Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowFor There Was No Room in the Inn

On Account of a Latter day Occasion When the Shepherds Watched Their Flocks by Night

COREY FORD

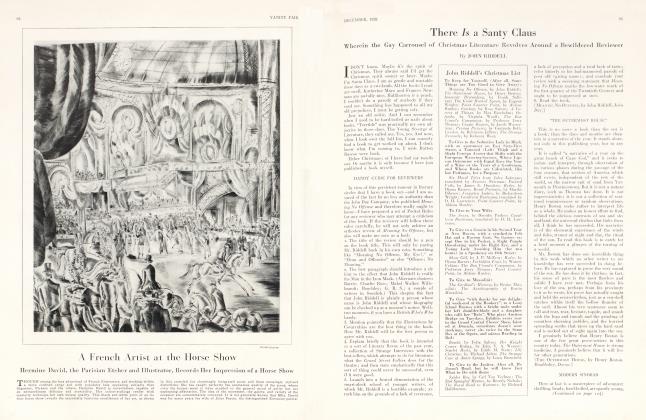

OVER the door into the main dining-room there was a large red bell of accordionpleated paper, which was suspended by two ropes of twisted greens. A sprig of mistletoe had been fastened to the clapper of the bell. The lights of the room were shaded with tissue-paper poinsettias and gave a red glow, and the dancing couples as they shuffled past the door sent long red-rimmed shadows reaching across the white tiles of the hotel lobby.

The room-clerk was leaning his elbows on the hotel-register, chatting in an undertone with a middle-aged man across the counter. The black covers of the register were stamped in gilt with advertisements of local dry-goods and grocery stores. Above the desk was a large sign "Welcome", decorated with artificial holly and poinsettia and a smaller red bell. Below this hung another sign "The Bethlehem Rotary Club Meets Here Every Tuesday at I P.M." and an insurance calendar showing a coloured picture of two gladiators fighting in an arena. The middle-aged man pushed his derby back on his head.

"Quite a layout."

"Yeh, we always have a big crowd around this time of year," said the clerk. "We like to fix things up a little homey."

"I try to get here every year," said the middle-aged man. "I always manage to come through here about this time. I like it."

"Why don't you go in and dance?"

"Naw, not me. I just like to look on. I'm too old."

"You can't always tell," murmured the clerk, without raising his eyes.

IN the doorway a white-haired man in a Roman toga, which was draped loosely around his skinny legs, grabbed a girl in a black mask and pulled her toward him heavily. He clutched the hard white curve of her back with his flat hand, and as she bent in a circle away from him the folds of her long Syrian gown gradually drew taut against her breasts. They were both laughing. He pointed insistently at the mistletoe above them with his free hand, and then she broke from his grasp and ran across the lobby and up the stairs. He followed her, holding up his toga like a skirt. The clerk repeated: "You can't always tell." The brass-throated orchestra was pounding out a current dance-number in the other room; the shish shish of plodding feet following the rhythm was as soundless as a steady rain. The street door suddenly opened and closed behind a bell-boy with a battered suitcase. It opened again, and a young man and a girl entered.

"Sit down over here," said the man, helping the girl into a straight leather chair. He adjusted her heavy shawl around her, so that only her dark eyes showed. He looked down at her gently a moment, and then he walked over to the clerk.

"Hello," he nodded, "I'd like a double room for tonight."

The clerk lifted his eyebrows and pursed his lips and turned his head to the left and to the right three times slowly. He smiled. "Do you mean you haven't got anything?" The clerk spread his hands and smiled more broadly. "Not a room in the place. Sorry."

"But listen . . . you must have something, though."

"I told you, buddy, we're cleaned out." "But ..."

The clerk turned away and leaned his elbows on the register, and began to chat again in an undertone with his friend across the counter. The bell-boy shifted his weight patiently to the other foot.

"But listen, though," pleaded the young man incredulously, "you must have something somewhere. We got to go somewheres. This is the only hotel in town . . ."

The clerk turned back to the boy and smiled. "I'm sorry, bud, but we haven't got a thing, I tell you. You should have made reservations before. This is the holidays, see, this is our busy time. Sorry; but."

THE music thudded in the main diningroom above the whisper of dancing feet. The middle-aged man broke the ash of his cigar into a brass spittoon in the center of a rubber mat, and studied the young man casually.

"For God' sakes, you got to put us up somewhere," murmured the young man stupidly. "For God' sakes, there must be something. Haven't you even got a cot or anything? My wife's sick."

