Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowLiberty, Equality, Fraternity

Why Rights for Women Have Brought About the Decline of Some Notable Institutions

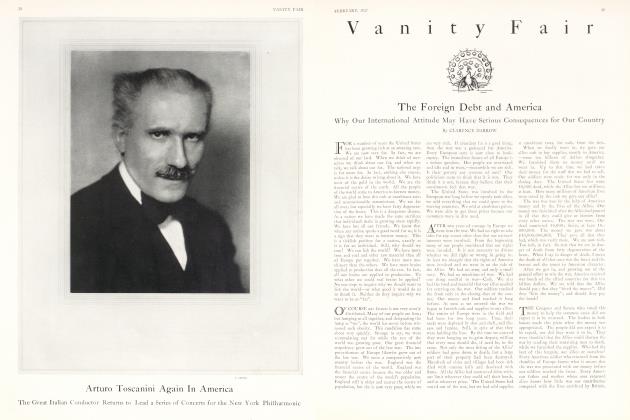

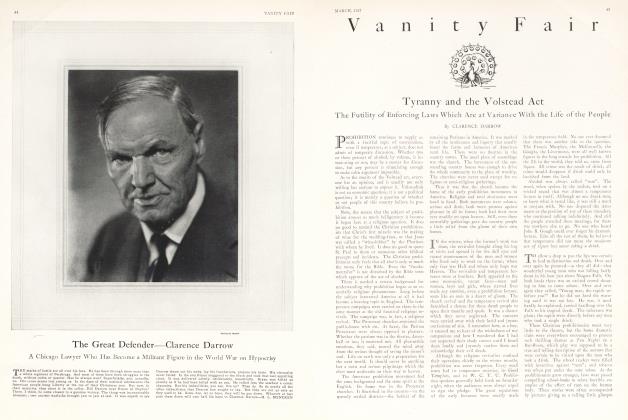

CLARENCE DARROW

I AM not one who objects to change, but there arc some innovations that I resent. For instance, prohibition annoys me; not because 1 ever cared much for alcohol, but because prohibition has taken so much good feeling and colour out of life. Then there are the barber shops. I have always liked barber shops; true, in common with many others, I got the safety-razor habit years ago, and this kept me out of barber shops except on those rare occasions when I visited them to get my hair cut. I liked the red, white and blue stripes winding down the barber pole. Somehow they seemed to be a symbol of liberty, even after the reformers began to discredit and curtail freedom, and women began to be emancipated.

The barber and his shop have a history. And because the degeneration of the barber shop proves an important point, I shall tell what 1 know of their history. In the olden days the barber was the surgeon, and some of them to this day continue to let blood. The barber shop was not only the place to get a shave and haircut but it was likewise the social centre. In fact, historians tell us that in the Eighteenth Century in England the barber shop was the favourite resort for "idle persons", and in addition to its attraction as a focus for news, a lute, a viol, or some such musical instrument, was always kept for the entertainment of waiting customers.

The musical instruments had disappeared before I began to frequent the places, but the "idle fellows" were still there. These always seemed to have leisure and were found sprawling comfortably over the big chairs—never too busy to wait for a shave. They were good conversationalists and spoke without restraint, discussing in an easy and colourful way the topics of the times. They were well posted on race horses, chorus girls, prize fighters, elections and other interesting and manly topics. Their language was not always grammatical nor their stories chaste. The barber shop frequenter had a rich "lingo" of his own that seemed to fit the place. It vied with the Pullman smoker as a centre for the distribution of droll stories.

I WAS raised in a small town in the middle West where democracy was real and social intercourse was easy. On Saturday nights when the "hired men" came in from the country they gravitated to the barber shop. In those days conversation was still an art; the barber shop promoted and cultivated this art in its own way. Altogether it was an important social centre and was, in effect, a community club where neither initiation fees nor dues were demanded, and, best of all, it was for men only. Its precincts were never invaded by women, and so its votaries knew but few inhibitions.

Of course, in the early days the barber shop was not the only man's club. The automobile had not then driven out the horse, and the livery stable was a common vendez-vous for men on Saturday afternoon. Here, too, would foregather the good fellows of the town and country round. It was especially the headquarters for local statesmen. Amid flies and pungent odours political fortunes were made and lost, and the Constitution was defended against its foes.

And then there was the saloon of grateful memory. This, too, was an institution where men could gather by themselves. Under the influence of stimulants they grew sociable and even loquacious. Leaning over the bar with one foot resting on the brass rail, they discussed politics and religion, horses, and men and women, and argued and conversed and loved each other to their hearts' content.

On rare occasions the polls had much the same atmosphere. But after the advent of "Woman's Suffrage", with "lady" clerks and "lady" judges, the lounger disappeared from the precincts on election day and conversation grew restrained. The men stopped telling stories, they took off their hats to vote, and left their cigars and pipes outside the door. Voting became almost as solemn and silent as a religious rite. Men no longer went to the polls for social intercourse, to toll stories, to discuss their neighbours, the women and the candidates. The place was clean and shinv and uncomfortable and no man cared to linger. They came in solemnly, deposited their votes and went back to work.

