Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Value of Brain In Sport

Comments on the Importance of Intelligence in Baseball, Football and Boxing

W. O. McGEEHAN

IT is my notion that the brain in amateur sport is almost negligible, which is quite logical, for the object of amateur sport is to rest the brain. This, of course, does not apply to those amateur sportsmen who have acquired the professional attitude. It does not apply to intercollegiate football, where a victory is essential to the happiness of all concerned and where a defeat is a tragedy.

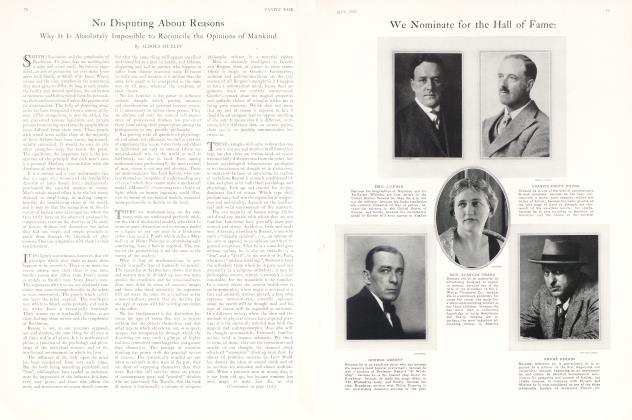

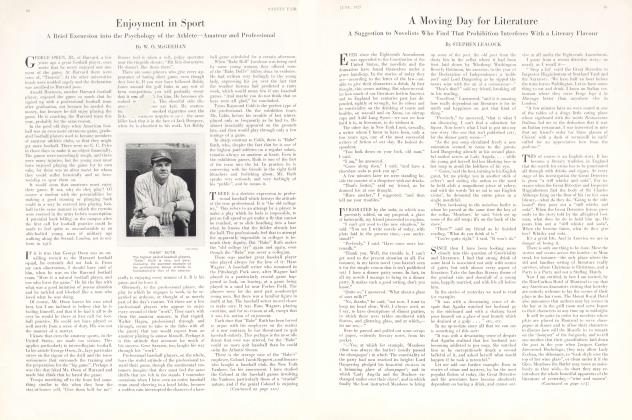

Naturally, it is in the national game of baseball that they find, and give greatest credit to, the power of mind over matter. When an American Rodin wants a model for his statue of The Thinker he will take the figure of a stout gentleman sitting on the player's bench with his chin in his hands peering out intently at the baseball diamond. This stout gentleman will be none other than Mr. John Joseph McGraw, manager of the New York Giants.

As one might say, you do not have to prove that Mr. John Joseph McGraw is the master mind of the National Pastime. Mr. McGraw has saved us the trouble by admitting this in no passive fashion. In his own memoirs he has acknowledged controlling practically every motion of all the players of his team during a World Series which they won in straight games.

Now this was not an afterthought, either. That dauntless egotist announced before the series started that he would do this. He told his pitchers that he would signal for every ball that was pitched. This announcement was carried in the public prints and the spectators noted that the Giant pitchers looked toward the dugout where the "Thinker" was squatted, before each ball pitched.

This was one of the series against the New York Yankees which the Giants won in five games, one of these being the tie game which was called on account of darkness while the sun was still bright and high above Coogan's Bluff, after which the inmates of the Polo Grounds raised such a storm of protest, that the entire proceeds for the day were given to charity to allay the popular indignation.

"Babe" Ruth of the Yankees had done very badly that series. In the last inning of the last game he stood at the plate feverishly anxious to redeem himself. Mr. McGraw admits that he had discovered his batting weakness up to that point and had been almost entirely instrumental in baffling him through his regular instructions to the Giant pitchers.

There were men on bases, enough of them to tie the score if "Babe" Ruth could hit that ball. There were two strikes on the "Babe." He had been too eager. The Giant pitcher was winding up. Suddenly Hughey Jennings, McGraw's lieutenant, dashed out of the dugout waving his arms and shouting. The pitcher paused in the midst of the wind-up and came over to first base to get his instructions.

Then he went back to the box and threw the ball. It struck in the grit in front of the plate but the over anxious Ruth swung at it and struck out, ending the game with one futile gesture.

"Yes," said McGraw afterward, "I told Hughey Jennings to tell the pitcher to throw that ball into the dirt. The pitcher wouldn't believe his instructions until 1 shook my fist at him. I was sure that Ruth would strike at the next one, no matter what it was, and he did."