"Your wife?" said the clerk.

"What's the matter with her?" asked the middle-aged man, looking across the lobby at the girl in the shawl.

"She's sick. She's . . . not well. Listen," he said in a quick low voice, "can't you see, she's got to get somewheres quick. She's got to find some place to lie down."

"Well, I don't know," said the clerk. "There's the suite upstairs, but we were holding that."

"Thank God you got somewheres. Thank God for that—" His voice faltered and stopped. He dropped on one knee beside the girl, like a priest kneeling before an altar. "It's all right," he whispered to her. "He's got somewheres."

The dark eyes lifted slowly above the shawl to meet his reverent eyes.

He rose after a moment and turned briskly to the clerk: "How much is it?"

"That would be fifteen dollars."

"How much?" The young man looked dully at the clerk, and shook his head. "Fifteen? I haven't got fifteen."

"Well, I'm sorry, buddy, we're all filled up. That's all we got."

"I only got about . . . four or five."

The bell-boy shrugged his shoulders and set down the bags and wandered across the lobby. The clerk closed the register. The music ended suddenly in the main dining-room, and there was a clatter of applause.

"How did you happen to leave home with so little?" asked the middle-aged man.

"We had to come to the city in a hurry," said the young man nervously. "We had to leave home very sudden." He lowered his eyes. "It . . . was about the taxes, see. That was all. I'm registered in this city and . . . We had to see about some income taxes with the government."

"Yeh?" said the clerk, glancing significantly across the counter.

"Yeh, and so that was why we had to come down here so unexpectedly."

"Well, you know you ought not to brought her along in any condition like that," advised the middle-aged man wisely. "You ought to of left her at home."

"I know. I couldn't."

"What's your business, sonny?"

"Odd jobs," quickly. "I did carpenter work, and some repairs, at home."

The man drew on his cigar thoughtfully.

"I'd work hard . . The boy gulped with eagerness. "I'd be willing to do anything . .

"Yeh . . The man clicked two coins together in his pocket, and weighed the boy before him for a moment. "Well . . . it's sure tough, all right." He turned his back abruptly and began to chat with the clerk once more.

The boy stared wildly. "But . . .?"

". . . reminds me of the one, it seems Abie went into a farmhouse and . . ."

"You can't turn us out like this." The boy's voice was a key lower: "You got to do something . . ."

"Sorry, bud." The clerk paused in his story to smile over the shoulder of the traveling man. "If I had a thing I'd fix you up, you know that. There isn't even a cot. I'm telling you."

THERE'S Tony's," suggested the middleaged man to the clerk.

"Yeh, there's Tony's," said the clerk. "It isn't a hotel, but he might let you stay there tonight."

"Where is Tony's?" asked the boy.

"Right down the street to the tracks, and then two blocks to the left," said the clerk. "It used to be a sort of a stable, but he may have fixed it up a little. You can't miss it."

"Go on with the story," said the traveling man..

"Is that all right, dear?" asked the young man, bending over the girl in the chair. "Can you walk that far?"

The dark eyes looked up at him bravely. She rose to her feet.

"Just ask anybody where Tony's is," called the traveling man.

The young man glanced at the bell-boy, and then leaned over and picked up his own suitcase. He supported the girl with his right arm, and they walked to the street door. He set down the suitcase and opened the door, holding it back with his foot as he picked up the suitcase again and helped the girl to the street. The two men were laughing at the clerk's story. The wind blew across the lobby and rattled the imitation red bell.

"Go close the door, boy," yawned the clerk.

Continued on page 116

Continued from page 85

The music had started with a crash in the dining-room.

"Wonder if Tony can put them up," mused the traveling-man.

"They had to leave home so quick," said the clerk. "They must of got in some sort of trouble."

"I don' know." The traveling-man pushed his derby back on his head. "I was wondering. . . . She seemed kind of different."

The clerk grinned: "Tough break for a young couple like that. Tough on them both."

"Mm . . "

"God help the kid."

The girl in the Syrian costume and the Roman senator came down the stairs slowly. They had their masks off, and they were whispering together. They passed beneath the mistletoe, and the old man put his hand against the hard curve of her back, and they danced into the room.

"That little brunette isn't a bad number," smiled the clerk. "Why don't you go in and dance with her?"

"No, I'm too old," laughed the other man, dropping his cigar-butt onto the floor and turning his toe on it. "I'm past that sorta thing. I just like to look."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now