Alas—the livery stable, the saloon and the polls lost their pristine charm. Men were driven from pillar to post and the barber shops alone remained as the last fortress for their vanishing fellowship and freedom. Women still wore long hair and long skirts, and there was no excuse for them to intrude themselves into this last sanctuary. For a time men made the best of what was left. The barber himself was an institution. He had long since forgotten that his ancestor was a surgeon and he never "put on airs". He was a master of conversation. He was always loquacious; he could discuss religion and politics and all the other questions of the day. His observations were not only enlightening and interesting but were likewise discreet. He always had views about debatable subjects but he never intruded them. While he slowly stropped his razor, made his lather, and soaped your face, he skillfully drew you out on these important subjects. He never expressed his opinion until he heard from you and he then,

invariably, agreed with what you said. The barber never gave the impression that he was greedy for your money. He did everything with the leisure which marked the true gentleman. While you reclined restfully in his beautiful plush chair he generously lathered your face, then carefully washed it off, and covered it with hot and cold towels in turn. After the second or third shaving there were no end of lotions for your skin. He wound up his gentle ministrations by combing your hair in the most meticulous way, and let you go out happy and looking better than you had since the last visit, or would again until you came back for another shave.

DURING this performance he regaled you with stories of race horses, giving you fresh and private tips from "God knows where". Often, too, he led up discreetly to the information that he could place a bet on the races if you wished him to. No objectionable people ever came to the place. One never met a clergyman or a deacon there, or any person whom you had to "look out for", or who took away your comfort or your ease. For a brief hour the place was yours and you felt perfectly at home. Somehow the barber shop was the only place you visited where you never seemed in a hurry to get away. If you were not "next" it did not matter. There was literature and colourful pictures on the wall. These pictures generally portrayed chorus girls, horses, dogs and sporting men, wearing red coats and riding on horse-back following the hounds. In the way of literature there was always the Police Gazette with its pictures of lovely actresses wearing tights, a novelty in those simple days. There were pictures, too, of thoroughbred dogs and race horses, together with stories telling their ages and pedigrees and their marvellous exploits. If literature and art failed to interest you, there were sociable and congenial fellows lounging in the chairs, and the formality of an introduction was never needed to make you friends. The barber shop made all men kin. In the middle of the floor was a battered brass cuspidor, shinv in spots, or a square box filled with sand or sawdust. In front of the barber chairs was a large mirror covered with fly-netting in the summer time. You could loll back and see the barber "come at" you with his sharp knife. You could watch your changing face and head slowly emerging under his magic touch until it became a thing of beauty, and almost made you a stranger to yourself. By had of course, realized that in many ways the world was changing; that new machinery and a modified social life were making their inroads everywhere. With all the rest I knew that the Nineteenth Amendment, bobbed hair and women's clubs were "ladyizing" the world. I had never realized that the barber shops, too, were suffering from the blighting touch of new ideas and social customs. I had never seen a

Continued on page 110

Continued from page 74

Alas, it was not the at I knew and loved. modulated to a lower talking. He was a respectful man. He look like a barber. ressed like the secretary of the Y. M. C. A.—at least he always fancied that ought to look. He told have to wait a few should I kindly take a t even tell me that I ked around and lo— barber chairs was a and seated in another - turn, was a middle ing woman patiently an Science Monitor.

fled in dismay but I As I was obliged to for a Police Gazette— amazement there was On the table was a Companion. My eyes niliar pictures on the were the dogs and red coated men. In ime decoration was a and, to my amazement were I once would have coloured lithograph, I Mother. When I went WAS SMOKING a cigarette. took it from my mouth flip it towards the cussand in its wonted place. In fact, the was no cuspidor anywhere in the shop The floor was covered with a neat mag It was spotless and antiseptic, be wildered, I threw my cigarette out of the door and sat down to wait. I did not even try to read. I had no objection to the Woman's Home Companion —but I felt that its place was in the home and not in the barber shop I looked for the old time rack of cups bearing the names of the Who's Wlio citizens, but it, too, had disappeared like a far-off dream. In its place was a cupboard, and as the barber opened the door I saw, to my dismay, powder, lip-sticks, rouge and what not. The cupboard was barren of everything that belonged to a barber shop. Penf sively I waited for my turn. This young lady was giving directions to the barber: "Cut the ends just a little bit at a time so we can tell when we strike the outline that I want. Don't go down too deep at the back of my head, where it's flat, you know."

"Yes, yes—I remember," answered the obliging young man; "you'd loot good with a swell new wind-blown touzle."

In the mean time the lady who was observed reading the Christian Science Monitor had taken another barber chair which had been vacated by the occupant. She held fast her Monitor

over her ears, chummily asking, "Would you have a hot oil shampoo, if you were me, or would you wait until I have my next marcel?" The barber hesitated, thoughtfully, before replymg, "Well—for your style of coiffure I'd advise only water-waves. We have just got in a Ritzie line of water-wave comb-sets, in that big show case next to those 'Vanity Razors.'" "Oh, razors remind me," confidingly whispered the pretty patron, "this is the day—"

The door opened abruptly and a man and woman entered the shop. I realized that again and again I must give my turn to "Ladies First"—that no matter how long I waited I might never be "next"; that woman has taken all the so-called advantages that man once had and yet clings fast to her old time privileges as well. I realized that for some years past man has been slowly losing his place as "next". In fact I doubt if he had. ever been really "next". This idea was probably only apparent,—a delusion like most of life,

I waited no longer, but fled from the shop. As I went away I pondered over the long steady invasion of women into what was once man's domain and what this invasion means to both. Is not the so-called "Woman's Awakening" taking the colour and freedom from the world? Is it not slowly and surely destroying the illusion and the romance which lure the born and the unborn alike in the prime venture of living?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now