Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHotel Côte d'Azur

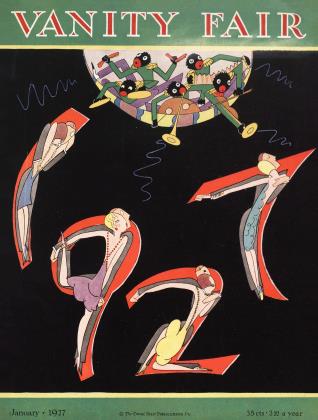

A Story in Which a Dingy Hotel Parlour Blooms Suddenly With Romance

THOMAS BURKE

AS I sat in the brown dusk of that parlour, the rain iell with impotent hisses upon the window-pane, and out of the stillness, which was not cjuite silence but rather a muflling of the world's pulse; out of this stillness into my mind stalked a company of crippled images. I thought of ex-soldiers selling matches. Of Oscar Wilde in convict uniform on Clapham Junction platform. Of Rosherville Gardens on its last night of life. Of street-organs playing old tunes on yellow afternoons in the bye-streets of Stepney. Of elderly pensioned clerks wandering listlessly in suburban parks. Of streets in South London that stretch to the direst hell that man can conceive —the something that does not end. Of people getting run over by 'buses on wet days. Of tired charwomen having their pockets picked of their week's wages. Of unloved women who lie late in bed reading novelettes.

It was that sort of room.

I was drawn into the place one October evening, when taking the Hungerford Bridge way, by steps and dark arches, to Waterloo. I had passed it many times before, but it had not, until that night, moved me to ask it a question, though I had seen it always as "wrong". Outside, it was like the rest of the dim and discreet "private hotels" that make silent solicitation round all the big railway centres; but it was marked from the others by its name— Hotel Cote d'Azur—and by an illuminated sign bearing that name and adding: "Lounge Open to All". Each time I had passed it 1 had carried, for the next fifty paces, pictures of the Mediterranean, and of E/.e and La Turbie and Cannes and Roquebrunc; sunshine and colour; things that made discord with the alleys of Lambeth and with that kind of private hotel.

HHHAT night, with the mist of October fillil ing the street, it seemed to be isolated; the central figure for whom the mist was made. Perhaps, 1 thought, as 1 approached it, perhaps it is different. Perhaps it really has nothing to do with its fellows, but does carry something of the Blue Coast of France. Perhaps one ought, seeing that its "Lounge is Open to All", to investigate and find out how these shabby imitations manage to live in the shadow of real hotels; and what sort of custom they catch when, within sight and within walking distance, are a dozen hotels proper. Surely, even guests temporarily coupled would want backgrounds less drab for their drab intercourse? And why did this place take that name and, among a group of similar places, alone open its Lounge to All?

I went in, and I found no answer to my questions. 1 found the open Lounge; took a swift look and smell at it; turned to run out, and collided with a forlorn, slip-slop chambermaid. Before 1 could gather my wits, after the collision, to the point of ordering myself out of the place, 1 had ordered from the spectre a drink. Having given the order, I had to stay; and 1 sat down in a parlour where, 1 felt, most company would be silent and all would be damned. The windows were closed. A faint glimmer of light came from one gas-iet with a torn incandescent mantle. The gas bubbled and gave the light the ague. There was a massive dinner-waggon, carrying nothing but a cloudy cruet. There were prints of The Stag at Bay and Dignity and Impudence. There was a writing-table with soiled blottingpad, encrusted pen and open ink-well—dry. The grate held a heap of black coals from which came a faint glow and an occasional thrust of flame. There were two cabinets let into the alcove by the fireplace; they might have been book-cases, but as they had blind mahogany doors, one could only wonder what they held, and imagine such horrors as dirty linen. There was a "presentation" clock whose hands hung in dejected arrest at 7.2 5. There was a rosewood piano of the 1878 type.

On each of the three "easy" chairs of slippery leather lay some leaflets advertising the miraculous cures of an Irish doctor by the absent-treatment method. Over the room hung a smell of that morning's lunch and a month of breakfasts. In the far part of the room, giving on to the street, three tables were halfheartedly laid for dinner or supper. They stood with white faces upturned to the ceiling, mutely praying that somebody would be sent to dine at them—knowing that nobody would.

