Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Constant Nymph

DONALD FREEMAN

A Report on the Current Dramatization of Margaret Kennedy's Successful Novel

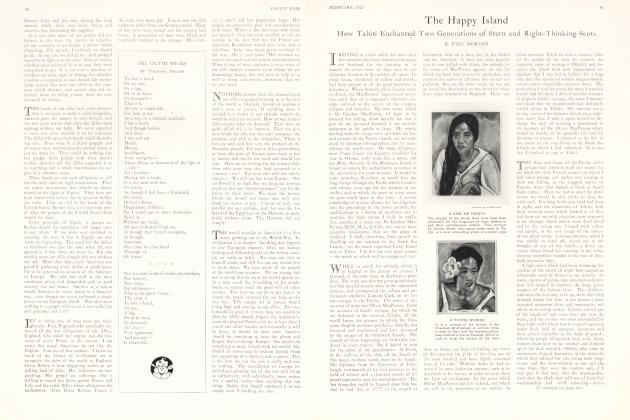

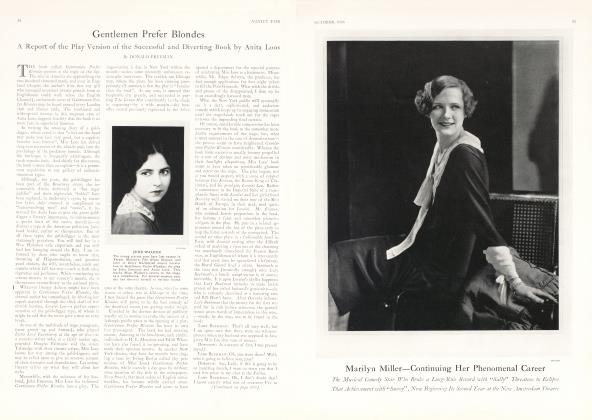

AFTER much preliminary heralding, the dramatized version of Margaret Kennedy's amazingly popular novel The Constant Nymfh has at last arrived upon the New York stage. It has not, I regret to say, taken the city precisely by storm. This may seem strange in face of the fact that London estimated this work highly when, with Edna Best as Tessa and the incredible Noel Coward as Lewis Dodd, the play was produced last season, in the British capital, and subsequently classified by the English critics as a very able concoction. This seemingly irreconcilable difference in international critical opinion may be better understood when I testify that Mr. Basil Dean, the English stage director, had his hand in the proceedings. More of him, however, later.

Miss Kennedy's excellent novel has been translated into terms of the theatre by the author herself and the aforesaid Mr. Basil Dean with much fidelity to the original. Hence, any criticism of the play must unfortunately be tinctured with some reference to the novel. It is a pity that so-called "dramatizations" can never be judged fairly. To one who has read The Constant Nymfh in book form, it is astounding to find in the play so much of the character detail intact. But to one who has never read the book and is seeing the play, are not the characters all artificial puppets, motivated by unbelievable cross-currents of emotion? Do not their psychologic processes seem vague, incoherent, frequently passing all understanding? Is not the hero, Lewis Dodd, for example, merely obnoxious? To all who are familiar with the book, the dramatization is comprehensive, for it depicts all on a vast canvas—all except Sanger, the half-cracked composer so curiously representative of what is termed, in jest, the old school. It is Sanger whose predilection for brandy and women led his fulsome life through devious paths. It is Sanger who falls like a shadow across the entire printed novel. His death is chronicled, I believe, as early as page 76, yet his Svengalese fascination lingers until Tessa, too, is dead— and the story comes to its close. In the play, Sanger is never seen, although his death-rattle breaks through the calm of the Karindehiitte, —the Sanger family resort in the Austrian Tyrol,—at the beginning of Act I. From then on old Sanger is quite forgotten, yet so infinite are his possibilities as a dramatic "influence", that a periodic attempt to inject him into the drama would surely not have been amiss. Bourdet managed the same device splendidly in The Caftive by contriving entirely to keep his real leading character off the stage, to the ultimate heightening of his dramatic effect. So much, however, for Sanger.