This is just one vivid instance of the power of the master mind of baseball over matter in bulk, in the person of Mr. Ruth, whose movements at the bat arc simple and sincere. The great American game is one of guile, and by followers of cricket, might even be classed as one of low cunning. There arc those who will scoff at the notion of Mr. John Joseph McGraw controlling nine baseball players in action as though they were automata, but the results might indicate that there is quite as much truth as bombast in it.

McGraw has managed the Giants just twenty-five years, and in that time his club has won ten pennants and has been in second place ten times. The average tenure of a player with the Giants certainly is not more than five years, consequently these results have been attained with at least live different Giant teams. It could not all have been in the selection of the players. The greater part of it must be due to the manner in which they were handled.

In the beginning, baseball was a frank and simple enough game, but it quickly developed into a pastime where the entirely professional attitude predominated and where the idea was to win by any means and at any cost. Even in amateur games of baseball there is nothing of the amateur spirit. It does reflect the spirit of American life, as no other game reflects the spirit of its people.

McGraw's genius for the national game came to him, as they would say, naturally, but it was developed in the school of the old Orioles, of whom they will sing until there develops a scandal big enough to wreck the national pastime completely. This team contained a collection of baseball intellect but there was none on it the equal of McGraw's. Equipped with a keen eye and an uncanny memory, he was always a few jumps ahead of all the rest.

In contrast to the sustained "master minding" of John Joseph McGraw the one "bonehead play" pulled by Fred Merkle in the game between the Giants and the Chicago Cubs stands out. Now Merkle was a good baseball player, and far above the average of even the players of today in intelligence, but he will be remembered as the player who pulled the monumental and historical "bone."

It was not "boneheadedness", but the following of a custom. In the last inning Merkle drove out the hit that brought in the winning run. He darted down to first base, but instead of proceeding to second he sheered off and started for the clubhouse. In the meantime Johnny Evers of the Cubs ran down and seized the ball from an outfielder. He ran back and touched second, screaming at the umpires and waving his arms. In the meantime the crowds had surged into the field, joyous over the fact that the Giants had won and clinched another pennant. The Cubs protested and the protest was allowed. Merkle had forgotten to touch second. No player has since that time.

To this day when the name of Merkle is mentioned to the average baseball fan, he will say, "Oh yes. The man who pulled the bone."

Continued on page 126

Continued, from page 75

But the classic fit. of baseball aberration was the one which seized John Anderson, who stole second with the bases filled.

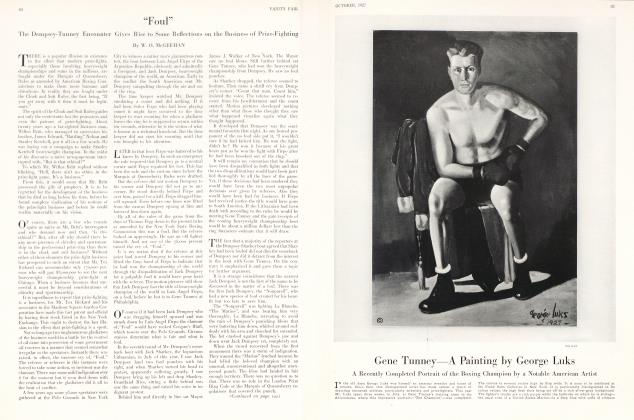

Mr. James J. Corbett, the eminent actor, author and former pugilist, is given credit for having first used brains in a sport where brains were previously regarded as almost superfluous, the sport with which the late Marquis of Queensbury was associated, namely, pugilism. Until the advent of Mr. Corbett, the equipment for a successful exponent of that art was entirely physical.

Corbett showed evidence of being able to do his own thinking, and with much rapidity, in one of his early fights, the battle on the barge with Joe Choynski, a brother Californian. When the bout was about to start it was discovered that there was but one pair of five ounce boxing gloves aboard.

"I'll take those," said Mr. Corbett. "And I will let him wear skin tight gloves." Choynski accepted the apparent advantage. The result was that Choynski sprained both hands, while the gloves protected Corbett's, and he won the fight.

It was in the championship fight with John L. Sullivan that Corbett revolutionized the technique of prizefighting in a single day. While the Marquis of Queensbury Rules had been accepted in fact they did not prevail in spirit. The notion of a fight was two men "toeing the scratch" as they did under the London Prize Ring Rules. Feinting and footwork were introduced by Corbett.

