, counting on her not being back much before the play opens. Meanwhile the stage manager reads her part.

Now I cannot deny that six days is not a great deal of time in which to prepare even a simple drama, and Mr. Stilton, feeling just as I do about it, exhorts his company not to expend a great amount of aesthetic finesse upon their roles, but to confine themselves to the simple memorising of their lines.

"Cut out the swell acting, folks," he says in his inimitable way, "and learn them verses. You won't have no books in your hands Monday night. You'll only have ya brains to fall back on. God help ya then."

I DON'T propose to go into the details of the somewhat hectic days that follow, but 1 will pause for a moment at the dress rehearsal, an interesting function which I feel the layman who is following these lectures should know something about. Though the dress rehearsal is often such in name only, that very name continues to inspire with terror all who take part in it. Heart's Clouds is scheduled to open in Stamford on the Monday night, and the company is called for dress rehearsal at a New York theatre at 9 a.m. on Saturday. This early start is necessary, inasmuch as there is a matinee performance scheduled in the theatre, but there is quite a panic among the company on being told of it. You see, 9 a.m. is almost an incredible hour to most actors, many not really believing in its existence at all. Some of the cast, having been unable to ascertain exactly when 9 a.m. actually is, go to Mr. Stilton and ask him if he doesn't mean 9 p.m. which is an hour they know something about. Finding they really have to be there at this fabulous hour, they resort to various means of assuring their arrival. Some stay up all night, some, having business friends, ask them to call them up, one sends himself a night letter, etc.

Looking a little worn out, they appear on the stage more or less at 9 a.m. all dressed and made up. They find a large force of stage hands busily banging nails into a huge piece of scenery which is lying on the floor of the stage. The company wait around for half an hour, and then, feeling they are rather in the way, go back to their dressing rooms. One hour later they are awakened from their fitful dozes by the stentorian voice of the stage manager yelling "Beginners, Act one please—on the stage quick." They tear downstairs nervously, and on arrival on the stage are surprised to find the same large force of stage hands still banging nails into apparently the same enormous piece of scenery, which has not moved from its prostrate position on the floor. This time they remain, and a long, long time later, are rewarded by seeing the stage hands raise the recumbent mass from the floor and attempt to push it into place. This they seem to find inordinately difficult, and finally, about noon, a voice from the darkened auditorium shouts, "What the hell's the matter," whereupon a rather nervous stage manager steps to the footlights and says, "I'm sorry, Mr. Stilton, but it doesn't fit."

"What doesn't fit, for the love of blank blank?"

"The set, Mr. Stilton, they made it too big. I guess it'll fit at Stamford all right."

"I guess it will too. If it don't, you'll fit in some other job. Let 'em rehearse without it."

The company, thereupon, hoping the other fifteen scenes fit better than this one does, play the first scene on the bare stage, and then retire to their dressing rooms to get ready for the second scene. They are told to hurry, and scramble into their clothes frantically in the space of a few minutes. After this they wait for another half hour, and finally at 1:30 p.m. the stage manager sends a message that the dress rehearsal will be postponed till tomorrow night, Sunday, at Stamford, at 8 o'clock sharp.

The next day, the entire cast travel down to Stamford, engage rooms at the only hotel, and at about seven o'clock those who are still in the hotel receive a message that the dress rehearsal has been postponed till 10 o'clock. The cast settle themselves down in the hotel lounge, some trying to remember their parts, and some trying to forget them. Eventually they drift along to the theatre, where a rumour is spreading that the manager, Mr. Samuels, has returned from Florida and is to be there tonight. This rather excites them, as, none of them having ever seen him, he has acquired a sort of mythical significance in their eyes. At 10 o'clock sharp they appear dressed on the stage, to find the setting for the first scene, with a persistence that is becoming monotonous, in its customary prone position on the floor. Over its recumbent frame a frightful row is in progress between the director, the stage manager, the assistant stage manager, the scenic artist, the stage carpenter, the property man, and various others concerned. It appears that the set, having been too big for the New York theatre, has turned out to be too small for the Stamford theatre. Mr. Stilton is speaking severely to the scenic artist.

"Will ya please tell me," he bellows in his righteous wrath, "if there's any blank blank theatre in the blank blank United States that the blank blank set will fit."

