Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowEnjoyment in Sport

A Brief Excursion into the Psychology of the Athlete—Amateur and Professional

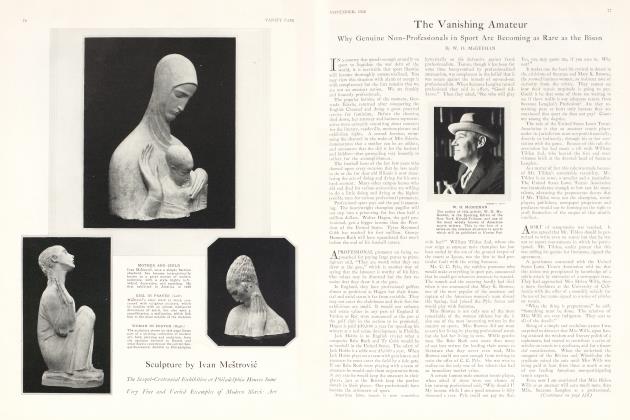

W. O. McGEEHAN

GEORGE OWEN, JR., of Harvard, a few years ago a great football player, once wrote that he never enjoyed one moment of the game. At Harvard there were cries of, "Treason". At the other universities heads were nodded sagely and the declaration was ascribed to Harvard pose.

Arnold Horween, another Harvard football player, enjoyed the game so much that he signed up with a professional football team after graduation, not because he needed the money, but because he did enjoy playing the game. He is coaching the Harvard team this year, probably for the same reason.

In the good old days when American football was an even more strenuous game, graduated football players used to become members of amateur athletic clubs, so that they might get more football. There were no C. C. Pyles in those days to make it an object financially. The games were exceedingly rough, and there were many injuries, but the young men must have enjoyed playing the game for its own sake, for there was no alma mater for whom they could suffer heroically and no heroworship to spur them on.

It would seem that amateurs must enjoy their game. If not, why do they play? Of course a student with the potentialities for making a good running or plunging back could in a way be coerced into playing football in the same manner in which the recruits were coerced in the army before conscription. A potential back lolling on the campus after the first call for football practice could be made to feel quite as uncomfortable as an able-bodied young man of military age walking along the Strand, London, not in uniform in 1915.

IF it is true that George Owen was an unwilling recruit to the Harvard football squad, he certainly did not look it. From my own observation, I should have said of him, when he was on the Harvard football team, "Here is a natural football player, and one who loves the game." He hit the line with what was a good imitation of joyous abandon and he tackled and blocked like a man who loved what he was doing.

Of course, Mr. Owen knows his own mind best, but I am inclined to believe that lie is fooling himself, and that if he had it all to do over he would be there at first call for football practice. He could not have played so well merely from a sense of duty. His was not the manner of a martyr.

I know that, even the amateur sports, in the United States, are made too serious. I bis applies particularly to intercollegiate football. In bis article George Owen, Jr., lays particular stress on the rigour of the drill and the tense seriousness that surrounds the training and the preparation for the "big game". Perhaps it was this that irked Mr. Owen of Harvard and made him think that he hated the game.

Troops marching off to the front feel something similar to this when they hear the stay-at-homes yell, "Give them hell for me". Boxers feel it when a soft, pulpy spectator near the ringside shouts: "Hit him downstairs. He doesn't like them there".

There are some players who give every appearance of hating their game, even though they love it. If you ever have followed Bobby Jones around the golf links in any sort of keen competition, you will probably swear that it was all ??? for him. He becomes absorbed in ???y. The cheerful side disapp ??? are knit. He scatters hu??? smoked cigarettes over the links ??? features acquire some ??? the same killer look that is in the face of Jack Dempsey, when he is absorbed in his work. Act Bobby really is enjoying every minute of it. It is bis game, and he loves it.

Obviously, to the professional player, the play in which he engages is work, to be regarded as arduous, or thought of as merely part of the day's routine. Yet there are a few professional players who appear to enjoy every second of their "work". They carry with them the amateur manner, in that regard. Walter Hagen, professional through and through, seems to take to the links with all the gayety that you would expect from an amateur playing to amuse himself. Perhaps it is this attitude that accounts for much of his success. Gene Sarazen, too, laughs his way through his "work".

Professional baseball players, on the whole, have the stolid attitude of the professional toward their game, though the sentimental customers imagine that they must feel the same thrills that are felt in the stands. I remember occasions when I have seen an entire baseball team stand cheering in a hotel lobby, because a sudden rain interrupted the chances of a baseball game scheduled for a certain afternoon.

