Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAnalyzing the Auction Bridge Experts

And a Few Hands Showing the Super Tactics Employed by the Best Players

R. J. LEIBENDERFER

THERE is a wide difference of opinion among bridge players as to what constitutes a true expert at auction. The standards by which an expert is judged usually vary according to the group, or club, or community, in which he plays. Some seem to think that the writers on the game, or the teachers of it, (because of their apparently great knowledge) must be expert players, but this does not necessarily follow at all. Some of our well known writers on bridge are, it is true, expert players, but, because of the fact that they devote so much time and thought to teaching the game, they are deprived of the opportunity to meet the class of competition that makes a player a true expert. Auction bridge is like any other competitive game in that a player, if he wishes to be "on" his game, must play constantly, and with the best players.

Some people claim that the men who play for very high stakes must be the true experts—as they always seem to play better under pressure, to be, in short, good "money players". The good "money players" have probably the greatest following among those who like to rate and classify the true experts.

As an example we often read that this or that baseball player has proved himself a good "money player" in a world baseball series. By this term the sporting writers probably mean that such a player has the capacity to do his best work, and obtain his best results, under pressure, that is to say, when many thousands of dollars depend on his playing. But this coolness under pressure, and the brilliant play that results from it, cannot help but be of limited duration. No baseball player would have the necessary stamina to play under the sustained pressure of a world series during an entire season. So that the heroes of such series as these are not the leaders over years of play.

THE same principle applies to the so-called "money players" in the game of auction. If a man is accustomed to play for five cents a point, he may play far better for a rubber or two if he suddenly finds himself playing for fifty cents a point. But, if the latter stake becomes customary to him, his play will soon drop back to his level of skill at the old five cent stake.

I have played with a very great variety of players and for widely divergent stakes,and I have yet to see a player whom 1 would describe as a good "money player" in the proper sense of the term. I am of the opinion that, over a fair period of time, a man will play just as well, or just as badly, at five cents a point as he will at fifty.

There is, of course, a good deal more to the expert than mere mechanical skill. The qualities of heart and judgment are just as important, if not more so, than an ability to play his cards. One player of my acquaintance, though he possesses flawless mechanical skill, could never be ranked with the best players because he lacks certain other qualities which the true expert must possess. Contrariwise, other players may have these qualities to an unusual degree and yet lack the finished mechanical skill which is also necessary in a real expert. Courage and psychological insight must all be combined with purely mechanical skill before a player can really be called a super-expert.

There can never be a perfect auction player—one who never makes a mistake—as the qualities of the human mind, no matter how unusual or keen, arc only finite, while the problems of auction and the possibilities of unexpected card combinations arc, to all intents and purposes, infinite. But the super-expert must certainly possess that rare gift of being able to perform at his best under any and all conditions. It is probably this quality that most people have in mind when they speak of the "money player", but that quality is only the result of other qualities which the true super expert must also possess.

Here are a few examples—taken from recent tournaments—of the expert's peculiar insignt and strategy in handling situations, whether in bidding or in play.

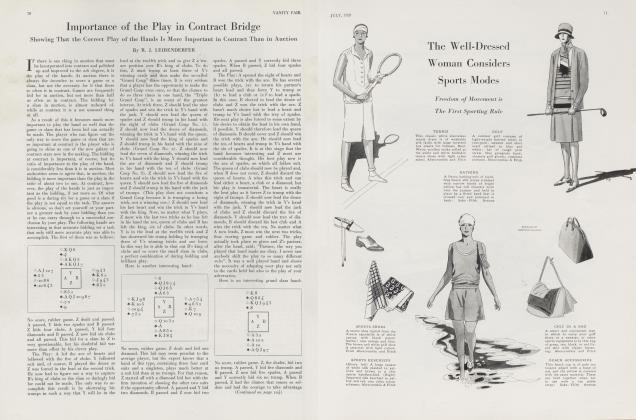

No score, rubber game. Z dealt and bid one spade; A bid two hearts and Y passed. Here is where B, the expert, had to do a little thinking. The natural thing to do is to bid three hearts, but B wanted to get the bid as cheaply as possible and yet be sure of rubber. He felt that if he supported A's heart bid at once, it would reveal the strength of his hand and so incite his opponents to the overbid of a trick or so to save game and rubber.

