Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowModern Painters

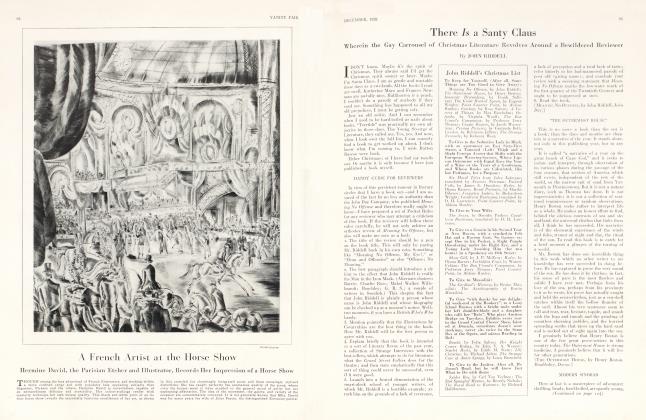

Impressions of a Half Dozen Leaders in French Art Gleaned From a Visit to Their Studios

PAUL MORAND

I ALMOST never see painters, either because I do not like what they are doing, as is usually the case, or because I want to let them work and to make sure that I don't "stand in their light." On visiting a painter in the afternoon, one is always accused of this, as though light were not for everyone. There is of course the evening. But in the evening many painters are still at work, on illustrations and designs; or they have gone off to the country; or they are in their cups—and when away from their studios they lose all poetry. Nevertheless, since I had decided for the purposes of this article to go and spend a few moments with some of the greatest painters of our age, I was obliged to break with my steadfast principles—and I am not sorry that I was.

I had known Andre Derain's quarters at 13, de la rue Bonaparte when the house was nothing but an old Parisian hovel. On the left bank, just opposite the Ecoles des BeauxArts, it was a dirty place, smelling of the concierge's cabbage soup and of tom cats. That was twenty years ago. I went there to pay a visit to a young poet who has since become famous: M. Paul Géraldy. Later, after the war, I was there again to see another painter, Segonzac. I had not been back for eight years. To-day it is brand new, white with green doors, like a house in Schwabing, Charlottenburg, or Chelsea. Theapartments are occupied by millionaire students from Sweden or New York, and bring in fabulous prices. But on the top floor where Derain lives, it is still the same loft inside. A window looks down on a white court cut diagonally by the great shadow of a neighbouring house. At the other end, one of those curious windows on Parisian roofs, held open by an iron rod and known as a tabatière, allows a great patch of intimate Dutch sunlight to fall across a table littered with sketches. Derain is a six-foot giant, with features as powerful and heavy as Napoleon's after the coronation, and blue eyes laden with wisdom and fatigue. He dresses in blue denim like a workman, and his powerful neck emerges from a shirt open at the throat. He has long hair. All around him are chests with negro statues, admirable designs, and rough draughts.

AS a way of breaking the ice, I brought up the subject of automobiles. He has a passion for those little blue monsters called Bugatti which look like trim, vicious bugs. Derain offers me neither a cocktail nor port, but a glass of Avignon wine. Heaven knows that he loves the Midi. Every summer for twenty years he has made a pilgrimmage to La Ciotat or St.-Tropez; but this year Cherbourg and the beaches of the North tempt him. "I don't do much," Derain said to me with a modesty which was belied by the canvases around him. "I go around great subjects. Materially, everything is easy to paint; the problem for painters is a moral one. Who will say how troublesome this man is, who enters with a straw hat on his head . . ." Recalling those delightful canvases of the Ballets Russes, and especially of the Boutique Fantasque, I asked about his interest in the theatre. "It is a joy to paint a stage-setting, to adjust oneself to the many combinations, making the one background suit characters in blue, rose, or green." What interests this realist, this master so well astride of life, who sells his paintings at better prices than any other living artist, what torments him, is the invisible, the mystery of the world's origins. Derain is a great admirer of Sir James Frazer, the primitives, and everything about the artist which is most intangible.