In vain did the adherents of the great John L. shout, "Stand and fight, you coward. This is not a footrace.' Corbett flitted around the ponderous John L. like a ghost, jabbing him and tantalizing him until Sullivan's sides began to heave, and the old gladiator panted like a weary old lion. In the end, Corbett, when he was sure that* Sullivan was utterly arm weary and spent, knocked him out.

Thus did brains, or what stand in lieu thereof, come to the prize ring.

I give Corbett credit for thinking out his campaign, but in most cases what is known as cleverness in the prize ring is merely a case of reflexes that are almost simian in their quickness.

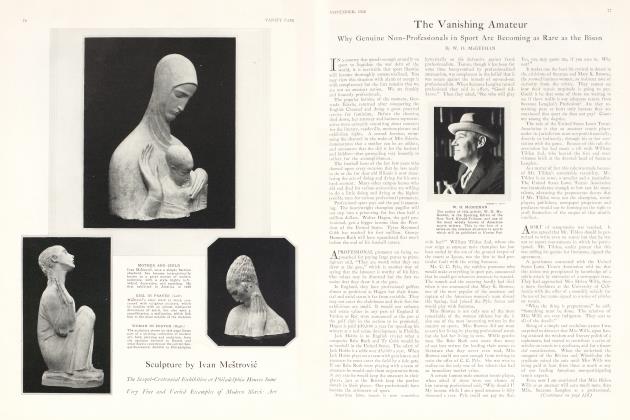

The present modest and retiring heavyweight champion is a thinker. It is my notion that he paved the way to the beating of Dempsey by that aeroplane trip from his training camp to Philadelphia. He had been making a study of Dempsey ever since he made up his mind to meet him for the Championship. He had read that when Dempsey took his first trip to Europe, he was awed by the notion of traveling on a steamer.

Tunney took that first aeroplane trip, though it made him ill, for the effect that it would have on his opponent. It was his bluff at being confident of victory and indifferent as to the reputation of Dempsey. It worked, for Dempsey heard about it, and Tunney's apparent indifference baffled the simple minded Dempsey quite as much as Tunney's right. The styles of fighting change with the champions.

Since the glamorous game of intercollegiate football was revolutionized by the opening up of play and the forward pass, the brain has been quite as much of a factor in this game as it has been in modern prizefighting since the adoption of the Marquis of Queensbury Rules. But always it is the brain of the professional coach. He controls his players as completely as Mr. John Joseph McGraw controls his baseball Giants.

Every year the All-America teams are made up and filed away in the archives, but the coaches remain, provided they can show enough victories to satisfy the insatiable alumni. Of all the coaches under the system of the open game, Mr. Knute Rockne of Notre Dame holds the most remarkable record.

It is reasonable to assume that the material collected each year by Rockne can not be more intelligent or more virile than that collected by any other college. Yet, year after year, the Rockne system of making football teams turns out squads that go wandering around the country, skipping from coast to coast and beating colleges with larger student bodies. They are not bulkier young men than the players of other teams, these men of Notre Dame, but they say of them that "they have football brains." One must conclude that these "brains" arc drilled into them by Rockne.

My theory is that the coaches of other teams were slower to recognize the change that was brought about by the opening up of the game, and that their sluggishness in this was due to the influence of the old grads, who were slow in becoming reconciled to the new game, which they called "mere basketball."

But, just as Corbett recognized the opportunities offered by the application of the Marquis of Queensbury Rules for an open and running attack, Rockne saw the chances of the new football, and grasped them. More than any other coach, Rockne has made the brain a factor in intercollegiate football.

The three "intellectuals" I have picked in sports, Corbett of the prize ring, McGraw of the diamond and Rockne of the gridiron, are quite distinct types. They have this in common. They are all three professionals with the one notion in all the games they play. They must win.

In considering the influence of the brain on amateur sports I questioned a writer who cares for nothing but amateur sport. I demanded to know instances where thinking had played a spectacular part In any amateur contest.

He thought a while. Then he said, "I hate to see you get away with that, but I can not think right now of any case where it has."

I do not mean to imply that the amateur sportsmen are not more intelligent on the whole than the professionals, but when a man is playing a game for the sake of play, he is not inclined to tax the brain or to resort to trickery to win. The very spirit of amateur sport seems to bar the use of the brain.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now