Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Menace to American Pugilism

W. O. McGEEHAN

A Complaint, in Retrospect, Based on the Treatment Accorded to Luis Angel Firpo in America

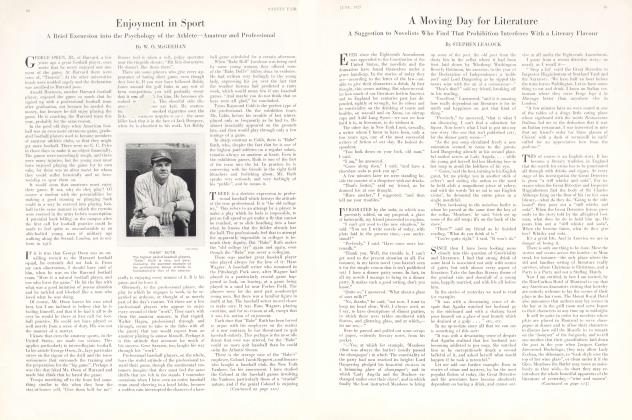

MORALLY, and even technically, Senor Luis Angel Firpo, of Argentina, is heavyweight champion of the world. The mantle of the late John L. Sullivan, which became somewhat soiled while in the possession of Jack Johnson, and which was worn in such indifferent fashion by Jess Willard, should rightfully be draped upon the shoulders of the gentleman from Buenos Ayres.

If Senor Firpo were an American prizefighter, with a vociferous American manager behind him, he would now be claiming the heavyweight title and receiving no little sympathy from the public at large. But Firpo has decided that it would not be a graceful gesture. The Latin has a horror of anything graceless.

According to the rules of the New York State Boxing Commission, Luis Angel Firpo became heavyweight champion of the world when he was fouled in the first round of his fight at the Polo Grounds. The rules of the Boxing Commission say clearly that to strike a man who is down constitutes a foul blow. In defining what it is to be down, the Commission has ruled that a man in the act of rising to his feet, after a knockdown, is to be considered down. Dempsey struck Firpo when he was rising to his feet in the first round; therefore, Dempsey should have been disqualified and Firpo should have been awarded the heavyweight championship of the world.

Of course, the consequences of the enforcement of this ruling would have been farreaching. Referee James Gallagher would have needed the protection of all the available constabulary to save him from the infuriated patriots at the ring-side, and public spirited citizens who consider that national prestige depends on our prestige in pugilism, would now be organizing expeditions to bring back Sullivan's mantle to the United States.

The clarion call would be sounded throughout the land for a contestant who would bring the heavyweight title back to the United States, lest our pugilistic prowess fall to the level of England's, whose representative is Joe Beckett, the most consistently horizontal fighter in the world. Beckett has been flattened so often and so thoroughly, that even George Bernard Shaw is depressed and thinks something ought to be done about it.

THE menace to the American pugilist has not been dispelled. On the contrary, it looms up more formidably than ever. Dempsey and Firpo will meet again. Their last encounter drew over a million dollars at the turnstiles,and as long as the memory of that swiftly moving melodrama lasts, the promoter of the next bout may write his own ticket. The Yale Bowl would not hold a tenth of those who would pay any price to see it, and consequently a second meeting of Dempsey and Firpo is inevitable.

The most patriotic of our prizefight experts admit that our hero, William Harrison Dempsey, got all of the breaks in that first clash, even overlooking the fact that he should have lost the fight on a technicality ignored by the referee. Had it not been for those breaks, the pride that the patriots take in him would have suffered a rude shock. Had it not been for the breaks at Waterloo, history might have been altered. Next time the breaks may be with Firpo. And the outcome is gravely uncertain. Let us consider break number one. Firpo, being a stranger in the country, did not know the American attitude towards the boxing authorities. He took seriously the Boxing Commission, presided over by William Muldoon, humorously known in local prize-fighting circles as the Duke of Muldoon because of the gravity with which he rules over his subjects.

Our own fighters take this body lightly, and believe that their rules do not mean much of anything. While the referee was instructing the men at the Polo Grounds, Dempsey listened impatiently—and probably heard nothing. No American fighter ever heeds those instructions. But Firpo listened attentively as the instructions were explained to him by the interpreter. He was impressed, and fearful of disobeying any of them, lest they might cause his disqualification.

The fight had not been in progress more than a few seconds when Gallagher, the referee, shouted something. Firpo, who knows little English, hearing the voice of the representative of the Boxing Commission, instinctively turned his head. At that instant Dempsey administered his celebrated right hook. Firpo went down for the first l ime. Now, if Firpo had not gone down for the first time, he might not have gone down at all.

That was the first break for Dempsey.