When "Baby Doll" Jacobson was being sued by some young woman, they offered some of the "Baby Doll's" billets doux in evidence. He had written very feelingly to the young lady, expressing his joy over the fact that the weather bureau had predicted a rainy week, which would mean few if any baseball games. "And maybe you do not think that us boys were all glad," he concluded.

Tyrus Raymond Cobb is the perfect type of the professional. On the exhibition tours, Mr. Cobb, before his trouble of last winter, played only as frequently as he had to. He almost invariably appeared on the grounds late, and then would play through only a few innings of a game.

In sharp contrast to Cobb, there is "Babe" Ruth, who, despite the fact that he is one of the highest paid athletes on a regular salary, remains always an amateur at heart. Even in the exhibition games, Ruth is one of the first of the team into the lot. In practice he is conversing with his friends in the right field bleachers and frolicking about. Mr. Ruth speaks very seriously and very feelingly of his "public", and he means it.

THERE is a derisive expression in professional baseball which betrays the attitude of the true professional. It is "the old college try." This refers to an attempt by a player to make a play which he feels is impossible, to put on full speed to get under a fly that cannot be reached, or to slide headlong into a base when he knows that the fielder already has the ball. The professionals feel that to attempt the apparently impossible in colleges is beneath their dignity. But "Babe" Ruth makes the "old college try" again and again, even though the "Babe" was never a collegian.

There was another great baseball player who played always for the love of it: Hans Wagner. A baseball writer who remained in the Pittsburgh Park once, after Wagner had played in a particularly crucial game happened to look, on leaving, at a game being played in a sand lot near Forbes Field. The players were for the most part nondescript young men. But there was a familiar figure in mufti at bat. The baseball writer moved closer to make sure. It was Hans Wagner, playing overtime, and for no reason at all, except that it was his notion of enjoyment.

Each time that "Babe" Ruth has been forced to argue with his employers on the matter of a new contract, he has threatened to quit baseball entirely. This perhaps is the most idle threat that ever was uttered, for the "Babe" could no more quit baseball than he could swim the Atlantic Ocean.

There is the strange case of the "Babe's" employer, Colonel Jacob Ruppert, a millionaire who bought a baseball club, the New York Yankees, for his amusement. I have studied the Colonel at the baseball games involving the Yankees, particularly those of a "crucial" nature, and if the genial Colonel is enjoying himself, so is the leading man at an electrocution.

(Continued on page 110)

(Continued from page 66)

I recall one particular game, which meant a pennant if it was won. For a few innings the Yankees were leading. Then the pitcher went had, and the score was tied. There was a low moan of anguish. Colonel Ruppert dashed out of his box and fled beneath the stands. He stood there for a minute until he heard the crack of a hat. Then he dashed into the clubhouse and locked himself in his private office.

Half an hour later he heard the tumult and the shouting. He opened the door of his office fearfully, and asked of one of the attendants, "Who won?" A little while later the Colonel, receiving congratulations on the first Yankee pennant, remarked, "Lord, how I enjoyed that baseball game." There are circumstances it seems, under which it is not necessary to see a baseball game in order to enjoy it.

There are few prizefighters eloquent enough to describe their real emotions in the ring, and if they could, they would not tell them for trade reasons. It is my notion that Jack Dempsey enjoys fighting, and that he has the instinct and the urge of the game too strongly for it to he checked by the knowledge that it is highly lucrative work.

On the other hand, it seems that the game goes entirely against the finer grain of his conqueror, Gene Tunney, the young man with the face of a zealous young Irish priest and the gentle voice and manner. And yet 1 wonder. When the fighting time comes there is not a more sell-possessed or more serenely confident gladiator than this same soft-spoken Gene Tunney.

To return to football for a moment: In spite of Mr. George Owen, Jr., I am certain that the average college football player enjoys his game, and in spite of the seriousness with which the old grads have surrounded it. There was an incident in the older and rougher day where an opposing Harvard and Princeton line man used what is called "unnecessary roughness" all through the game. It was done by mutual agreement and the referee was intentionally blind. At the end of the game the pair, limping and with their faces terribly battered, walked off the field with their arms around one another's necks. They had enjoyed themselves thoroughly, or so it seemed.

Some of the enjoyment of sport, perhaps, is based on the psychology evolved by the half wilted boy who, when he was remonstrated with for hitting himself on the head for long periods with a hammer, explained, "I am doing it because it feels so good when I stop."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now