Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Far West

An Author Gives His Impressions of the Country Beyond the Mississippi

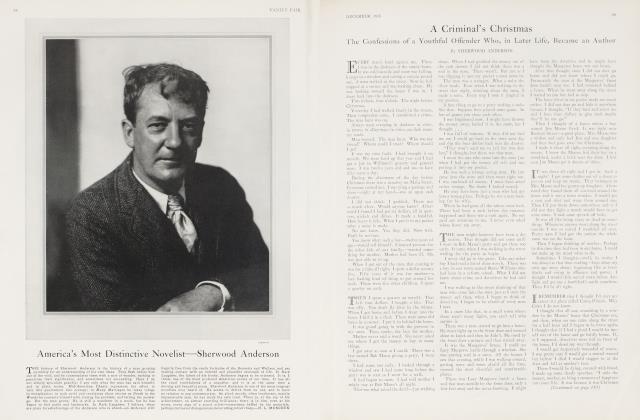

SHERWOOD ANDERSON

EAR MONTE: Memories of Joaquin Miller. He went to London, they say, and smoked two cigars at once. As I understand the matter he had cigars stuck in both corners of his mouth. Also he wore big cowhide boots and a wide western hat. He went to literary dinners in London outfitted like that. It made his everlasting reputation. The English thought he was just lovely. Nothing helps a writer over here like getting a London recognition.

Do you remember, Monte, when we were both advertising writers in Chicago? When the president of our agency got drunk he used to shake his long finger under our noses and declare Joaquin Miller the greatest poet that ever lived. He always recited Columbus when he was in his cups. You will remember how his voice trembled and sometimes, when lie was a little more than ordinarily lit, the tears would come into his eyes.

"Sail on, and on and on." Oh, boy!

I understand that in San Francisco they get twenty-five cents for showing you where the poet sat when he did it. I may be wrong. It may be fifty cents. I didn't go.

RET HARTE lit out for London too. I can remember seeing pictures of him when 1 was a boy. He dressed very carefully and looked like a very proper old English gentleman, sitting in a club. For some reason, on the coast, they do not make the fuss over Bret Harte thev do over Miller and Stevenson.

R. L. S. is their chief pride. They mark down every bench lie sat on, every tree he leaned against. "Here leaned Robert Louis Stevenson. May his soul rest in peace", etc., etc.

1 have been on the coast for a year and a half now and have been intending writing you for a long time. Now I am on a train cutting out for New Orleans. T here is a man from the Middle West has the berth above me. He has heart disease and dared not stay on the coast for fear there would be an earthquake. He's wrong. They don't have earthquakes out there. Ask anyone on the coast.

The man says California is in for a big boom again. Ten years ago he went to Florida, near Miami I think, and bought a farm. He hung on and hung on and in this last big Florida boom cleaned up. He took the money he got and bought land in California. In the long run, he savs, people will be less scared by earthquakes than hurricanes. Hang on and on and on. He says the American people have got to go somewhere, have got to be on the move. They'll surge back westward pretty soon now. Where do you think the man on the train lives while he is waiting to make these clean-ups? In Chicago. He told me so himself.

At first, just after 1 saw you and when 1 lit out for the Ear West, I was around the desert states. I went to Phoenix and Reno and Goldfield and Virginia City. We went from a place called Carson City in Nevada to Goldfield in .t car. T here were two men with shares in mines to sell, a dentist, a doctor and myself. T hey took me because 1 was a writer. You know how it is. If you are a writer, business-men, fellows who have mine shares to sell and real estate men will take vou anywhere. They think you'll write about your trip. "It's publicity," they say, "there's nothing like publicity."

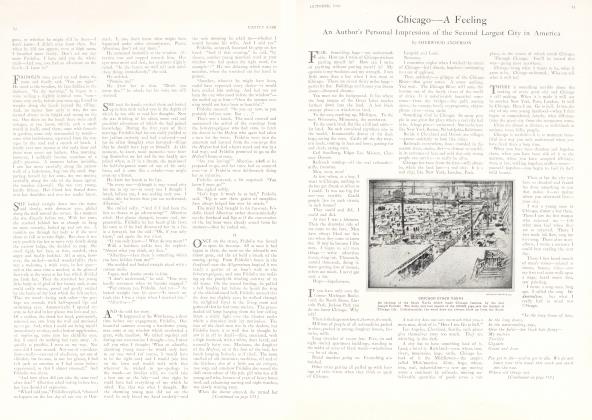

HTMlE ride down over the desert was somcII thing never to be forgotten. What looks Eke just a long dip between two hills is thirty miles across. You come to little towns—not a soul living there any more—empty houses standing just as they were when the miners walked out—mining machinery lying about.

There is a place that used to be a saloon and hotel. The stage coaches stopped there. The mining men in the car with us talking of old times. They used to haul the ore from Goldfield over the desert hundreds of miles to get it to a railroad. At Goldfield the ground rotten with gold. When the miners left the job at night—three, four, even five hundred dollars concealed in their pockets. They called it "high-grading" the mine owners.