1TNSIDE, the house was hushed; nothing but 11 the slip-slop of the chambermaid and sometimes the tinkle of a distant telephone-bell. From the kitchen of the station-restaurant came a drone of clattered plates that never developed and never paused; and the noise of these plates dropped through the hush on to the brain with the screaming monotony of the Chinese water-torture. I wondered—and so cut off from the world did I feel that I murmured the wonder on my lips—I wondered: "Why did I come in here, and how am I going to get out?" There was nothing to stop my going. The parlour door was open, and the passage reached the street-entrance in ten paces. Yet five minutes of that room had so affected me that the act of getting up and breaking that dusty hush with footsteps needed a decision which the hush had already sapped.

To think, I murmured, that this abomination dares to call itself a hotel. The Cote d'Azur can be forgiven, as showman's license, but Hotel. . . . To think that, right outside a great station by which Americans and many Europeans enter London, there stands a trap like this to catch the unknowlcdgeable foreigner and give him libellous notions of English hotels. In Bootle, perhaps; in Wednesbury, in Ashton-under-Lyme, one would visualise such a place, not as an obscene joke, but as suitable to the landscape. But here, in the centre of London, within two minutes' walk of the Strand, to find this bit of Sunday-aftcrnoon-inGalashicls. To walk from the magnificence of the main hall of Waterloo on to this panting corpse of 1878. . . .

An idiotic music-hall song came to me: "The body is upstairs."

As I sat there, 1 could feel its air descending upon me like a hovering sack about to envelop head and shoulders. I wanted to sing or yell or stamp. If only those whispering footsteps would stop. If only that husky voice would stop using the telephone. If only there wasn't the feeling of being spied upon through a "dispense" shutter. If only someone would come in and roar for supper, or throw something at the walnut overmantel, or in any form kick up hell's delight. ... I had an insane thought of bringing some ghastly life to the place by ringing the bell, and mortifying flesh and spirit by ordering an ashen dinner at one of the tables stained by last year's flics. At any moment I could have gone out; yet I could not get up and walk out; 1 could only sit and think of all those dim, rainy things.

AND then came something definite. Feet descend ing the stairs. Awkward, slow feet, but feet that came down with good round thumps. The feet banged along the half-lit passage and stopped outside the door. For some seconds they were still; there was a noise of heavy breathing.

Then he swung round the door, swayed a little, and came in. He was a man past middleage, shapelessly stout, with wispy hair and depressed moustache. His clothes had the appearance of being flung off at night and flung on in the morning. Third-rate commercial traveller from the provinces, I said; losing pace and slipping down in his job. As he came under the shivering gas-jet, I knew how this hotel lived: I saw in one glance that he was the perfect guest for the Hotel Cote d'Azur and for this room and those fly-blown tables. His face was heavy and steamy; the checks sagged; the eyes were lustreless.

He went to one of the easy chairs, as though he were making a journey to it. He sank into it, grunted, and looked at his boots. He looked at the fire, at the ceiling; then into the shadow by the 1878 piano where I sat. I was grateful lor his coming in because, though he was in the key and tempo of the place, his coming broke its spell upon me. I got up. He waved a hand at me. Waved it twice. Then said: "Di'n see you there. Don' run away, mister. Rotten night. Hope not intruding. Don' want intrude anybody. Don' lemnic disturb. ..." I saw that I must get away. But in sinking to the chair lie had moved it, and it now stood athwart me and the door. "No need run away. Rotten hole—eh? jus' place for summer holiday—eh? Have a drink?"

I thanked him and spoke of a train, and edged round him. His voice changed. It broke a little, and the tone was entreating. "O-oh, don' run away. Now, don' you run away." He made a prayer of it, with aimless waves of a large hand. "Like a bit of a chat now an' then, 'fyou understand me. Staying in place like this. You staying here? Ah—thought not. Didn' s'posc you was. Got more sense. Only fool'd stay here."

To engage his attention while I finessed round his chair, I said: "Well, why stay here? Plenty of decent hotels round here, no more expensive than this. Goodnight."

(Continued on page 100)

(Continued from page 56)

don' understand. I got to stay here. Have to. I'll tell yeh. (That is, if not boring yeh). Known this hotel for years. Thirty-two years. Come here every year. Filthy Hole. Don't go, mister—er—mister I-didn'tcatch-the-name."

"I didn't give it. Good night."

"Ah . . . Ah . . . No. Didn't give it. Wise man. Don't matter. But don't go. Not in hurry ten minutes. Plenty o' trains. Too many."

He put a fat arm across the door, and it was clear that I could not pass without deliberately taking hold of his hand and moving it; and I did not want to touch that hand. His presence was the climax to the hotel; his threat of conversation was its anti-climax. It was exasperating, but I could do nothing but surrender and try to make myself interested in learning why this fat mass had come every year for thirty-two years to a Filthy Hole.

