Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Case of Oscar Slater

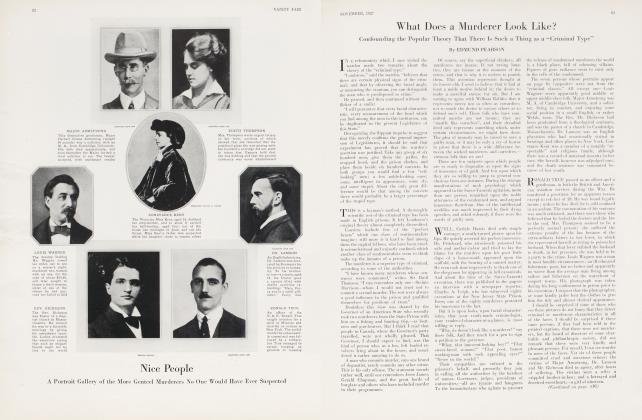

Relating What Is Perhaps One of the Few Unjust Convictions on Record for Murder

EDMUND PEARSON

"DON'T twit the Americans too much about the mote in their eyes of the Sacco and Vanzetti case, when we have in our own eyes the beam of the Slater case."

This was the advice of some English writers, when British and European publicists, with the smallest knowledge of the facts, were advising the Governor of Massachusetts how he could save the honour of his own State.

Not many Americans have ever heard, or remember much, about Oscar Slater. A few may recall that Sir Arthur Conan Doyle once wrote something about him. With the publication in this country of the Slater trial and the recurrence of the topic through a new book in Scotland, the fate of this unfortunate German Jew again becomes news.

It has never lost its interest for those who enjoy mysteries; nor for generous hearts which abominate injustice. Merely as a puzzle, it was one of the most peculiar of all murders, and in one respect, it resembles the American cause celèbre, the Borden case. That is because the murderer slipped through such narrow crevices of time and space, and vanished—as many think—into darkness.

IN 1908, Marion Gilchrist of Glasgow was eighty-two years of age. She lived alone, with a servant, a girl of twenty-one, in a comfortable apartment, on the second floor of a house in a good street. Her friends and callers were few; her relatives not many, nor was she on the best of terms with them. Miss Gilchrist owned and hoarded jewels worth no less than £30000. She could have seldom worn them; she went out but little. They were not heirlooms, but her own purchases, and they were to her a source of dreadful anxiety. She took precautions against burglars, by means of locks, bars and bolts. The street door opened by a contrivance upstairs, and Miss Gilchrist, on the rare occasions when she was alone, was fanatically cautious about admitting anybody. The servant, Helen Lambie, had her afternoon out; but was otherwise seldom absent except at one fixed time. This was at seven in the evening, when she went out for a very few minutes to do errands in the neighborhood, and to buy her mistress an evening newspaper. Still further to guard herself and her jewels, Miss Gilchrist had an understanding with the family below, (the flat above was empty) that if at any time she was heard to knock on the floor, they were to rush to the rescue.

Three nights before Christmas Eve, Helen Lambie went out as usual, leaving Miss Gilchrist peaceably reading a magazine before the dining room fire. A few minutes later, the Adams family, who lived below, heard a noise, a fall, and then three sharp knocks on the floor. Miss Adams advised her brother to go up without delay, and he did so. The door of Miss Gilchrist's flat was closed, and he rang the bell three times. At that moment he heard a sound inside, as if someone were breaking kindling wood. Actually, it was the murderer at work. Mr. Adams supposed that the servant was there, and after a moment or two went back to his own dwelling. His sister, who had heard further sounds, made him go upstairs again, and at the Gilchrist door he was now joined by Helen Lambie who had just entered from the street. They spoke together, and the girl opened the door of the flat by means of her keys. Almost as soon as they were inside, a man appeared from the bedroom door, walked up to them quietly and pleasantly enough, then suddenly darted by Mr. Adams, bolted down the stairs "like greased lightning", and disappeared into the dark street.

When the neighbor and the servant went into the dining-room, Miss Gilchrist lay on the hearth rug, her head horribly battered in. She was still breathing, but she died in a few moments,—of course, without speaking. Thus the sounds of the attack were heard by a man standing within a few feet; the murderer was almost caught in the act; and he walked up to two witnesses and passed them so near that one at least, could have touched him. The light, however, was dim; a single gas-jet, turned down. It is plain that neither witness suspected anything especially amiss when the stranger appeared; his friendly manner allayed their uneasiness; the whole incident was over in a second or two; and neither of them got any distinct impression of the man, aside from a few generalities which would be true for ten thousand men. Although the bedroom had been hastily ransacked, it was never clearly established that any robbery had taken place. Rings, a bracelet and a gold watch had not been disturbed, but Lambie thought that a diamond brooch was missing. On the description of this brooch, and the vague particulars about the fleeing man, the Glasgow police set to work.