On coming to the edge of the unknown abyss, the frontiers of our destiny, Derain pauses and contemplates the void . . . How paint the void? "The only thing that counts," he says, "is rhythm. If the same head is copied by fifty painters, no two of these pictures will be the same. And of the lot, perhaps only one or two will be worth keeping. These will be the ones with rhythm. Look at Egyptian art: its plastic appeal is not great. How does it live? By rhythm." "Picasso? He is a demon of pride. He is a haughty Spaniard. He never tries to do a thing well; he tries to do it better than others. Matisse? He paints well; yet he does not paint the intimate structure of things, but their exterior. In this however he is a master; he has multiplied our visual approaches immeasurably.-. . ."

MARIE LAURENCIN has the typical young girl's apartment. The canvases which Rosenberg, her picture dealer, has not yet come to collect are displayed on the wall like exercises. (Rosenberg makes his rounds to gather the work of the painters like a farmer's wife looking for eggs in the straw.) There are atlases, skipping ropes, a harmonium, and picture books. This is more of a boudoir than a studio, and more of a nursery than a boudoir. Marie and I were both living in Madrid during the war. But I did not know her then. Yet her paintings of this period, which are less popular and less worldly than her subsequent work and which have won her glory, are perhaps the finest artistically. When I look at the interiors which Marie Laurencin did at this time, I cannot help thinking of the famous prose poem by Baudelaire: "A room like a reverie, a room genuinely spiritual, where the stagnant atmosphere is faintly tinted with rose and blue." Marie adores animals, especially dogs. "I love people,'' she says, "because they are dogs. ' Muff dogs or water dogs, rescue dogs leaping up to protect these ashen-grey girls choked by a ribbon of black velvet about the neck. "I always paint with a little disquietude at heart," she told me. And this is what gives such exceptional sensitiveness to her talent, with its almost monochromatic melancholy. And what wit Marie Laurencin has at her command! What exquisite letters! What charming verses! She has a Parisian tongue—un bon bee de Paris, as Villon, who is always gruff, and always accurate, would say. "Picasso," she says, "is a very malicious somebody. As to diplomats and men of the world, he puts them in his pocket. He is crafty, and never overawed. But he is not a painter. He is from Malaga." Marie Laurencin is also a singer. There is no one like her as she sits at the little harmonium singing folk songs—"Sous les ponts de Paris'' and "J'en ai marre." She also makes a cult of the Bronte sisters and Jane Austen. She has a house not far from Fontainebleau, on the bank of the Seine. She gives you the key, saying, "I should like to go to the country, but I don't have time. You go for me."

Matisse is a man of the North, from Picardy (for France is not confined to Marseilles). He has glasses and a beard, with the coldness of a university professor. What does this master of to-day owe to his time spent at the Beaux-Arts, in the studio of Gustave Moreau? His real masters were chosen by himself—first of all those who reigned at the end of the impressionist school, Signac, Cezanne, and Odilon Redon. Matisse sells abroad, and lives in the Midi. No one is less Parisian. The sunshine of Nice or St.-Tropez floods these rose or green-coloured rooms which he began painting around 1917 and which exhale the joy of living. At times he goes North and paints, after Monet and Marquet, the famous cliffs of Etretat. The location really matters little, for Matisse pursues a personal rhythm. He said, with the simplicity of a great artist: "I do as much as I can as well as I can, working all day. I give my full measure, employ all my resources. And afterwards, if what I have done is not good, I am no longer responsible. The truth is that I can do no better." He is attracted by the Orient. From Oriental tapestries and Arab potteries, he has derived certain blues and reds, and the taste for beautiful arabesques. The jar of goldfish is a theme which he brought from Morocco; his variations on the vases of China are numerous.