I sat down. He reached across the arm of the chair to a bell-push, and heaved himself half out of the chair in reaching it. He fell back like a sack. Before he had fully pushed it, the slip-slop was there. "Double, Jessie. And this gennelman, my friend —jus' take his order." When the order was filled, he took a long drink, sat back, and made noises of "Rrhmm. Rrhmm. Chjrr-rrm." He folded his hands and looked at The Stag at Bay; looked across the room, and saw me.

"Ah . . . Ha! Going tell yeh. Ah— filthy hole. But every year—thirtytwo years—never missed. Tell yeh. (That is, if I'm not boring yeh.) Jew know why I come this filthy holer Tell yeh. Rrhmm!

"I was twenty-three, then. Ormskirk I come from. I was living there then. There was a girl . . ."

I squirmed in my chair. I felt the room closing in again. The hushed room and a fuddled old man who was about to tell me the story of his life and his silly love-affairs; when five minutes away were the lights and the shops and the Strand and the bells of St. Martin's. I think he saw the squirm.

"Wonder why I say that to stranger, eh? Think it's not quite decent tell things like that to stranger? Ah —don' understand. Tell it to stranger any day; never told it to friend. Never could tell it to friend. See? D'you know what love is, mister? Real love. When you're not just man and woman, male and female. When you don't think of sex but when you're something bigger and cleaner'n male and female?"

He was sitting upright now, leaning forward. He seemed in half a minute to be sobered; his voice was firmer and the syllables were clear. "Know anything about that?"

"I think we all have it once in our lives. Usually when we're schoolboys."

"Ah. Yes. Well, I was twentythree, and I had it then. She was twenty." He repeated softly, to himself: "She was twenty. Met her at a friend's house. I was on the road,

then; not much mdney but going well and good prospects. Her people— the old man—parson. Poor as misery, but proud . . . Proud! The pride stuck out that you could have cut bits off it. Well, I come along. Would he look at me? Would he look at Judas Iscariot? Me—a shoving young commercial—wanting to meet his daughter. His daughter! His (laughter was to marry a gentleman or nobody. If I'd had two-thousand a year he wouldn't a-budged. I was all righf, mind yeh. He said so. Nothing against me, only—I wasn't a Gentleman. That was enough. I wasn't a gentleman; but he was sure from what he knew of me that I had enough delicacy to realise that the matter was closed."

Before this intimate confidence I could not bring myself to look at the man. I stared into the black grate, and, with my eyes turned from him, my mind took impressions of him; and out of that fatness and softness peeped something as slim and wistful as that figure which Charles Chaplin has created for us; something that used to be called the Good and the True; something horribly alien to that parlour.

"Well, my delicacy was all right, but, y'see, we were young. And whether she knew what the old man meant by a Gentleman, or not, or whether she mistook me for a Gentleman, or whether she thought I was more interesting than her father's Gentlemen, I don't know. I only know we took no notice of him, and we went on meeting. Evening after evening. Sometimes in the shrubbery. Sometimes among the rhododendrons at the back of the churchyard. Sometimes right outside the town on the hills. Summer nights. Winter nights. September, when you could smell damp leaves and the Hunter's moon was up. In the Spring, in May, on Sunday nights she'd slip out and come scuttering round the vicarage wall in her white frock—I could see her yards away in the dusk, like a big butterfly. . . . Night after night— and me waiting there. . . . You know how it is when you're waiting like that—eh?—and the smells of flowers round you, and the night and all, and . . ."

His voice dropped into the fuddled sing-song; and all the time, above it, rose the restaurant's unending accompaniment of plates and dishes, making a concerto for Voice and Crockery. He paused. I lit a cigarette. He blinked, sat up again, and went on.

"Ah. Summer and winter nights, for a year and a half. Sometimes for an hour, sometimes only for ten minutes. But we met. Oh, my God, we met." He shouted this; then drooped his head and stared at the carpet. 7. thought the anecdote was ended, but with a quick movement, he looked up. "Not boring yeh, am I? Yes, we met all right. She was—she was— she was one o' them serious-laughing ones, if I make meself clear. You know—steady, quiet, good, but eyes always laughing. See a joke as quick as I would. If I see anything funny I'd just flick an eye at it, and at her and slic'd see it in a second. Even them that didn't feel like I felt about her were always glad to meet her and see her go along the street. I can't describe her; no hand at that sort o' thing. But perhaps you know what I mean. She was like—like getting up on a sunny morning after a real good night's sleep—know how you feel then? That's not really the way to put it—nowhere near it; but something o' that sort was the way she made yeh feel when you looked at her.