For a few days they were all at sea. Then they learned that a diamond brooch had been pawned by a man called Oscar Slater, a not especially reputable but non-criminal person of varied occupation. He "was a dentist who dealt in jewelry". Search for this man led to the discovery that on December 26, five days after the murder, he had sailed from Liverpool to New York on the Lusitania; that he was accompanied by a woman; and that they shipped as "Mr. and Mrs. Otto Sando". This was certainly suspicious enough; but when Slater was arrested, on his arrival in New York, the case against him blew up. The whole thing hinged on the diamond brooch; except for that the police would never have heard of Slater. But almost the first thing which was discovered was that the brooch, pawned by Slater, was incontestably his own property; was unlike Miss Gilchrist's; and had been in Slater's possession months before the murder.

NEVERTHELESS, the prosecution was continued. He had fled from Glasgow, said the police. He had not, said Slater; he took his time about it, and was in no haste. He went under an assumed name, said the police. Yes, he did, said Slater; but it was because of his illicit relations with Mile. Andree Antoine, his companion, and their desire to avoid pursuit or persecution by the real Mrs. Slater, from whom the prisoner was separated. Well, said the police, he was the man seen leaving Miss Gilchrist's flat, on that night, and also lurking about the neighborhood, for days before that. And they produced witnesses.

God save us from such witnesses! Mr. Adams, Helen Lambie, and a little Meddlesome Matty of a girl, named Mary Barrowman, fifteen years old (when girls are most pestiferous) had crossed the ocean and testified at the extradition proceedings. Mr. Adams, educated and honest, could only swear that Slater "resembled very much" the man who had rushed by him in the dark hall. But Lambie and Barrowman gave testimony, doubtful in New York, but growing stronger and stronger all the time, till it became rockribbed at the trial in Edinburgh. Slater determined to go back and face trial in Scotland, —little doubting that he could establish the innocence which he constantly protested. He was a German Jew, speaking broken English, and not apt, when the circumstances of his life were known, to make the best of impressions. He had been in New York once before, —for a while as manager of a "social club" (a gaming club) on Sixth Avenue.

At the trial in Edinburgh, Slater's alibi was not perfect; neither was it overthrownThe prosecution had to depend largely on the testimony of Mary Barrowman, who swore positively that she recognized the prisoner as the man who rushed; past her in the street at top speed, at seven o'clock, on a dark December night. It must be remembered that in a Scottish Court the jury numbers fifteen; a majority decides; and a verdict of "not proven" is permitted. Slater's jury were out over an hour. By a majority they found him guilty. Nine voted "guilty"; five voted "not proven"; and one voted "not guilty". Had two of the jurors who voted guilty changed their votes, Slater would have been set free. In England or in America, it would have been a mis-trial.

(Continued on page 108)

(Continued from page 65)

While the prisoner was being sentenced to death he cried out piteously:

"I know nothing about the affair!"

Again and again, he protested that until he reached New York he had not known there was such a person in the world as Miss Gilchrist. The police never showed any connection between the two, nor how Slater could have known of Miss Gilchrist and her jewels, nor any method by which he could have entered the locked house.

The case differs from that of SaccoVanzetti, of course, by the fact that not all the jury were convinced of his guilt, and that the executive and reviewing authorities showed their doubts about the verdict by their action,—unsatisfactory as it was. The gallows was being set up, when the King's Ministers commuted the sentence to imprisonment for life.

Slater went to prison,—where he is today. The usual term of a life sentence in Great Britain is fifteen years; they are more lenient than we in America, where, in some instances, at all events, a life sentence is what the words indicate.

We are likely to hear more of Oscar Slater. Sir Conan Doyle, and many others, are firmly convinced that he has been cruelly wronged. So is William Park, a Glasgow journalist, the ingenious author of a recent book on the case. Still more impressive is the extensive history of the case, by the editor of the trial, Mr. Roughead. His position called for impartiality; he presents the case without argument, but says that if the evidence at the inquiry had been before the jury, Slater would have been given the benefit of the doubt.

An exceptionally able lieutenant of the Glasgow police suffered dismissal and punishment for his belief in Slater's innocence. He formed a plausible theory of the crime, and one which fits in with the idea that Helen Lambie had more than a suspicion of the identity of the murderer. According to this theory, the assassin was not a stranger, as was Slater, to Miss Gilchrist. He must have been admitted by her. The visit was for the purpose of procuring or destroying some document, and there was no robbery of jewels. The murder was not premeditated, but came as the result of a sudden quarrel. He killed; he made his lucky escape; he dived into the gloom of the Glasgow street; the police fished about, and by an extraordinary set of chances caught somebody quite different; an obscure little gambler and trader who had never in his life seen Marion Gilchrist!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now