ONE must leave France to appreciate Matisse's standing. Three years ago at Moscow I went to see the Morosoff-Choukine Collection, which has become a Soviet museum. And suddenly to my great surprise I found there both the Danse and the Musique, those great colour syntheses which will mark so important a date in the history of modern painting. With their spirit, intelligence, and elevated feeling, they dominated everything else in the Museum. I recalled how as a child I had seen these canvases at the Salon, where they aroused the indignation of the public. At that time Matisse alone understood his aims. He said: "I want an art of equilibrium, of purity, which does not disquiet nor trouble; I want the weary and exhausted to find in my pictures the satisfaction of calm and repose." And posterity will certainly judge him accordingly.

Helene Perdriat, with whom the readers of Vanity Fair are well acquainted, is another young girl, though as different as possible from Marie Laurencin. Their one element in common is the fact that for them painting is an intimate expression and each picture is a mirror. Helene Perdriat is lithe and slender, with black hair worn tight against her head, little black curls at the ears, and an ochre skin. She breathes perfection down to the slightest detail. She has a woman's technical fastidiousness, the French housewife's sense of work done well and conscientiously. In those troubled seas of feminine artists, she has assured herself a ranking of the first importance, thanks to a personality as vigorous as her person is frail.

Continued on page 104

Continued, from page 83

Foujita is the most Parisian of the Japanese. He is a miracle of intelligence, the acme of diplomacy. At Paris, Foujita is an authentic Japanese, with his gold spectacles, his heavy casque of hair, his earrings, his exotic features, and his power of assimilation. But he is also an authentic Parisian, an habitue of the Rotonde, steel-eyed and nervous, who devotes his nights to work or to enjoyment, but rarely to sleep. When I see him squatting àla Japonaise in his studio of the Parc Montsouris, he suggests to me the shoguns of the old novels of chivalry of the school of Kioto. Foujita came to France in 1913, along with the tango; ten years later he had triumphed. His success is feminine. He restores to impressionism all that it had once borrowed from Utamaro. He is the painter of the modern woman; he knows how to render her precisely with her felineness, her perverse brutalism, and her strange simplicity. He also excels in the painting of animals. His picture of the Dogs is among his best, and recalls those dogs of Chelsea porcelain, with curling ears and a gold chain. As to cats, they recur in his works repeatedly, perched on the painter's head or shoulders. While he himself, with his noiseless tread, his striped coat, his eye half-closed, and his brushes between his teeth, always gives the impression of being in quest of a mouse. When, on his ivory-toned canvases which are glazed by a magic preparation, Foujita applies a sure and never retraced stroke, when a touch of wadding he prolongs his delicate immaterial shadows, he displays an art which is simple and per. fidious, a catlike technique.

Picasso. Here the problem becomes complex. "Every picture by Picasso," one art-critic has said, "is a problem stated and solved." This versatile artist, who seeks the new with avidity, and delights in outpacing his imitators, has almost as many periods to his credit as Chinese ceramics. For in the life of Picasso there is room for several ordinary careers. The blue period, the rose period, cubism, the pe. riod of paper cuttings, the period of the bulky heads, bathing women, draperies, et cetera ... To say nothing of his innumerable harlequins and jug. glers, his pastels and his incomparable drawings which bring in prices such as no painter save Derain has ever known in his lifetime. He has often been reproached for taking his materials where he chooses, for plundering the old masters, particularly Raphael, for copying Ingres, and borrowing from the art of Africa. As a matter of fact, Picasso is profoundly creative. With "native and acquired cunning," a trait which does not hamper one's originality, he can bend any previous work to his purposes, though transforming it so thoroughly that it is never anything but Picasso. Visibly influenced by the primitives, most notably by old negro sculpture, Picasso could write in answ'er to a questionnaire: "Negro art? Don't know it." Actually. One day I asked Marie Laurencin what she thought of Derain. "He is a great painter," she said. "And Picasso?" "Picasso," she answered, "is a great mind."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now