Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

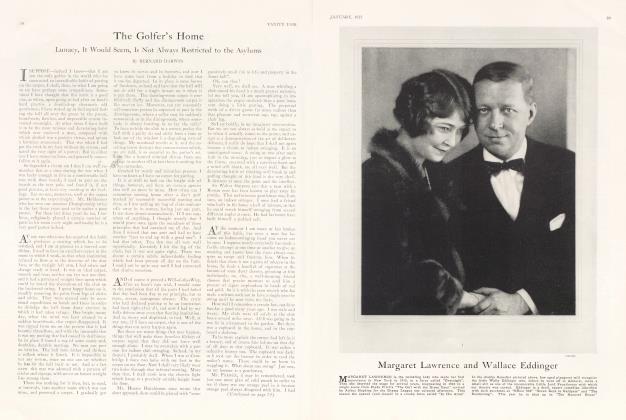

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA Sower of Golfing Seed

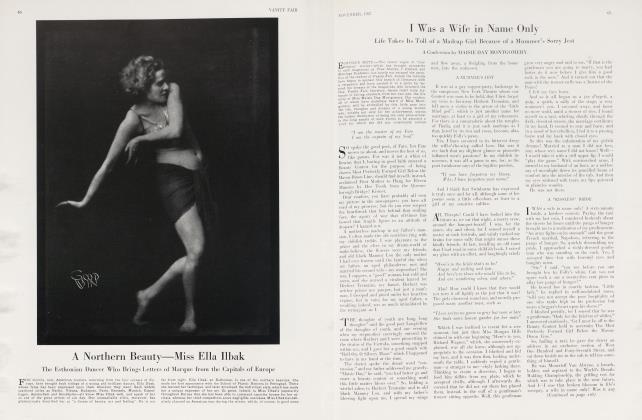

Notes on the Grand Old Man of American Golf—Walter J. Travis—and His Influence

BERNARD DARWIN

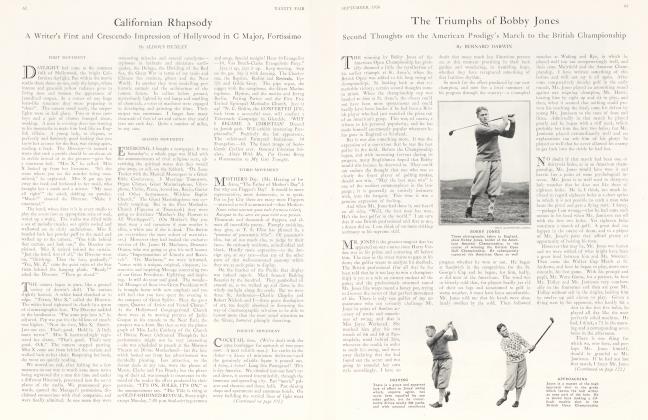

THE late Mr. Walter Travis will go down to golfing history as the first great American golfer; not American born, since he came from Australia, hut, from a golfing point of view, entirely American bred. He was also the first golfing conqueror of Britain. Mr. Ouimet was the second when he heat Ray and Vardon at Brookline; Jock Hutchison must he set down, I suppose, as the third though British horn and after him we have got thoroughly used to invading conquerors. Mr. Travis however was the first, eight years earlier than his next successor, and so perhaps it may he permissible for a Briton to try to trace his influence on American golf.

I do not think it is fantastic to suggest that he had a great and far reaching influence, even if it was necessarily an indirect one. As a man he was not at all typical of American golfers as we know them. There was about him something of dourness and of—I will not call it unfriendliness, hut of unresponsiveness, of a desire to go on his own way without paying very much attention to anybody else, which is the very reverse of what we have learned to expect from our always welcome invaders. But as a golfer, in the actual playing of the game, He seems to me to have had all the virtues which we over here come enviously to regard as typically American. If that he so, then I think that he should he credited with sowing at least some of the seeds of those virtues.

THERE never was a more painstaking golfer than Mr. Travis was, nor one who more earnestly applied an extremely shrewd intellect to mastering the game. It would he fanciful to attribute to his example the painstaking attitude of mind of his successors, because it is part of the American character to try to play a game as well as it possibly can he played and to live laborious days in the attempt. It is rather in details than in the general point of view that I should trace Mr. Travis' influence. He was, for example, a mighty practise!-. I should doubt if any man ever gave up more hours—and probably very happy hours—to solitary practise. The nearest approach to him here was Mr. Allan Macfie who won the British Amateur Championship in the 'Eighties.

He was a player something after Mr. Travis' type in that he did not begin the game a: a boy and, being light and small, had to depend on accuracy rather than strength of hitting. Day after day He would practise at Hoylake, going on and on though darkness was coming on. Whenever the caddies arrived in the morning to find the links dotted here and there with derelict golf halls, they would say, "Mr. Macfie was out last night". I do not know if Mi. Travis played in the dark hut he was a practise!of that frame of mind, who would go on and on, regardless of all surrounding circumstances, until In could get the thing just right. It was typical of him that when he first came to Sandwich, the scene of his victory in 1904 he began by merely walking round the links without playing a round, merely storing his mind with its characteristics and playing a shot now and then, as the spirit moved him, till he began to feel that he was getting that indefinable thing called the touch of the course.

He set an example, in practising, which all American golfers have followed ever since. Whether they are playing well and are confident or are playing ill and trying to discover the reason, they practise and I have no manner of doubt that they play the better for it.

A friend of mine, who has been a good deal in America, defined to me, as I thought rather well, the difference in point of view between the two countries in this matter. The Englishman, if he goes out to practise at all, will stop as soon as he has hit a few satisfactory shots for, he says to himself, "If I go on I may lose it or I may grow stale or at any rate I may waste some good shots, of which I cannot make more than a certain number". The American on the other hand thinks that the moment of having hit some good shots is the very moment for going on for, he says, "Now that I have got it I will make sure of not forgetting it and will learn to keep it for ever".