Jim Corbett, Jack Johnson, Tex Rickard, George Winfield of Reno. A dozen other great names of the western flush days murmured in my ears as the car went at thirty miles an hour over the desert sand roads—seemingly getting nowhere. When we had at last achieved the top of a hill, towards which we had been flying for an hour, there was another, just like it and also thirty miles away. Imagine the long roll of the sea, wave tops thirty miles apart. You've got it.

Occasionally, during the day, we stopped the car and got out to stretch. At one place, I remember, we came to a house standing in the very middle of one of the long dips. Sage brush and yellow sand. Not a tree in sight. A man lived there who writes cowboy stories. There was a fenced space back of the house and five cows in it. 1 gathered that they, and the lonely life out there, were for the sake oi local colour, lie did not tell me so. What he did was to reach under the house and pull out a bottle of whiskey. Apparently he wanted us to stay. When 1 was introduced as another writer he looked at me with questioning eyes. 1 had never heard of him or he of me.

Into my ears always being poured the tales of the past. Rawhide, Bowie, Virginia City, bad men with guns, vigilance committees, streets of mining towns filled with millionaires, two hundred thousand lost at faro in an evening. What the hell! Who cares?

HTAHE states of Nevada, Arizona, Idaho, New II Mexico without enough people left in them to make a respectable suburb for an eastern city.

Everything happened so long ago. I'm not an old man. It happened when I was a boy and when 1 was growing up. That day on the desert in the car all the men of our party whispered me the same story. "When you go on west, over the mountains, to San Francisco and Los Angeles, you'll hear big tales. You'll hear what men have done out there. Where did they get the money to do it with? " Men standing on the desert and waving arms toward dimly seen distant mountains. "They got it out of these hills, every cent of it. Then they left us flat."

All the men of the desert states clinging to the notion that, if someone would make just one big strike, it would all happen over again. They have to cling to something I suppose. They can't farm.

Goldfield—the strangest American town I ever visited. We got there in the evening and put up at a big hotel. There had been a fire,— half the town swept away. It would never be rebuilt. Most of the houses empty anyway. The hotel, a huge ruined place that had once housed hundreds of millionaires, where crowds gathered for world championship prize fights, with a bar as long as Hinkv Dink's in Chicago when we worked together in that town, tiled dining room floor—a good many of the tiles fallen out—the hotel housing perhaps three guests.

A few men standing about in the big lobby. They were dressed like stage mining men. I had a hunch the movies were responsible for that. Not a man of them had put a pick into the ground for years.

Waiting for easterners with capital to invest. Our party created a little furore. When 1 was shown to my room on the third floor it seemed to me that empty rooms were stretched away for miles and miles in all directions.

Later I came down into the hotel lobby and was buttonholed by mining men. The dentist and I escaped. It was dark and we walked aimlessly about and got into a street of prostitution. Worn out old prostitutes waiting to buttonhole. Two or three of them came out of a house and stood staring at us under a street lamp. "My God—easterners." Hope in old bleary eyes. The good days come again. We might be investors.

is what I have been wanting to write to you about, Monte—my impressions of the Far West.

l ime, space, everything a little out of proportion for me.

1 get it that everything that has happened out on the coast has come in long surges like the crests of the hills you run toward—out on the flat sage bush deserts. Everywhere else in the country things moved more slowly. The cast was settled slowly—people coming over in sailing vessels in the old days. When we were boys in the Middle West old people used to talk about the trip over. It took thirty days sometimes. They settled in New England and the eastern states and their sons came on out into our country. They were all farmers, looking for cheap land—a place to settle down in, to stay in. In the South the same thing happened. Cotton raising with slave labour was hard on the land. All right. Plenty of new rich cheap land west. Down South you hear stories of the grand trek westward, into Mississippi, Alabama, Arkansas, Texas. The old baron and his family on horseback or in carriages, long lines of wagons, slaves, cattle, pigs, even chickens working their way westward, often not more than four or five miles a day.

The west coast far away—outside the picture. Spaniards and Mexicans lived out there. Read again Dana's Tzco Years Before the Mast.

Then the gold rush. 'That brought in the young blood with a bang. It's a pretty dull book and full of bad jokes, but Mark Twain's Roughing It docs give a good picture of what life was like out there then. I read it again while 1 was on the coast.

AT you get is a sense of the rest of the country as something too far away. How can they help that feeling creeping in? Even now, on the best trains, you get the feeling. It's like going abroad. The desert is like the sea. Imagine what it must have been like to the crowd that surged over it looking for gold. If they went by sea it was just as far, just as difficult. The dream in every man's breast to get out there, dig out a few millions in gold and get back east—"back to the states", they used to say.

In Los Angeles an Italian boy was shining my shoes. "How's things in the old country?" he asked, A questioning look in mv eves. He explained. "New York's the old country to us wops out here," he said.

That first masculine surge of people into the country passed and there was a quiet time. Then they found and put on the market another kind of gold—golden sunshine.

