Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA Philosophy For The Films

How a Triumphant Ego Links the Intellectuals and the Motion Pictures in a Common Bond

GILBERT W. GABRIEL

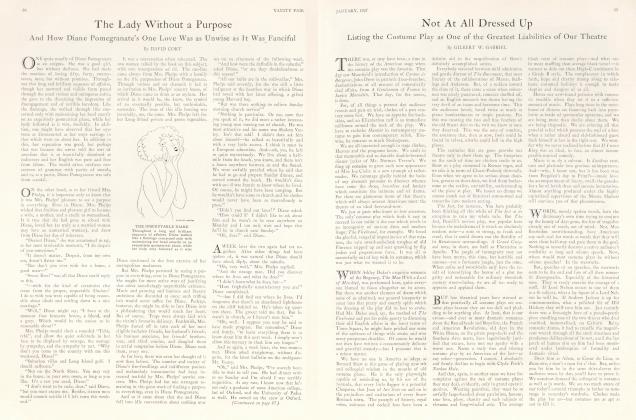

AT opposite poles of the earth—so both of them will tell you—are the motion pictures and the intellectual. Nothing is more humiliating to the young playwright in Mr. Tarkington's new novel, The Plutocrat, than that he should he saved from starvation by a motion picture contract. Yet, in different tongues, both motion pictures and the intellectuals speak the same thought.

The revelation came to me in the course of the familiar and banal convolutions of a typical film. The impact was staggering, yet in the watches of the night the realization came also that, the credos of the films and the intellectuals being what they are, the coincidence of the two is logical and inevitable. The hero of the picture had deserted the heroine, his wife, because her pay-check as a cabaret dancer exceeded his, as a tie salesman, though lie loved her dearly. In the closing passages of the film, when he had handily made a fortune that enabled him to return to his wife without loss of self-respect, the dens ex machina of the plot addressed the hero somewhat in this wise: "Never again, my boy, let pride come between you and your true love."

In that instant I knew. Pride—or, more properly, in this instance, self-respect—though a virtue today in some disrepute—is an admirable, albeit frequently inconvenient, trait. It is the keystone of what is called "character". Hut Hollywood dictates that, for pragmatic reasons, pride must he put aside if it stands in the way of gaining one's objective—in this instance, the consummation of love. Thus the motion pictures catalog themselves as pragmatists and hedonists. Are not these titles better known as the plumes that the pure intellectuals, the cream of the cream of the intellectuals, have for long borne with engaging arrogance. The intellectuals, too, hold pride in low estate. They, too, consider character excess baggage for the true artist. The Oscar Wildes, the Rodins, the Baudelaires, the Walt Whitmans—all the Peck's Rad Boys of art— were above the conventions and prejudices of common men. Thus, as frequently happens, extremes may be made to co-incide.

THE same trampling down of backgrounds, the same war against the community, the same extolling of the individual, the same fierce, untamed resolve to clear the road between man and his own true love is noticeable in the manifestoes of both the intellectuals and the motion pictures. The intellectual exploits this doctrine in words of six syllables, and pours quotations from Ellis and sixty psycho-analysts into the argument. But, at trumpeting the ego, the motion pictures take the low road and are there before him.

It is hard to name a single motion picture with a defeatist program, a single one wherein circumstances overcome the hero's pluck, the heroine's devotion. That German classic, perhaps, The Last Laugh . . . but even to the legitimate sorrows of the end of this picture it was found necessary to append a burlesque epilogue wherein luck turned and individual virtue triumphed. Nothing matters in the movies except the final success of the hero. Nothing is so much relished as his ruthlessness about attaining it.

The movies, left to themselves, would make anarchists of us all. They could not have a more healthful mission. They are aware that, just outside the motion picture palace's doors, life is mumbling itself away in the mournful numbers of street-corners; that ten thousand obligatory habits of society are demanding ten thousand renunciations an hour of those who tread the sidewalk out there. All hope abandon, ye who exit here.

Wherefore, in the scented, gold-encrusted hush within the house—within this "cathedral of the motion picture"—a high mass goes on: but a mass of no humilities, renunciations or peccavis. If not precisely a Black Mass, then at least Sepia, in the cool, sly, unembarrassed crepuscle wherein a music-hypnotized audience may have release from genteel poverty and common decencies and see itself enlarged to gods on mountain-tops and emperors laughing down at Rome aflame.

Pantheistic the moving pictures certainly are. The sheeted splendours of sunset on some glacial lake, the awe of a volcano hurling up hot fragments from the red core of earth, the white sweep of seas and the exultant hymn of trees in a clean dawn . . . these are all in and of the cinema's service. But man moves through them as an invariable conqueror, as a pivot around whose romance, wind and weather twirl with glad obedience.