It was said, before the fight, and demonstrated during it, that Firpo was wide open for a left hook. By the same token, it was demonstrated that Dempsey, due to the style of fighting he adopted that night, was equally wide open for a right hook. Firpo has a right hook and he landed it. If that blow had landed on Dempsey's chin, the expeditions to bring the championship back to the United States would now be fitting out. But the blow landed on Dempsey's left eye, closing it. And that was the second break for the champion.

In a daze, Dempsey was forced against the ropes. His knees were sagging, his eyes glazing. Firpo was battering him down with those overhand right hooks. The crowd, sensing the staging of that most thrilling of all dramas, the passing of a heavyweight champion, surged towards the ring. One more right hand drive would do it, but Dempsey slipped through the ropes and out of the ring.

If Dempsey had not done so, he certainly would have been knocked out. His guard had dropped. His knees were shaking. Count that as break number three for the heavyweight champion.

Dempsey dropped into the arms of a friendly American expert, his legs kicking spasmodically at nothing. If he had fallen on his head from that high-pitched ring he never would have come back at all. "Get me back", he panted. The expert shoved him back into the ring. There is no rule in the articles drafted by the late Marquis of Queensberry to govern what should happen when a champion involuntarily makes his exit from the ring. This will go as break number four for Mr. Dempsey.

There was never a break for the invader. By the rules, Dempsey should have retired to a neutral corner every time he scored a knockdown. But Dempsey knew that the rules meant but little. Apparently, so did the referee. Or it might have been that the referee, who is supposed to follow the count of the timekeeper, could not watch Dempsey, the man on the mat, the timekeeper, and the seconds of both men at once. Argus himself might have had difficulty as a referee, remembering all the rules augmented and elaborated since the writing of the Marquis of Queensberry's twelve simple commandments.

Whenever Firpo fell, Dempsey was waiting behind him ready to drop him again. He was so conveniently close that once, after a knockdown, he had to leap over the prostrate Firpo to avoid falling over him. It was only after the last knockdown that Dempsey obeyed the injunction to retire to a neutral corner. He did it, then, because he knew that Firpo could not get up again. Dempsey, with the killer instinct of the true prize-fighter, has a sixth sense in the ring. It tells him when he has made his kill.

LET all of those who are so certain that the American is always superior to the foreigner, consider these things and prepare himself for what may be a shock of great magnitude at the second meeting. Let him also consider the character of Luis Angel Firpo, this young man who has accepted the title of "Wild Bull of the Pampas" as a graceful tribute from the people of the United States. Senor Firpo is not at all discouraged. Though he has said for publication that he was beaten fairly, he may not believe this to be true. Physically, he was not hurt by the knockout. George Bernard Shaw, who has personally never stopped a left hook to the chin, will tell you that no serious physical damage is done by a knockout punch.

The next time Firpo meets Jack Dempsey, he will take the Boxing Commission, William Muldoon and the rules, in the same humorous fashion that our American boxers take them. When the bell rings he will forget the Latin notion that he must do the graceful thing, and he will have in his corner a strident-voiced American manager who will remind the referee of a few of his manifold duties.

(Continued on page 118)

(Continued from page 55)

Firpo will carry into the ring that same self-confidence, self-reliance and self-will that brought him up fighting every time he was knocked down. lie knows that he can hit Dempsey hard enough to stun him. Next time he throws that overhand right hook in the direction of the champion, it might land on Dempsey's chin instead of his eye, for Dempsey will still be wide open for that right hook.

In view of the intense veneration for the mantle of the late Mr. Sullivan, one shudders to think of what might happen at the next Dempsey-Firpo bout; or what might have happened at the last, if the breaks had not gone to Dempsey or if the rules had been taken seriously. One observes the plight of England, once the dominating influence in the prize-ring, whose unofficial emblem used to be a clenched fist. Now, alas, it contains the recumbent figure of a boxer. Perhaps it would be little short of treason to picture the United States in such a position, but the menace is there,

One of the first questions shot at David Lloyd George as he was being received at the City Hall of New York by the Mayor's Committee of Welcome, was "Hey, Lloyd George, what's the matter with Joe Beckett?" Even the little giant himself looked embarrassed—and, so they say, a little sad.

Just now our dominion in the pugilistic world is supreme—in all classes. It is true that Pancho Villa, the flyweight champion who beat Jimmy Wilde, the last British title holder, is an American by way of the Philippines.

It is true that Giuseppe Carrora (Johnny Dundee), the featherweight champion, who won his title from Eugene Cr qui of France, was born in Italy. But he is an American citizen by naturalization.

This suggests a way of keeping the title in the United States, even if Firpo should knock out Dempsey at their next meeting, We could compel Firpo to go through with his intention of becoming an American citizen. We should preserve our pugilistic prestige even if we must preserve it by means of a technicality.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now