Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Secret of the Zoo Exposed

Proving That Our Fear of Wild Animals is Done with the Aid of (Freudian) Mirrors

E. E. CUMMINGS

O DOUBT most people accept the "scientific" theory that man is an ex-monkey which somehow or other developed at the expense of other animals. And no doubt these readers have visited a zoo, there to experience thrills which no theory, scientific or otherwise, could satisfactorily explain. But have they ever thought of the possibility that what we are accustomed to call "animals" arc in reality living mirrors, reflecting otherwise unsuspected aspects of our own human character? Such an idea sounds absurd; but so do many ideas which arc found to contain a surprising amount of truth. The zoo, with its mysteriously impressive and often positively unreal inhabitants, may be something entirely different from what we imagine. We may even discover, while investigating the zoo, something of great significance for the understanding of ourselves.

An astonishing fact confronts us at the very outset: nobody seems to know what the word "zoo" implies. This word, generally speaking, suggests little more than a highly odoriferous collection of interesting and unhappy animals. Whoever takes the trouble to look it up in a dictionary will find that "zoo" comes from the Greek zoon, meaning "animal". The misapprehension that zoos have to do with animals would appear to be universal. Actually, however, the syllabic "zoo" originates in that most beautiful of all verbs, zao, "I am alive"—hence a zoo, by its derivation, is not a collection of animals but a number of ways of being alive. As Hamlet might have put it: "to zoo or not to zoo, that is the question."

WE NEXT observe that each and every zoo constitutes both a playground and a prison. For each and every zoo is founded on certain acres which have been captured by civilization, from civilization, on behalf of civilization and which acres are themselves the homes, and captors, of certain essentially non-civilized entities, commonly referred to as "animals". From one point of view, the typical zoo means a virtual chaos, whereby human beings arc enabled temporarily to forget the routine of city life; while, from another point of view, it means a real cosmos, possessed of its own consciousness, its own quarrels and even its own social register—which, as we shall soon sec, is indirectly our own social register. These two aspects, "human" and "animal", interact; with the result that the zoo, in comprising a mechanism for the exhibition of beasts, birds and reptiles, becomes a compound instrument for the investigation of mysterious humanity.

But what, precisely, do we mean by "interact"? We mean that the zoo's permanent inhabitants, the so called animals, arc kinds of "alivencss" which we ourselves, the temporary inhabitants of the zoo, experience. To speak of "seeing the animals" is to treat this phenomenon with a shameful flippancy, with a clumsiness perfectly disgusting. Actually, such "creatures" as we "sec" create in us a variety of emotions, ranging all the way from terror and pity to happiness and despair. Why? Not because the giraffe is effete, or because the elephant is enormous, but because we ourselves appear ridiculous and terrible in these amazing mirrors.

Now let us try to understand the zoo as a concatenation of differently functioning and variously labelled mirrors, all of which arc alive. These living mirrors, mistakenly called "animals", arc for the most part grouped in systems or "houses", like the "bird house" and the "monkey house", and each house or system furnishes us with some particular verdict upon ourselves. In passing from house to house, from one system of mirrors to another system of mirrors, we discover totally unsuspected aspects of our own existence. At every turn we are amused, perplexed, horrified or dumbfounded. No mere spectacle of monsters, however extraordinary, could so move us. The truth is, not that we see monsters, but that we are monsters! What moves us is the revelation—couched in terms of things visible or outside us—of our true or invisible selves. This alone explains why our hearts pause with dread, why our eyes bulge with astonishment and why, when face to face with a peculiarly fabulous image, we have all we can do to keep from exclaiming, "Impossible! Such a phantom cannot really be alive: I must be dreaming!"— which conviction is well founded, for in a sense we arc dreaming.

Hereupon, the gentle reader will doubtless cry: "Enough! I have tolerated that absurd quibble as to the meaning of 'zoo' , I have endured that far-fetched comparison between animals and mirrors, but I positively will not permit you to accuse me of dreaming when, with open eyes, I see real lions and tigers which would be only too glad to cat me alive if it weren't for the iron bars between us."

Perhaps. Nevertheless we must insist that going to the zoo is very like dreaming. Let us remember that the essence of dreams fer se is, not that they seem unreal to us after we have awakened from them, but that they arc profoundly and completely real to the dreamer. The lions and tigers of the dreams which you and I arc dreaming possess quite as much reality as any tigers and lions (social or otherwise) which our open eyes have ever seen. Frequently, indeed, these dream monsters are even more real than their "real" counterparts. But between them and us there is something which saves our precious lives; just as, in the case of the zoo, there are iron bars between the panther which springs and the spectator who stares. Nor should we forget that the frightful monsters of dreams, if properly analyzed, lose their terror and become deceptive appearances, harmless symbols of our own hates and loves. For further enlightenment on this subject I can only refer you to the works of Dr. Freud and the other psycho-analysts. But why is it that our hates and loves are able to express themselves in these forms during sleep? Obviouslv, the phenomenon has previously occurred in consciousness and the leopard which seems so "real" to us at the zoo is only an embodiment of our own stealth and cruelty—a living mirror of our own power and cunning.

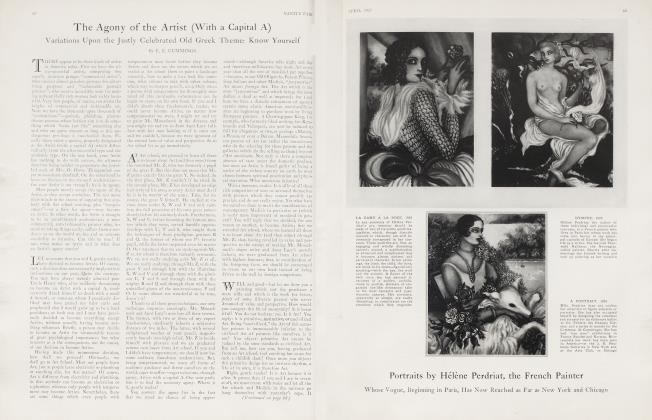

SOUCH assertions as the foregoing cannot, of course, be mathematically proved. But suppose those individuals, who doubt our wisdom and who arc too busy to visit the nearest zoo, consult the pictures accompanying this article. We realize that the test is not a fair one. No matter how excellent Mr. Underwood's pictures may be, they are only pictures after all, and not living "animals". When one looks at a cat or at a leopard or at a porcupine or at a snake or at monkeys directly, one sees (according to our theory) an image of oneself—an image necessarily different from that image of himself which the creator of these pictures has seen and recorded. However, the principle involved is the same. A magic mirror is still a magic mirror. Let our skeptical readers, then, gaze upon these magically entitled, magically functioning mirrors which we have provided for their personal use and find out what sort of ladies and gentlemen they—our readers— really arc. We have a very small favour to ask: that, having looked and seen themselves, they will not pounce upon, strangle and tear us limb from limb, nor yet shoot any barbed quills in our direction!

One mightily significant mirror, labelled "Oracle, or, A Living Portrait of Civilization", is absent from the above-mentioned collection of mirrors. This oracle of Civilization, albeit a resident of the "birdhouse", cannot be found among the Green Manucodcs nor yet among the Twelve Wired Birds of Paradise. Astonishingly enough, gentle reader, it is only Poll Parrot—who perpetually unites the myriad meanings of existence in the supremely synthetic exclamation—"Hellogoodbye!'"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now