So much for practising. Now for another and more important point. Mr. Travis was, as I said, light and small and so to rely on accuracy may, in his particular case, have been to some extent making a virtue of necessity. Be that as it may, he did thoroughly appreciate the value of accuracy and he further appreciated the fact that permanent accuracy can only come from the true swinging of the club. Personally 1 have never seen a golfer who so well exemplified the value of a true swing. One or two of his spoon shots, played through a stiff cross wind, in that historic final at Sandwich, still remain astonishingly clear cut in my memory after twenty three years. As a famous old cricketing professional said of some heroic stroke at cricket, they "ought to have been picked up, put together again and kept in a glass case". The distance was such that any self-respecting British golfer would then have thought shame not to cover it with an iron, but Mr. Travis, with that easy, true swing of a spoon, somehow got nearer to the hole.

MR. TRAVIS was not a long driver; he even appeared a short one until there was anything particular to carry when he always seemed to have a little something up his sleeve. The American golfers of today, young, strong men who have swung a club from their boyhood, are long drivers. But they get their length by trusting to the true swing of the club. Of course they hit hard also hut the swing is the thing and they talk of swinging at the ball and not of hitting at it. Of all the good American players that I have watched, some naturally swing faster than others. Mr. Von Elm for instance, is a comparatively quick swinger, if set beside Mr. Bobby Jones, with his almost lazy take-back of the club; but I cannot think of any who can ever be said to hurry the swing. Everybody must, in crucial moments, occasionally go too quick at the ball, but it is a vice that the American golfer has subdued as far as it is in human nature to do so.

And then to come to my third point, Mr. Travis was a great putter. I suppose he had a natural talent for putting, but if he had he certainly never subscribed to that destructive aphorism which laid down that putting was an inspiration. He "tried out" every conceivable method and he realised that in putting perhaps more than in any other stroke of the game, rhythm is the most important thing. It is impossible to imagine a more smooth and flowing, almost poetical movement of the club than that of Mr. Travis' putter—it did not seem to hit the ball so much as to pass through it, as through some soft and unresisting substance. In this respect I am sure he had an influence on his successors and especially upon one of. them and that the greatest.

When first Mr. Bobby Jones came here—at Hoylake in 1921—he was not a conspicuously good putter and his method was not a noticeably convincing one. Then, as I have been told, at any rate, he had a conversation with Mr. Travis, who made him, so to speak, oppose the two wrists to one another, pushing the club back with the left and doing the actual hitting with the right. Certainly the next time we saw Mr. Jones here he had become a much better putter, with a more flowing and rhythmic manner, and this year at St. Andrews his putting was truly magnificent; he was, humanly speaking, always up, he was always straight and the movement of his club was the very poetry of motion. At the very first hole of the first round he hit his approach putt with something of a jerk. He got his four hut was evidently dissatisfied, for he filled up the interval of waiting before the next tee shot by practising with his putter. Mr. Hilton, who was standing by me in the crowd,shrewdly remarked, "That first one was a nervous putt—he's trying to recover his rhythm." He certainly did recover it for he holed a beauty at the very next hole and never lost his touch again. If Mr. Jones is the greatest golfer that has yet existed—and I am inclined to think he is—he owes it to the fact that his play on the green is as good as his play up to the green; and of that merit he probably owes some fraction at least to Mr. Travis.

Continued on page 124

Continued from page 88

To write about Mr. Travis is of course to recall that scene at Sandwich three and twenty years ago. To an impartial spectator I think it must have been a maliciously amusing one. As long putt after long putt dropped in and hole after hole was added to the American lead, the hitter consternation that fell upon the spectators, their faces growing every moment longer and longer, must have been essentially laughable. I think I have seen as good putting since that day hut I never have seen any that appeared so obviously bewitched. There really was something unhallowed, something of the black art about it and Mr. Travis, silent and inscrutable, standing motionless and watching the hall as it fell in, looked to perfection the wizard's part.

Within the next week we were all trying to buy, beg. borrow or steal a Schenectady putter, to see if any of the magic was in the club. I found my old one by chance, the other day, almost on the very day of Mr. Travis' death, at the bottom of a chest where the dust of ages lay thick. When I took it out a young golfer and golferess of seventeen and eighteen respectively asked what this strange thing was, the like of which they had never seen before—so I told them about that match at Sandwich and its hero and that, in turn, has set me writing about him.

Another stout virtue in Mr. Travis' make-up as a golfer was his extraordinary accuracy. I am sure that a great deal must have been written on this point since his death. A few records and instances to prove his consistency were recently included in a fine article on him by Grantland Rice in The American Golfer.

Mr. Rice mentioned the following achievements. In a memorable match at the old Westchester Country Club Mr. Travis hit the direction pole three times on a single round and missed it only by inches on two other shots. Playing in a 36 hole match at Garden City with Mr. "Snake" Ames (a figure in American sport) Mr. Travis registered the following score: 36-3636-36. In this match he had exactly par on 34 of the 36 holes played.

The second hole at Garden City is a short pitch over a ravine. Playing that course on six consecutive afternoons, Mr. Travis scored a 2 at this hole on each of the six consecutive days. At the age of sixty he scored a 66 and a 68 in one of the Florida championships, while at the age of sixty-four he played Garden City in 73, even par, and just two strokes worse than the then record of the course.

It was Mr. Travis who devised the expedient of smaller holes for practise purposes at Garden City—holes only a trifle larger than the ball itself. With such holes he practised for hours, his theory evidently being that if you can drop the ball into a two-inch cup, a four-inch cup will offer you no difficulties at all.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now