On the other hand, if he were to conceal the heart strength until such a time as would make the bid appear forced, rather than voluntary, he might be doubled but would certainly not be overbid. In this way only could he be sure of the game and rubber. So B bid three clubs, apparently denying help for his partner's heart suit. There was no flaw in this strategy for if his opponents should pass and let him play the hand at clubs, he could certainly make five clubs. The distribution of his hand, however, was so "freaky" that he was certain there was going to be bidding and lots of it and he was right. Z bid three diamonds, A and Y passed and B, keeping up the deception, bid four clubs. Z bid four diamonds, A and Y passed and B, still keeping up the deception, bid five clubs, Z bid five diamonds and A and Y passed. Here was B's opportunity that he had so clearly visualized on the first round of bidding. He now bid five hearts. This belated heart assistance made it appear that B feared that Y Z had a game in diamonds, and was making a wild try with a five heart bid to save game. Z doubled and A and Y passed.

"B WAS clever enough not to redouble for fear of driving Y Z to five spades or six diamonds. He felt that he could defeat such a bid but not enough to compensate for the loss of the rubber and the doubled contract. B's strategy worked out perfectly for lie and h s partner just made five odd in hearts, game and rubber. If lie had bid the hand in the normal way, Z would have bid five spades to save a possible game which B would have been forced to double, and which could have been defeated by one trick. B's bidding in this hand was very clever and deceptive, and worthy of the term "Super Auction".

No score, rubber game. Z dealt, bid one heart, and A bid one spade.

Y was a student of psychology as well as an expert, so he decided to try a little psychology on his adversaries. He had a very doubtful raise in hearts but he didn't want his opponents to go game and rubber without a struggle. He, therefore, bid two diamonds, figuring that the bid couldn't do any harm for if his partner had a really good hand, he would rebid his hearts and then he could afford to help him and yet mask the strength of his heart suit. B passed, Z bid two hearts and A bid two spades. Y now had his opportunity to help his partner and mask the strength by an apparent bluff—so bid four hearts. He felt that if this bid were doubled and defeated he would still save the rubber. B and Z passed and A bid four spades. Y had played his part to the limit and so passed. B passed and Z bid five hearts. A now doubled and all passed. Much to Y's surprise Z made five odd, game and rubber, while A B could have made five odd in spades, a bid they would have made if they hadn't been fooled by Y's deceptive bidding. It was certainly a good example of expert tactics.

Continned on page 124

Continued from page 85

No score, rubber game. Z dealt and bid one no trump. A considered the situation and decided that if he were to save the rubber he would have to do a certain amount of deceptive bidding. He also was a psychologist, so he bid two diamonds, the suit absent from his hand. Y bid two spades and B bid three diamonds, which Z doubled. A now decided that the "absent" treatment had gone far enough so bid three hearts, Y passed and B bid four clubs. Z doubled and A decided that he and his partner had at last found the suit best fitted to save the rubber at the least possible cost. All passed and A B were defeated by one trick. At spades, Y Z could have scored four odd, game and rubber, and, as they lost it on the next hand, A's "absent" treatment proved most effective.

If A had bid his hand in the normal way, Z would not have had the opportunity to make, as he thought, such a profitable double and as a consequence would have helped his partner's spade bid. A's bidding in this hand is a fine example of how a superexpert forges a weapon from his very weakness and makes a singleton perform the work of aces and kings.

No score, rubber game. The final bid was five clubs by Y. This had been doubled} Y Z had won four tricks and A B two tricks. Z was playing the hand. It was his turn to lead, so that if he were to make his bid, he would have to make the balance of the tricks. At this stage of the play, Z knew where every card was, so that the play of the last seven tricks is given as a double dummy problem to illustrate how the expert makes the so-called end-plays that come up so frequently in auction. Lay the cards out and try to get all seven tricks against any defense. It will not be easy, so consider the brand of skill that the expert displayed in making this series of seven plays in an actual game.

Analysis: Z led the four of spades and trumped in Y's hand with the five of clubs. Y now led a heart, winning the trick in Z's hand with the queen of hearts. Z now leads the queen of spades. A discards the seven of hearts, and Y the six of diamonds. Z now leads the seven of spades. A discards the ten of hearts and Y trumps with the six of clubs. Y now leads the seven of clubs and B must discard. He cannot discard the jack of spades or Z's ten of spades will be good so is forced to discard the seven of diamonds. Z then discards the ten of spades. A must now discard. Fie cannot discard tlie jack of hearts or Y's eight of hearts will be good so A is forced to discard the ten of diamonds. Y then leads the eight of diamonds and Z's ace and deuce of diamonds are both good. Y Z thus win all of the tricks.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now