Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Foreign Debt and America

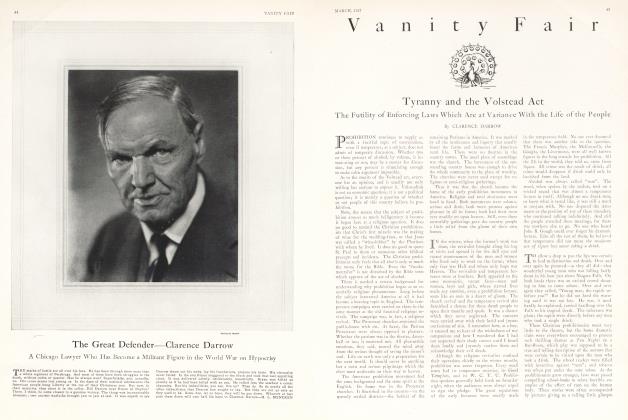

CLARENCE DARROW

Why Our International Attitude May Have Serious Consequences for Our Country

FOR a number of years the United States has been growing rich at an amazing rate. We are now very fat. In fact, we are obsessed of our lard. When we think of ourselves we think about our fat, and when we talk, we talk about our fat. The national urge is for more fat. In fact, nothing else counts, unless it is the desire to brag about it. We have most of the gold in the world. We are the financial centre of the earth. All the people of the world come to America to borrow money. We are glad to loan this cash at exorbitant rates and unconscionable commissions. We are fat all over, but especially we have fatty degeneration of the heart. This is a dangerous disease. As a nation we have made the same sacrifices that individuals make in growing obese rapidly. We have lost all our friends. We know that when any nation speaks a good word for us, it is a sign that they want to borrow money. This is a ticklish position for a nation, exactly as it is for an individual. Still, why should we care? We can lick the world! We have more iron and coal and other raw material than all of Europe put together. We have more machinery than the others. We have more brains applied to production than all the rest. In fact, all our brains are applied to production. To what other use could real brains be applied? No one stops to inquire why we should want to lick the world—or what good it would do us to thrash it. Neither do they inquire why we want to be so "fat".

OF COURSE our fatness is not very evenly distributed. Many of our people are lean; but lumping us all together, and designating the lump as "we", the world has never before witnessed such obesity. This condition has come about very quickly. Strange to say, we were accumulating our fat while the rest of the world was growing poor. Our great financial corpulency grew out of the late war. The impoverishment of Europe likewise grew out of the late war. We were a comparatively new country before the war. England was the financial centre of the world. England was the financial centre because she was older and nearer the centre of the world's population. England still is older and nearer the centre of population, but she is now very poor, while we are very rich. If abundant fat is a good thing, then the war was a god-send for America. Every European state is now close to bankruptcy. The immediate future of all Europe is a serious question. Her people are over-taxed and idle and in want,—meanwhile we are rich. Is their poverty any concern of ours? Our politicians seem to think that it is not. They think it is not, because they believe that their constituents feel that way.

The United States was involved in the European war long before we openly took sides; we sold everything that we could spare to the warring countries. We sold at exorbitant prices. We were able to get these prices because our customers were in dire need.

AFTER two years of carnage in Europe we went into the war. We had no right to take sides for any reason other than that our national interests were involved. From the beginning many of our people considered that our rights were invaded. It is not necessary to discuss whether we did right or wrong in going in. At least we thought that the rights of America were involved and we went in on the side of the Allies. We had no army and only a small navy. We had no munitions of war. We had one thing needful to war—Cash. We also had the food and material that our allies needed for carrying on the war. Our soldiers reached the front only in the closing days of the contest. Our money and food reached it long before. As soon as we entered the war we began to furnish cash and supplies to our allies. The armies of Europe were in the field and had been for two long years. True, their ranks were depleted by shot and shell, and disease and famine. Still, in spite of that they were holding the line. By the time we entered they were hanging on in grim despair, willing that every man should die, if need be, in the cause. Not only the most fitting of the Allies' soldiers had gone down to death, but a large part of their property had been destroyed. Hundreds of cities and villages had been riddled with cannon balls and desolated with flame. All the Allies had contracted debts without limit wherever they could sell their bonds, and at whatever price. The United States had stayed out of the war, but we had sold supplies at exorbitant rates, for cash, from the first.

When we finally went in, we gave our allies cash to buy supplies, mostly in America, —some ten billions of dollars altogether. We furnished them no money until we went in. Up to that time we had taken their money for the stuff that we had to sell. Our soldiers were ready for war only in the closing days. The United States lost some 50,000 dead, while the Allies lost ten millions, at least. How many millions of American lives were saved by the cash we gave our allies?

The war was won by the help of American money and by the lives of the Allies. Our money was furnished after the Allies had poured in all that they could give or borrow from every other source. The war was won. Our dead numbered 50,000; theirs, at least 10,000,000. The money we gave was about $10,000,000,000. They gave all that they had, which was vastly more. We arc now rich. Too rich, in fact. So rich that we arc in danger of death from fatty degeneration of the heart. When I say in danger of death, 1 mean the death of all that once was the finest and the bravest and the truest in American character.

After we got in, and growing out of the general effort to win the war, America received war bonds of the allied countries for this ten billion dollars. We arc told that the Allies should pay; that they "hired the money". Did they "hire the money", and should they pay the bonds?

