Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Nowsemi-professional

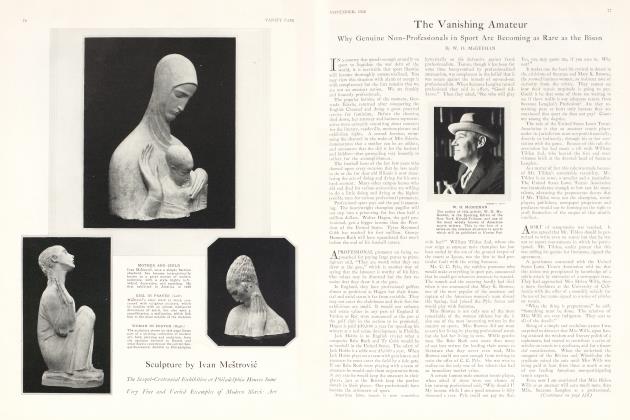

BYW. O. MCGEEHAN

why intercollegiate football should no longer be considered as an amateur sport

Intercollegiate football, said to be the only sport where amateurism is not questioned, rapidly is becoming only half amateur. From some points of view it is on the way to becoming less than half of one percent amateur.

One of the chief arguments in favour of the maintenance of this sport is that it instills initiative into the players and trains them to quick thinking in emergency. It should, hut the initiative in football is being taken away from the players by the coaches.

At Carnegie Tech and at several of the western colleges the players are not even permitted to elect their own captains. The field leaders of the football teams are appointed by the coaches. This is another indication of the seriousness with which the colleges are taking the game.

There have been times when militia regiments have been mustered into the service in time of emergency with officers elected by the enlisted men. The War Department found it necessary to replace the elected officers by men from the regular army. No doubt it was necessary, but are intercollegiate football games wars? It begins to look as though some of the colleges had begun to regard them as seriously, if not more seriously, than wars.

Of course the coaches, who have insisted on appointing captains of their own choice for their football teams will supply all sorts of arguments to show that it is logical and necessary. For instance there have been occasions when a player elected captain of the football team did not have the qualifications to make the team in the opinion of the coach and it is quite evident that the opinion of the coach is final. The coach started as a drill master. Today he is the commander-in-chief of football for whatever college employs him.

In the primitive days of intercollegiate football the captain of the football team would say to the coach, "This is our football team. Coach it." Now the football coach says to the chairman of the football committee and some of the more influential alumni, "Is this the best material you could get? Oh well, I will do the best that I can with it."

The football coach can defend this position. As long as a football coach can produce winning football teams he has steady employment. When he cannot, because of poor material, or because he has become somewhat passe, then the old grads start clamouring for his job and when the old grads clamour for a coach's job, they get it.

Therefore the coach demands more and more power. He says, in effect, "You want winning football teams? Then you must let me take full charge if you want me to take the full responsibility." And this seems to sound reasonable enough from the point of view of the coach and of the old grads.

If you are going to hold a man responsible for the success or failure of a business it is only fair that he be allowed to select his subordinate officers or officer. And more and more intercollegiate football seems to become a business.

In some of the colleges the receipts from football would run the institution. Also football affects to a certain extent the prestige of the college. Colleges need publicity and the widest publicity seems to come through a successful football team.

A decade or so ago the University of Notre Dame hardly was heard of and until Mr. Edward F. ("Chick") Meehan became football coach of New York University the rest of the country did not know that there was such an institution. At the current writing they are well aware of it, especially during the football season.

Intercollegiate football has become a big business and a serious business. The annual returns from a number of the colleges indicate that the proceeds from football support all of the other sports in the colleges. Few colleges have athletic funds. They must get them out of gate receipts and football is the only sport that produces certain profits. That is, of course, if the football teams are of the first order.

I recall that a few years ago the University of Dubuque decided to abandon the football team. The president described all of the evils attributed to the game, spoke of over-emphasis and of the exalting of the gladiatorial spirit and all of that sort of thing. He concluded his statement by observing, "And also the football team showed a deficit." The last reason was sufficient. The rest did not matter.

