Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAn Auction Angle on Contract Bridge

Showing That the Best Players at the Popular New Game Are the Experts at the Old

R. J. LEIBENDERFER

CONTRACT BRIDGE has now been given a far and wide spread try-out, and with rather surprising results. You will find one group of players, who took up the new game very enthusiastically and are now giving it up and returning to Auction. On the other hand you will find a still larger group, who formerly regarded it with great disfavor and who are now playing it to the exclusion of Auction. The general opinion seems to be that Contract is a little like an olive—you must learn to like it. The Whist Club of New York is now engaged in codifying the Laws of Contract Bridge and is receiving the cooperation of the Knickerbocker Whist Club, The Racquet and Tennis Club, The Cavendish Club and the American Whist League so that the new code, when completed should be a representative one in every respect. The new code will be approved and adopted by the clubs named and will undoubtedly become the national code, superseding all others. This new code should arouse a general interest in Contract and may be the deciding factor in putting it over as the successor of Auction. It will be released for publication very shortly and the readers of Vanity Fair will then be given a summary of it, together with its immediate and possible effect on the game.

One of the greatest objections to Contract, as now played, is the great number of conventions that have sprung up. The resultant confusion is so great that one prominent New York card club is seriously considering the publication of a club pamphlet, containing the recommendations of its Card Committee as to the proper bids and doubles at Contract, "As a matter of self defense", to quote a well known member.

Taken from every angle, Contract seems in the main an improvement over Auction, but it is on trial only. The future of the game depends entirely on the attitude players adopt in regard to it. If they regard it as an extension of Auction, to be played along normal Auction lines, it stands better than an even chance to make good. If, however, they try to make a different game of it, with new and more or less arbitrary conventions, it seems doomed to failure. So, let the lovers of Contract be extremely careful.

The following examples from recent and actual hands show how little the bidding of the true experts deviates from sound Auction principles.

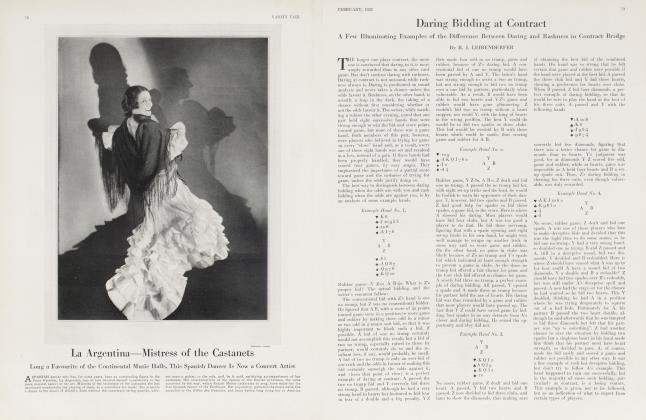

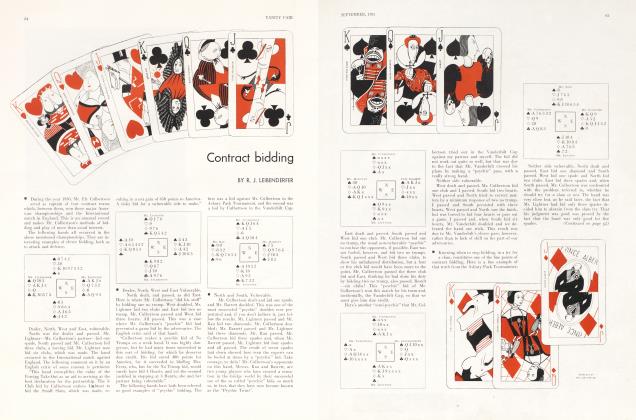

No score, Rubber game. Z dealt and bid three spades. If A passed what should Y bid? Y should unquestionably bid four hearts. Such a bid must be considered as a take out and as a denial of any help for Z's spade bid. The bidding in this hand is exactly the same at Contract as at Auction.