It is in the very first scene that The Constant Nymfh gets off to a bad start. It depicts, to be sure, some degree of the perpetual confusion of the Sanger household; it acquaints us with Tessa, Paulina, Antonia—Sanger's "clever" daughters—and it acquaints us so well with each of them that we yearn to know more of their fortunes. Tessa is the "leading character", yet so much time is devoted to her other sisters that a division of interest results. Only Tessa is carried to an ultimate conclusion, yet surely Antonia is interesting, for it is of her that Miss Kennedy writes, "to the experienced eye her promise was infinite" and adds that she was a lady "reckless rather than intrepid".

We follow Antonia through her prosaic marriage to Birnbaum, the art-lover who used to produce the musical melanges of Sanger, and we leave her, to be sure, in a state of impending maternity. But for all of that the thought persists that Antonia is fated to have a life as vivid as it is chequered.

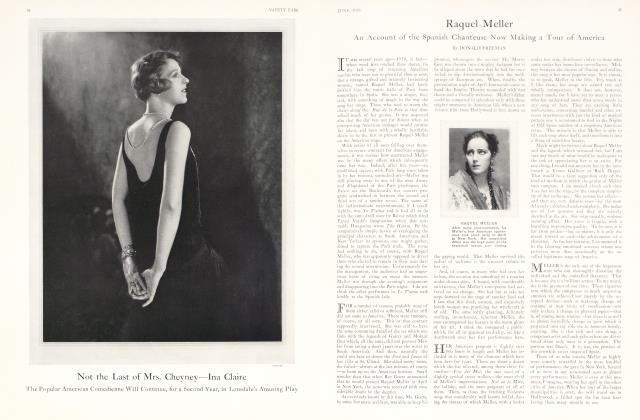

Even Paulina arouses our curiosity. The extraordinarily fine impersonation by the young and gifted Miss Helen Chandler may have been the decisive factor in making the character a provocative one, for Paulina seems destined for a career far more interesting than Tessa's whose life stopped short in a secondrate lodging house in Brussels. The inclusion of an excessive amount of dramatic material —a good part of which is discarded later on without having served any dramatic purpose— further slackens the play's crescendo. An interlude—the performance of a musical charade (with the music actually written, by the way, by Mr. Eugene Goosens, the conductor)—is also vouchsafed the audience to no purpose other than to give the play a musical "atmosphere".

The rest of The Constant Nymfh is far more commendable considered as drama, in the technical sense, but it is marred by a great unevenness. Only Tessa's death scene approaches real distinction and it is taken almost word for word from the book. The scene before this (in the Artists' room of the concert hall where Lewis' symphony is acclaimed, and from whence he flics with Tessa to Belgium) is playwrighting at its worst. This is such an episode as might have been written by Sacha Guitry' at the age of five. It is truly amazing how quickly a stage can be surfeited with an excess of sentiment when a pair of kindhearted concert hall janitors join the faithful family servant in wishing a young couple godspeed, as, wet of eye, the assemblage throw home-made confetti upon the heads of the (illicitly) eloping pair.

HERE M r. Basil Dean must be taken severely to task. I will first identify him as an English stage director of whom it has been said that he was selected for his trade "because of his fine manners". To his direction principally may be attributed the disjointed effect which the play gives to the onlookers. He has made no effort to give the play unity, and has, at times, resorted to the old-time directorial tricks which distinguished his production of London Life at the Drury Lane Theatre three seasons ago, an enterprise so little appreciated by the London public that it almost caused the venerable institution which housed it to close its doors forever. I refer particularly to the scene in the local production of The Constant Nymph which shows Lewis after he has married Florence and she—a chance visitor to the Tyrolean home of the Sangers with whom he became enamoured—has with some access of bitterness learned the fallacy of the doctrine which enticed her into matrimony with Lewis: "It must be splendid to live with a genius and help him in his work."