The financial returns of the University of California for the football season last year indicate just how big the intercollegiate football business has become. The University of California, having one of the largest stadia in the country drew more spectators for football games than any other college in the country. This team played ten games. The average professional baseball club plays 154 games in a season. The report of the University of California shows that their football team drew bigger gate receipts in a ten game season than many of the big league baseball teams in a season of 154 games.

Of course to do this the University of California had to have a strong football team, a well coached football team and a successful team. They had all of this. If they had not, there would not be that amount ingate receipts. They love their coach because he produced a good football team and enhanced the prestige of the University of California. Probably they would not demur if he indicated that it would be best for him to appoint the football captains.

Intercollegiate football became what might be called semi-professional years ago. It is known that the professional coaches with their staffs direct the movements of their football teams on the field just as a general in his field headquarters directs the movements of his troops in action.

Or to get away from the serious simile one might say that they direct .their teams as John J. McGraw and Wilbert Robinson direct their baseball teams from the bench. The football coaches direct amateur players while the baseball managers direct professional players. That is why I would call intercollegiate football a semi-professional game. The brawn, the spirit and the speed may be amateur but the strategy, the brains and the initiative are thoroughly professional.

Some football coaches have a series of signals fashioned after the signals used in professional baseball by the managers. Others are content with watching and sensing a weakness in the defense or poor judgment on the offense. Then a man is drawn from the front line and a substitute is sent in with orders from the General Headquarters.

They made a gesture to stop this sort of thing by ruling that a substitute should hold no conversation with the rest of his team until one play had been run off. But substitutes frequently are rushed in for purposes other than replacing an injured player.

There was that incident in the last ArmyNotre Dame game. An O'Brien was sent in to replace one of the Notre Dame ends. This O'Brien had one talent. He could catch a forward pass at top speed. Naturally when Knute Rockne sent in O'Brien at this point in the conflict, the Notre Dame quarterback, unless he happened to be very dumb indeed, could catch the hint. And no Notre Dame quarterbacks are dumb. Mr. Rockne does not tolerate dumbness.

On the next play O'Brien dashed forward and crossed to the corner of the field near the Army line.

Continued on page 114

Continued from page 83

The Army was not paying much attention to him. A forward pass shot in his direction and O'Brien caught if on the run over his shoulder and shot across the line for a touchdown. That was his day's work. He was taken out.

It was that touchdown that won the game for Notre Dame. The strategy was all Rockne's, of course. In the game that is supposed to develop initiative, the coach has the initiative.

There have been sporadic efforts to prevent the direction of the team in the field by the professional coach.

I remember one meeting of the football coaches where T. A. D. Jones, former coach of Yale and now a sort of overlord of Yale football, rose to suggest the doing away with this quite well established practice.

"Let us agree to let the teams run themselves in the field," proposed Mr. Jones. "I for one am quite willing if the rest of you are."

There was an eloquent silence, indicating that Mr. Jones was quite alone in this matter.

Then up rose Gil Dobie of Cornell. He for one never would agree to such a proposal. If he did, he would be negligent in his duty to the university that employed him. Mr. Jones seemed to feel, he indicated, that football was a mere game.

The coaches have wThat seems like a sound argument for directing the matter of substitutions. A player might he hurt seriously and insist upon playing for the glory of the alma mater and thus become even more seriously injured. On that score the coach or somebody equally responsible should have charge of the matter of substitutions to that extent. But then how are you to prevent the substitute from becoming a courier from General Headquarters?

Somebody has suggested that the only -way of preventing the coaches from running the teams would be to keep them out of the stadium. Yet I do not think that there is any demand from the colleges themselves or from the old grads that the football players be permitted to play their game and to develop initiative. Colleges with a fair percentage of victories are quite content with the present system.

Only this, it is a bit far-fetched to insist that intercollegiate football develops initiative when all of the initiative comes from the professional coach. The brain is professional, the brawn is amateur. Since it is insisted that the brain plays a major part in the game, then intercollegiate football would seem to be more professional than amateur.

Or let us be generous and say that intercollegiate football as it is conducted to-day is semi-professional.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now