No score, First game. Z dealt and bid one diamond. A bid two hearts. Y bid two spades and B bid three hearts. What should Z bid with the foregoing hand? Z should bid three spades either at Contract or at Auction. The fact that he originally bid diamonds doesn't indicate that he has such unusual assistance at the spade bid and the only way to show this assistance is by bidding three spades.

No score, Rubber game. If Z dealt, bid one diamond and A passed what should Y bid? Y should bid one heart. The take outs or denials of partner's suit bids at Contract should follow very closely the Auction practice. At Auction, no player would consider passing a diamond bid with Y's hand so why do so at Contract? Don't let the fact that you are playing a new game prevent you from using as good judgment in take outs and denials as you would in Auction.

One of the prettiest problems of Auction is the proper bidding of two suiters and one of the drawbacks of Contract is the fact that it lessens the chances to bid them. For example:

No score, Rubber game. Z dealt, and bid one spade, A bid two hearts, Y bid three spades and B passed. When Z bid four spades, A was confronted with the difficulty just referred to, that is, the difficulty of showing two suits at Contract. He would have to bid five clubs and, if his partner preferred hearts, he—his partner—would be forced to bid five hearts. Either bid of five might be doubled and result in a tremendous penalty. The best thing for A to do in this situation is to pass and hope to defeat the four spade bid. The bidding, at Contract, is apt to get too high to justify the bid of the other suit on the second round and so many a two suiter is bound, in Contract, to lose out.

Even when the Contract player holds a hand that offers a chance for a slam, sound Auction bidding will obtain the desired result without any arbitrary Contract conventions.

No score, First game. Z dealt and bid one diamond. A passed. Y bid one no trump and B passed. Z now bid five diamonds and A passed. It is a practical certainty that a little slam can be made so Y should bid for six without any question.

No score, Rubber game. Z dealt and bid one no trump. A passed. Y correctly bid five hearts and B passed. It wasn't much of a problem for Z to bid six hearts and strictly in accord with sound Auction practice.

Once in a while, however a hand comes up that requires genius of a high order to handle properly. The following is a fine example.

(Continued on page 114)

(Continued from page 82)

HAND NO. 7

No score, Rubber game Z dealt, bid one club, and A doubled. This is perfectly sound Auction practice and equally sound at Contract. Y happened to hold a freak hand, one of value only with clubs as trumps, so correctly bid five clubs, a bid equally sound at Contract or at Auction. B and Z passed and A was now confronted with a problem that has no parallel in Auction. The stereotyped procedure would be a double, but A was too fine a player to be content with a "set" of one or two tricks, the maximum to be hoped for on the bidding, so he decided to bid six clubs. This bid evidently could not be regarded as a bid to take twelve tricks with clubs as trumps for the bidding of the opponents made such a conclusion impossible. The only alternative to consider was that the six club bid was intended to force the partner to bid six of his best suit of the remaining three. The six club bidder's partner correctly read the bid and bid six diamonds on four diamonds to the eight spot. Everything broke just right and A B made their six diamonds. It is inspired bidding of this type that makes Contract such an interesting and fascinating game.

HAND NO. 8

No score, Y Z a game in. Z dealt and bid one heart, A bid two diamonds and Y bid three hearts. B at this stage is under no obligation to bid, as Y Z have not yet bid for game. Z now bid four hearts and A and Y passed. B is now in an entirely different position than he was on the first round. His opponents have now bid for game and if they make it they will score game and rubber and the resultant large bonus. B, therefore, is justified in bidding five diamonds, knowing full well that the game cannot be made but also sure that the penalty will be small and probably save game and rubber. The five diamond bid was doubled and defeated only two tricks while at hearts Y Z would have made four odd, game and rubber. Don't hesitate to overbid in order to save the game and rubber, particularly when you are not vulnerable and when morally certain that the loss will prove a money-saving expedient.

In this respect also, Contract practice and Auction practice are the same.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now