THE Congress and Senate who voted this money to help the common cause did not expect it to be returned. The leaders in both houses made this plain when the money was appropriated. The people did not expect it to be repaid, nor did they want it to be. They were thankful that the Allies could shorten the war by sending their remaining men to death, while we furnished the supplies. Who had the best of this bargain, our allies or ourselves? Every American soldier who returned from the shambles of Europe knows what it meant that the war was prosecuted with our money before our soldiers reached the front. Every American father and mother whose sons returned alive knows how little was our contribution compared with the lives sacrificed by Britain, France, Italy and the rest, during the long months while their sons were dying and America was furnishing the supplies.

It is true that many of our people did not believe in the war; the justice or injustice of our entrance is no longer a matter worth discussing. For myself, I believed we should go in. At any rate, we did go in. And pledged ourselves to fight it to the end. And, of course, whether men believed in it or not, they were compelled to go. It is not now a question of whether we were right or wrong, but whether a nation as corpulent as ours should take money from nations that were our allies in this common world disaster; and nations that did infinitely more to bring victory than we ever dreamed of doing.

THE bonds of our allies lack every element that is necessary to make a valid obligation. America gave the money to save herself, and for two years before that time the Allies were fighting without our help. We never expected it back, nor even wanted it to be returned. The Allies who gave their bonds could do nothing else. They were in a death grapple and of course were heartened and jubilant when at last we went in. They could do nothing else but pledge their people with their bonds; neither America nor the Allies expected it to be anything but a small contribution on our part to a common cause.

These bonds arc not such obligations as call for the strict rules of legal construction. They are rather instruments that should be determined in the light of Equity. They have not been transferred before due to innocent holder for value. They arc still in the hands of the United States. Besides this, it is a question only of what the people of the United States think should be done.

Every principle of Equity is against us. Rather should we contribute still larger sums to our allies. If we were ever justified in entering this war, it was in Equity our war from the beginning. The need for the defeat of Germany was just the same when the war opened as it was when we went in. For two terrible years our allies fought this war without our aid. More than that, every American was greedily gathering every dollar of profit possible to be garnered on account of the holocaust in Europe. We sold our stuff at the most exorbitant prices and demanded cash or good security for our wares. America as a nation would doubtless be vastly ahead in a financial way, even though we never collected a single penny on our European bonds. Does this mean nothing to a people who arc at heart really big and generous and fair?

LET us think, too, of who must pay these A bonds. First, England, who practically endorsed all the war obligations of the Allies. England, who risked her empire and the fortunes of every Briton in the contest. I am aware that many Americans do not like the English. I am not of that number. I know too much of the history of civilization not to recognize the debt of the world to England. Great Britain is now staggering under an appalling load of debt. Her industries are languishing. Her people arc suffering. She is willing to cancel her debts against France and Italy and the other Allies whose obligations she underwrote. After Great Britain, France is the next who must pay. France was the first nation to suffer from the German attack. Many of her cities were ruined and her country laid waste. A generation of men were killed and hopelessly maimed in the carnage. Her country is small and her population large. Her people are excessively poor and over-burdened with taxes. Where is the American who wants her money? It is not even needful to call attention to the fact that but for France our American Revolution would have been only a rebellion. Italy, too, made great sacrifices in the war. She is very poor. Her national resources arc small and her people over-burdened. What is true of these countries is even truer of the still smaller countries from whom we are demanding money that was used to help us as well as them, and money, moreover, that we do not need.

NOTHING further than this demand upon our allies is needed to stamp us in the eyes of the world as Shylocks, devoid of sentiment and a sense of justice. If anything more is needed, it is shown by our attitude toward the world in reference to trade. How are our former allies to pay what we demand? They have no gold; all of this is in America. They can give new bonds for old, but this only postpones the payment and adds to the obligation. There is but one way, and that is by the products of the European people. For two or three generations, at least, the poor of Europe must work to pay us money that we do not need and should not take. Have we no feeling for the unborn children who must bear this load incurred in a common cause? But even this will not satisfy America. We will not buy from Europe. Our tariff-wall is so high that we keep out foreign goods so that our "market-mongers" can fix the prices of their wares. We want the money which we should not have, and will give them no chance to pay. I know of only one parallel for our attitude, and that was the demand of the Egyptians on the Hebrews to make bricks without straw. The Hebrews did not comply.

THE world (outside of America) is in dire want, growing out of the World War. Its civilization is in danger. Anything may happen in any European country. Does not human feeling and fellowship call on the richest country on earth to help? No man can live to himself alone, and still less can any nation live to itself alone. We have made all the people of the world our enemies. We are strong, but not so strong that we want the world against us. As a man needs the friendship of his neighbours, so nations need the good will of other nations. The least we can do to get that is to cancel the bonds incurred for our help in the late war. This 'simple act of justice would bring hope and courage to our allies. For one, I should be glad if it were done on condition that the Allies should forgive the indemnities from the Central Powers, but we at least shou'd cancel our allies' bonds; and eventually it will be done. It should be done now. America should do something to raise the gloom and despair that overhangs Europe. She should do something to make friends with the world. She should do something to redeem herself from her reputation of a Shy lock and a usurer. This is the least she can do, and it really will cost us nothing. The cancellation of foreign indebtedness growing out of the war will bring us collectively, and individually, more return for a smaller outlay than anything else can bring. Surely that should commend it to our people even if nothing else docs.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now