This scene, purporting to represent a soirée among the musical, resembled nothing so much as the tea party given by the Yorkshire yokelry in the perennial English success The Farmer's Wife. At times it descended to downright slap-stick, and only lacked a German comedian to put it in direct competition with the local burlesque entertainments. Again, when Florence has discovered the love of Lewis and Tessa, there ensues, thanks to Mr. Dean, a scene so demonstrative that in the course of it Tessa is thrown violently on her face by the enraged Florence, in a manner reminiscent of the corpulent Madame Segond Weber of the ComédieFrançaise in her famous role of Phèdre. Mr. Dean has, moreover, caused Florence to be entirely misrepresented. In the book the author has taken into account the flaws in the character of Florence and built up a delicate and adroit defence against them. But in the play Mr. Dean will have none of it, and the means whereby Florence lured the cagey Lewis Dodd into matrimony must ever remain a mystery.

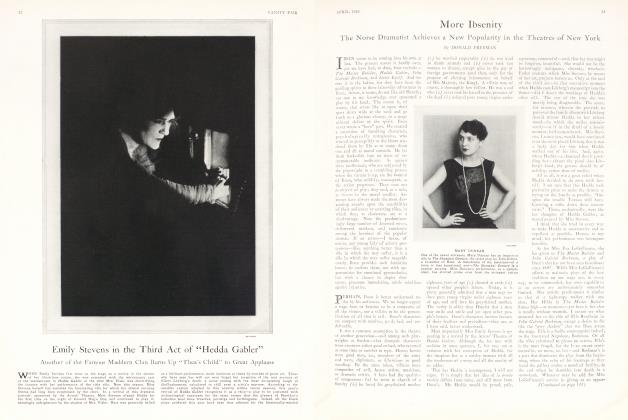

I do not know exactly how much Mr. Dean had to do with the casting of The Constant Nymph, but his choice of Glenn Anders as Lewis was a most unfortunate one. Mr. Anders' devotion to his art has caused him to dye his hair (in accordance with Miss Kennedy's description in the novel) a red so exquisite that the like of it has not been seen since Henner painted his famous nudes. Yet he fails to make Lewis Dodd a credible personage. That Mr. Anders' Lewis could have inspired grandes passions in the hearts of two such diverse women as Tessa and Florence is a feat too difficult for the imagination of even the most careless playgoer. As for Tessa, she is competent throughout—but does not bring to the role the fine feeling and the beauty with which it is permeated. The search for a Tessa, for the American production, has been a thorough one, and all manner of American actresses were mentioned in the course of it from Mrs. Fiske to Baby Peggy. Yet the choice eventually fell upon Miss Beatrix Thomson, a recruit from England almost as new to the stage there as here.

(Continued on page 102)

(Continued from page 45)

She was, as I have said, merely competent. I think the search for a Tessa might have ended with Helen Chandler. If this young actress—playing second fiddle to Tessa in the current production—would not have brought more glamour to the role than the mime who now occupies it, I am a very poor judge of dramatic talents. The Constant Nymph will not, I am sure, have the success which a more selective dramatization of the book would deserve on the New York stage. The play, as it stands, depends, not on its content, but on the interpretation of its content. In other words, it is a play which needs to be acted to perfection. And, I may add, the current production is without a single brilliant performance—with the exception, perhaps, of Miss Chandler's Paulina.

But, speaking of constant nymphs, I am in receipt of a communication from the Society for the Suppression of Vice asking for funds with which to put down evil plays, and propounding the awful question: "What are you doing to protect the children of your neighbours?" And appended is an after-thought: "How about the multitude of spectators (at The Captive) who were not adults? How about the young, curious, half-educated girls who thus gained information and had their curiosity aroused on a subject that would not otherwise come to the attention of 95 per cent of normal people during their natural lives? "

This suggests, in fact, that The Captive is not considered all that it should be. I wonder whether the Society for the Suppression of Vice realizes that The Constant Nymph, in its own way, teaches little girls that chastity does not pay. Tessa's death scene is very affecting—quite touching in fact—and it is welcome for its own sake. But why a death scene? It is not the consequence of events, nor even the "moral ending" which follows traditionally on the heels of sin. It may seem to the professional censors that death equalizes all infringements of the moral code, yet I am sure they will be disappointed to discover that Tessa's death is by no means a logical outcome of sinful intent. Early in the play it is "planted" that she is subject to heart attacks. Were it not for a most unusual physical infirmity it is reasonably sure to most of ns that Tessa's principles would have triumphed, vindicating completely her reckless love for Lewis. How will the censors explain this to the little girls they are so anxious to protect?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now