That got of course a different kind of crowd —more respectable—not so full of pep. It got the old ones, the sick ones—people who wanted to retire, people who wanted to sit all day in the golden sunshine. It isn't exactly the finest kind of people to bring into a country, small retired merchants from the Middle West, retired farmers. They live in bungalows. You know nothing grows out there unless you bring water to it. If you can get the water anything will grow. We, of the East and the Middle West have this notion—put into our minds by

the advertisements—of a sea of roses stretching away in all directions as far as the eye can see. What stretches away is brown sun-burned hills —more beautiful than seas of roses could ever be, I think.

The ugly thing is the bungalows dropped down all over the hills. They arc the ugliest things the brain of man ever dreamed and all filled up with retired people. Nothing to do. Lord what a life.

San Francisco is something. It is a really beautiful town with its sweet hills and its cold crisp air. Often heavy fog rolling in from the sea. The bay there is the most magnificent thing I've seen in my wanderings.

I went up north to Portland and Seattle.

Rain, a cold fog, great hills, great trees. The people seemed too small. They hadn't touched it yet and I could get no sense of them. I guess they haven't been there long enough. I like an old country, old houses, old streets. Chicago, when we lived there together, was always too new for me. I like a country into which people have come because they needed to come to make a living, where they intend to stay. Then I like to get there after they have stayed. I presume all that northwestern coast country needs staying with.

OWN south it's something else. It was all rather grand to me. Los Angeles seemed a gaudy madhouse. All the strange hopeful people of the Middle West who had money enough must have gone there looking for paradise. No lack of energy down south. The days roll up with endless sameness. Every day in Los Angeles is just like circus day in the small Middle Western towns. That's where they've got the sunshine, the movies, the oranges. That's where they know how to sell town lots. Every day when I was in Los Angeles I woke up thinking—"Today it will blow up, deflate." It didn't. I half believe it never will. Such a mad town you never dreamed of. Wide streets, more automobiles than you ever saw, even on Fifth Avenue, in Hollywood—really a suburb—people going about dressed as Christ, Julius Caesar, Ivan the Terrible. In Los Angeles, women dodging out of doorways. One of them hails you. She looks like a New England school-mistress— lean, energetic, determined. "Is that woman going to solicit me? I'm lost", you think. She's only an agent for a real estate company. You're all right after all. She wants you to go on a free excursion, ride in an automobile, have lunch at her expense.

Los Angeles taught Florida how to do it and when it looked as though Florida might outdo the land of sunshine they discovered oil. The city seemed to me the top, the very peak of everything industrial America means. It is sanitary, it is alert, it grows and it sure does advertise.

And after that, to top things off, I went to Tia Juana.

ITT'LASH men of all the world, gamblers, IP touts—all the old worn-out racing men come to life again. I saw old sports I thought were ready to die when I was a sport myself— some twenty years ago. The easy picking had brought them back to life again. I can't write about Tia Juana. It would take a book.

After that the train for home. Home for me means most anywhere cast of the deserts. I could never feel at home out there.

I'm in the desert as I write. It stretches away like the sea. It may be just the desert between the coast and the rest of the country that makes it seem so far off.

Well, I started to give you my impressions of the Far West. There it is, I cannot think of it without thinking of the deserts and the mountains. When I was a boy the school books called it, "The Great American Desert". It separates the Far West from the rest of the country, separates the Far West from us. People out there deny the feeling but I'm sure they have it. They feel out of the circle, too far away. It leads to an ovcrvalua(Continued on fege 104) tion of the East and Eastern men. As I said in the beginning things get out of proportion.

SIGNS OF THE TIMES By GEORGE S. CHAPPELL

1 think that I have never seen A fairer hiker than Irene That day I checked my motor swift To give the little dear a lift.

Then, as we sped o'er plain and hill,

I showed my one-armed driving skill When, lo, a sign upset mv nerves:

It read, "Attention! Dangerous Curves/"

Her head upon my shoulder pressed And straying locks my cheek caressed While ever and anon the lass Would murmur softly, "Give her gas." Across the countryside we flew Till suddenly, athwart the view, Another sign my joy impaired, Announcing, "Shoulders liein g Re paired."

"Now, curses on the things!" I cried, And she, who nestled at my side,

A question whispered in my car,

"Do you believe in signs, old dear?" "Alas, I do," "Then look," said she, And there, for all the world to sec,

Sign number three its message stated: "Tourists " it said, "Accommodated."

(Continued from page 40)

It wants something that will, I presume, come. Los Angeles is a city built for the automobile, whereas all of our Eastern and Middle Western cities were built for the horse. It may be the whole Pacific Coast is but waiting for the airplane to come into its own. There are no deserts and mountains in the air.

Just now the Far West wants something to take away the feeling of being too much outside. The whole

west coast civilization may be but a thrust into the future.

It is outside all right. That shoe-shiner in Los Angeles expressedsomething that —whether they are ready to admit it or not—the whole west coast feels.

"How's things in the old country?" you'll remember he asked.

And then the explanation.

"New York's the old country to us wops out here."

It isn't only New York.

Everything east of the mountains and deserts becomes the "old country" when you're out on the coast.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now