(Continued on page 101)

(Continued from page 100)

"Well, after a time the old man found out. He would. He was one of them ones that're always snooping round finding out other people's affairs. He put her through it then. Tried to make her take an oath not to see me again; but she wouldn't. Then he kept her to the house and lectured her every half-hour. Called her meeting me Indecent, and used a lot of other foul words—at least, words themselves was all right, but using the word Indecent about her was as foul as swearing. Understand me?

"Well, 's I say, I wasn't doing badly then. Matter o' fact, doing well, as money went,—four pounds a week and commission; so whatever I couldn't give her in the Gentleman way, I could give her other things.

I could give her more food than she got at the Vicarage—she never really had enough to eat—and warmer clothes and a better home; and though I oughtn't say it—a happier home. Y'see, we were in love—both of us. There wasn't anything else in the world for either of us. . . . Well, we planned it. Friend of hers—a girl —used to smuggle letters in and out; and we arranged just the sort of little place we'd have, and the kind o' book-cases we'd have—we were both big readers—and the sort o' kitchen she'd want—one with plenty o' windows and room to turn in—and that we'd have hors d'ceu-vres and omelettes and salads for dinner 'stead of the lumps of hot beef and cold scraps she'd lived on in the Vicarage, and . .

He paused, and again that elf peeped from the big damp face. He stared at the carpet, muttering. I was interested now, and recalled him with: "You were saying . . ."

"Eh? Oh—er—yes. What about another drink?"

"Not for me, thanks. You were saying . .

"Ah, yes. We'd got it all planned after a week or two. She'd slip out in the morning—the old man couldn't keep her shut up all the time—and first we'd go to London. Get married there. Then look round. My firm were good people, and I stood well with 'em. They had a big branch in Leicester, and as living in Ormskirk after we were married would a-been uncomfortable—not to say indelicate —I asked my people to transfer me to the Leicester territory. They did.

"So then everything was all right. We just lived looking forward. You know. Everything was lit up. Streets and tramcars and shops and my everyday work. All seemed different, like, as though they'd been kind of—er—

kind of—sort of—if y'know what I mean—purified." He whispered the word. ("Sure I'm not boring yeh!")

Because I was really interested, I could only give him a fatuous "Not at all. Go on."

"Well, the morning come—morning we'd arranged. June it was, I remember. Chrrm! . . . Urrr. . . . Well, I picked her up outside the town. I hired a car to meet her, and I had the car run us along twenty mile down the line to a junction where we could get the through express. . . . Yes; half-past nine, it was, we met. June. Out in the country. She was wearing one of those little fur hats, and her hair—that dark brown hair that goes with serious and—er—unusual natures—her hair was sort of blown about her forehead and her ears. Out there on the moor. And her eyes were bright. And she'd got a colour from hurrying. There she was, waiting for me. And the morning—soft and sparkly and—sort of water-colour morning—soaked right into me, if you understand my meaning. Ever felt like that? It seemed as though we'd kind o' jumped into it, to bathe. What you might call a Poetry morning. I mean, it made you think of Shakespeare's songs and Herrick's songs. (Perhaps that ain't clear to you. Perhaps you're not much of a reader. Doesn't matter.)

"My God, it was a morning! . . . Minimum. Rrhmm.

"Well, we got the train all right, and I fixed it with one of the dining stewards to shove a Reserved slip on our carriage. And then, for the first time since we'd met, we were together without having to think how the clock was going. Four hours of it. Ever had that for the first time? We had lunch on the train. She'd never had a meal on a train before. She was as excited as . . . Wasn't used to eating with the sway of the train, and spilt her soup everywhere and laughed like anything about it. All down the railway line was flowers. I dunno the names of 'em, but—flowers, y'know—blue and yellow and white and pink. All fresh, like. And I felt —'fyou understand me—I felt just like them flowers. Twenty-one she was, and full of twenty-one. You'll know what I mean when you get to my age.