That sunset, for instance, is the background whereon lovers are expressively silhouetted. That sweep of seas is sailing Jack home to his Susan, and those leaves that shiver to the dawn are like the fingers of a corps of violinists as they announce the love motif. Chateaubriand himself did not use nature so fondly as a lackey to the plot as do the meanest motion pictures.

Here, seen through the camera's monocle, is a universe of humans,—better, super-humans who have the knack to move mountains, to construct dams, to blow them up, to swim torrents on horseback, to plunge from aeroplanes upon the roofs of passing trains, to tame wildernesses and defeat all schemes of men and financiers. And all for what? For love's sweet sake? Yes, but love is only a side remark, concretely put, to prove the movies' theorem that each man owns the earth and is entitled to the rights and privileges thereof.

SCIENTISTS, pseudo-scientists and high-minded sermonizers will all assure you that, when love flies in at the ego, nobody should let pride interfere thereafter, or care for self-respect, for public morals or private commonsense or any other inhibitory reason. The will-to-love yaps hungrily—and must be fed. Whatever keeps it from its feast is harmful. Whatever stands between man and his own personal millennium is so much thorn and thistle, stuff for the scythe.

The motion pictures say "Aye" to that. They go the intellectuals one further. They hold it as a basic concept that love shall inevitably conquer all, and that self, which is love's major, shall never fail to break its fetters. The movies are not bothered by doubts, as their cousins, the intellectuals, are. They see life as through a lens, radiantly—and all is victory in their sight.

Catch a motion picture being troubled, for instance, about the mortal wounds of the villain who has tried to come between a pair of sterling, shining lovers. Your intellectual will have given the pair his scientific blessing, perhaps, and followed them to the altar with fine phrases on self-expression, the libido at large, and the future of the race. But, en route, he will have had to linger embarrassedly over the corpse of that third person, that extraneous one, the villain, and have had to grope through his mind's catalogue for reasons to justify the killing. It isn't so easy for the coldest of us to justify killings, either. Dostoiëvsky, for example, spent whole novels failing at it.

But the motion picture is in no such bondage. It does away with the villains in no time at all—and without a moment's misgiving. It freezes them nicely to death in the North Canadian snows, it sends them tumbling off into infinity and out of sight, out of mind, from a Colorado clifftop. It rushes in where the intellectual fears to do more than assert, and wastes not an inch of film thereafter on compunctions.

(Continued on page 104)

(Continued from page 58)

Not only flesh-and-blood villains are treated to this successful summariness. But those more subtle and more mortifying fiends which oppress the breast of each of us when we would be up and loving . . . the moving pictures swat each one of them away and never fear ghosts' return. If, for example, your pride of bloom has temporarily vanquished your intellect on the subject of miscegenation, go to the movies and they will be your allies and your champions. For never does a nice blond Nordic wed a Hawaiian hulahula maiden without every assurance that happiness is their eternal lot, rapture their key forever after, and the Mendelian Law just a wall-motto for their vine-covered cottage in a suburb of Hollywood.

Not that either the intellectuals or the movies hold a brief for sin as sin. They are simply magnificently a-moral, both of them, in that sense. They both agree that monogamy is a matter of patience, and marriage a matter of what you marry into or out of.

The czars and censors of the movies' morals will tell you an altogether other story. They will assure you that the plots they pass are certified Grade-A Pure, that the virtues are always rewarded by marriages made in heaven, the wages of sin are always death. Which, when you look on the movies as only screen-deep, is fairly true.

But, behind the screens, a world of glorious extremities and paradoxes seethes. A world wherein the woolly "chaps" of cowboys amount to seven-league hoots, en route for the Golden Age of love's fulfilment. A world literal in its costumes and almost monotone in its colors, yet too fanciful even to classify as symbolism. A world of Pompeian baths in London homes, of satin boudoirs in Grub Alley,of deserts fragrant with passion flowers. A world of oddities and anachronisms too lucky to be intentional, too spiritual to be born of anything but the primal and unruly spirit of a universe of shadows.

The haughty mind of the intellectual has been harping for the last decade on the supreme importance of doing and getting precisely what you want to do and get in and out of life. The moving pictures have given everybody, en masse, what they want—or, at least, taught them to go after it—all at the same time. But the intellectual would not be an intellectual if he failed to snub bis helpmate. For the intellectual has believed in all this as a theoretic principle, and has gotten no further with it than anyone ever can get with a principle. The movie has accepted it as a need, and has turned the need, if not into a virtue, at any rate into an axiom and a trade-talk.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now