THE scenic artist quite irrelevantly replies that the set is not yet paid for, which doesn't improve matters, and the ensuing argument passes another hour pleasantly, at the end of which Mr. Stilton decides to cut out the first scene entirely, feeling, no doubt, that fifteen scenes are just as good to any play as sixteen. Concerning the rejected set, he informs the scenic artist that he (the scenic artist) knows exactly what he can do with it.

It now being eleven o'clock, the cast once more retire to get ready for the second scene, which is not so elaborate as the first, being merely a large piece of canvas with the railway station at Fresno painted somewhat idealistically, upon it. (The discarded set had purported to be a representation of the interior of a Pullman, car en route to Fresno.) At 11:30 the curtain is actually about to ring up when a telephone, message from New York announces that Mr. Samuels is just leaving for Stamford, and will, they hold the curtain an hour till his arrival.. On this news the star, Miss Florence Partridge, gets in her car and returns to the hotel, asking to be called when the manager arrives. The rest of the cast, having no cars and being in make-up, wait around patiently for another hour.

(Continued on page 90)

(Continued from page 62)

At a quarter to one a.m. another telephone message from New York bears the interesting news that Mr. Samuels after all has decided not to come to Stamford and will they go ahead without him. Mr. Stilton's observations on this information are absolutely indescribable, and they become positively apoplectic when, as the curtain is finally about to rise, it is discovered that the star is not present, no one having called her. Finally the assistant stage manager has to fetch her.

Eventually at 1:35 a.m. the curtain triumphantly rises, though Miss Partridge is neither in the best of form nor the best of tempers. However, five or six of the fifteen scenes are valiantly fought through, until suddenly, at ten minutes past four a.m. the lights all go out. As it is practically impossible to conduct a dress rehearsal in pitch dark, the director decides to call it a day (though to the cast it has seemed more like a month). Joyfully they all troop back to the hotel in the dawn, having nothing whatever to do but sleep till eleven o'clock, when they continue rehearsing till six or so, the curtain going up on the first public performance about eight.

Exactly at the published hour the curtain rises on Heart's Clouds, of which the title I forgot to mention has been changed at the last moment to The Earth is a Box. No one ever quite knows how the curtain goes up on the first night, but in spite of lack of scenery, lack of properties, lack of lines by the actors, and sometimes even lack of actors themselves, the curtain somehow rises at the scheduled hour and the show is somehow got through. So with Heart's—I mean The Earth is a Box.

The manager, I regret to say, has not even turned up for the first performance. I had explained previously that he thought the play pretty terrible in the first place, did not think it had a chance in the world, but was positive it would make a great motion picture which would be worth at least $50,000 to him. As the play's production progressed, his original impression was more than confirmed, and he decided to have as little to do with it as possible. However, just as he is sitting down to dinner on the opening night, Mr. Stilton calls him up from Stamford, saying they have a huge house and the first act has been received with cheers. In case he might have made a mistake, Mr. Samuels gets straight into his car and speeds to Stamford, arriving for the conclusion of the second act (or twelfth scene). As he enters the theatre, he hears a great burst of applause and. cheering as the curtain comes down. Quickly rushing back stage, he leadst on to the cheering audience the star, the author, the principal members of the cast (most of whom he has never met till now), and concludes by making a fine emotional speech, in which he declares that he had always had faith in this beautiful work of art, and although he did not and does not think it commercially valuable, still he is only too willing to lose money if by doing so he can give the public fine plays. He is greeted by an avalanche of applause which convinces him that, in addition to having produced a good moving picture for Gloria Swanson, he has also produced a profitable play. During the progress of the last act, he stands at the back of the theatre with his director, Mr. Stilton.

"You know, Dave," he observes, "I bin mistaken about this show. I didn't think it was woith a damn."

"I still think it's terrible," responds Mr. Stilton. "And what a cast. Christmas! All you can hear from here is the prompting. I don't know what's the matter with the audience."

The last act is now over and does not receive quite the ovation the previous ones did. This may be partly due to the fact that something always prevented it being reached in rehearsal, so that the stage manager's voice, vigorously prompting the cast, may have become monotonous to the spectators. The manager, however is satisfied.

"It's a cinch, Dave," he comments. "We'll take it on the road for a few weeks and fix it up, get that sap to rewrite it here and there, and it's good for a year in New York."

Then he returns to town, feeling he has done a good evening's work, even if he has missed his dinner.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now