"I brought her here. I'd found this place when I'd made my first trip to London. Found it on a foggy night. Got lost wandering round here. Dark arches and little passages. Then I see its sign, so I thought I might as well make it my place, seeing it was near the theatres and looked cheap. And I liked the name. I knew it meant the Mediterranean. I'd read a bit about the Mediterranean, and seen pictures of places there, and was always promising myself to go there when I'd got on a bit. I was going to take her there when I could, and I'd often talked to her about it, and about the sun and the songs and the peaches and the olives, and the sort of ease of everything and the freedom. You know—there's a French -word for it. Sitting outside the cafes in the gardens, and the 'strordinary blue sky and the colour of the sea. And doing as you liked and nobody saying anything or asking questions. Just the sort of places, they looked, for living life and loving every minute of it, like we was meant to, if you understand me. (Would yeh mind pushing that bell?)"

(Continued on page 102)

(Continued from page 101)

I pushed the bell. He sat back. In distant parts below, the telephone rang, like a telephone of elf-land.

"Well, I was telling yeh—I'd only been to London that once, and this was the only hotel I knew. I could have afforded to go to one of the big ones, but I was young, and seeing the business we were on, I was a bit nervous; not quite sure of meself or of how you went on in them big places, or whether they mightn't ask questions. I knew this place, and as I'd found it a quiet sort of place, I thought it'tl do for us just two or three nights, until we'd got things a r ranged.

"So we come here. Had some tea, and then went across the bridge, and had a walk along the Embankment and the Strand and up to Oxford Street and back again. I go for the same walk every year I come here. I could do it blindfolded. . . . Well, then we come home—I mean, we come back here and sat in this room. We had a bit of supper over there— that table by the window—not the first one, the middle one; and then she had this chair where I'm sitting now, and I sat in the other—over there, from eight o'clock we sat here, just saying a word or two, but most time sitting quiet. We didn't need words, y'see. It was all so—so—wonderful. Just sitting there together was enough. You know. We had the room to ourselves all the evening. Nobody even peeked in. Perhaps you think this room's a dirty stinking hole that wants the air let into it. So it is. And yet.

. . . It's just the same to look at now, as it was then. Same furniture; same arrangements. Never altered it. Don't think they've ever cleaned it. And yet . . ." His eyes stared at nothing, and as I sat waiting for him to resume, the room seemed to shed its musty despair and to take on the perfumed sadness of past happiness: withered flowers; forgotten songs and dances; old letters. "Well, here we sat, all lifted up, like. In two days we'd be married; even special licenses keep you hanging about a bit; but we felt already as though we were.

"Well, it come eleven o'clock, and I could sec she was tired. So we got up. I'd booked two rooms for us, and I told her her number, and we said good-night. Said good-night for about five minutes—right there by the piano. Then we went up. Couples

had been slinking up all the time; it was all couples here. My room was near the top of the stairs—hers was further down. As we got to my room I stopped a second to give her a last look. She was standing just a little way off. A gas-jet lit just half her face. (Chrrmm!) We stood that way—silly-like—for nearly a minute, as we always had when saying goodnight at home, and she was looking straight at me like she'd never looked before. . . . Then all of a sudden she smiled, blew me a kiss, and trotted off. Little light steps all down the passage, into the dark part."

He stopped sharply and leaned forward, elbows on knees, and scowled at the fire. His head nodded. He gave two grunts. Then he sat back and stretched himself full length in the chair. I waited. From the passage came the husky whisper of slippers on oilcloth. "And then . . .?" I asked. His eyes were closed. "And then?" "Eh?"

"What then?"

He lifted his head and stared round the room, and fixed his eyes on the piano. For many seconds the room was still. A lump of coal fell from the fire. As it fell it started a flame. The flame spurted and passed to some small cinders and set them glowing. There was promise of a fire: then flame and glow faded. I repeated: "And what then?" He seemed to jerk himself back to his story. "Eh? What's that? Eh? Oh . . . Oh, there wasn't any Then. That was the end of it."

"The end of it? She went back? Her father . . .?"

"Went back? No. No. She never went back. She went on down the passage to her room, and I stood looking after her, and remembering her look, and wondering. And that was the end of her."

"The end? How?"

He glared at the carpet and spat an answer. "Damp sheets. Pneumonia." His lips closed; then he banged the arm of the chair. "Yes, and the hell of it is, it need never have happened. Look here, mister, you're young yet. Take a bit of advice. As you grow older, you'll learn that the things you'll be most sorry for in life aren't the bad things you've done, but the things you hadn't the pluck to do. Any weak fool—like me—can say No to Temptation. It takes courage to say Yes. If we'd had a bit of courage when she stopped outside my door and gave me that look ... If we'd only taken what life offered. . . . But we didn't. We were Good. And so she went on, and . . . Y'see, my room was all right. My sheets weren't damp."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now