Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

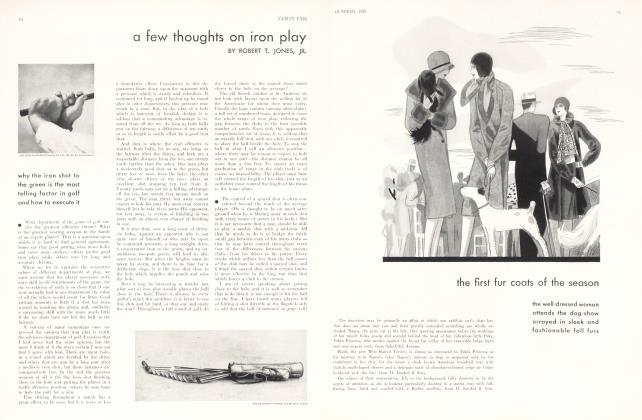

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Most Difficult Part of the Game of Golf

Being a Few Friendly Counsels by the British Open and American Amateur Champion

ROBERT T. JONES, JR.

EDITOR'S NOTE:—Having read with some attention what Bobby Jones has written on golf, during the past year or two, Vanity Fair has collected certain notes of his on iron play, on wooden play, and on putting, and has published them as consecutive articles. The following paper—the third, in the series to be published in these pages—deals with the problem of putting. The article is published by permission of the Bell Syndicate, Incorporated.

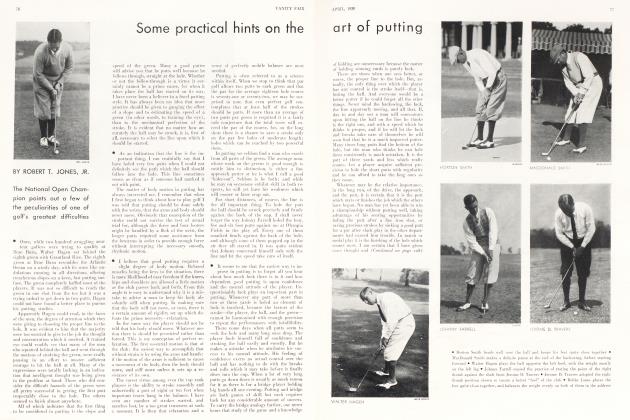

THE most difficult part of the game of golf is played on the putting green, and yet most men will practice and take lessons with every club except the putter. A few casual taps while waiting for their starting time mark the extent of the practice that most of them will indulge in. And putting is an art which can be acquired only by constant and intelligent work. A person can be taught how to swing a putter properly, but he seldom can be taught how hard to hit the ball, or how much he must ''borrow" from a slope of the green. All this can be learned only through practice and experience, and lots of it.

I suppose every golfer in the world must have wondered why he can play golf one day without missing a single holeable putt, while, on the very next round he will find himself unable to hole out from the shortest distances.

For a long time now I have worried and fretted myself trying to develop a putting style which would enable me to putt well every day. I have tried, in other words, to reduce my play on the greens to a scientific and unvarying basis upon which I could always depend.

NOW Clarke Corkran thinks that the only important feature of the putt is the stroke, and the hitting of the ball. His idea is that if a man could acquire a sound stroke, and would practice it until he could produce it every time, he could putt well every day. So, when Clarke practices putting, he gives no attention to the hole nor to where his ball may finish. His entire concentration is upon hitting the ball.

Now I admit that the stroke is important, for, obviously, the ball cannot be started on the proper line if the club-face is askew at the time of hitting. But I also believe that many of us do give too much thought to the way in which we take the club back, to the position of the wrists and, finally, to stroking with the right hand.

Mechanically the putting stroke is the simplest of all strokes. There are no difficult lies on the putting green and there are no problems of pivoting and elbow action to contend with. It would seem, therefore, that we ought to be able, without much trouble, to swing a putter in reasonably accurate fashion if we have any aptitude whatever with a golf club.

My own experience in this respect seems to be typical. For many years I tried to imitate Walter Hagen, or Freddie McLeod and other good putters, but I could never attain any satisfactory consistency on the greens until I abandoned all my imitations and began to take my own natural position and to swing the club in my own peculiar way. Several months ago I made up my mind that, regardless of how it was done, the important thing in putting was to get the ball into the hole.

I still practice putting, just as I practice all my shots, but I don't do it for the same reason. When I go out to work with my irons or wooden clubs I do so because there is a fault in my swing that must be found out and corrected; but when I have a session with Calamity Jane I do not give a thought to the way she is swinging.

My thought is rather to acquire the two essentials of good putting—touch and confidence. By touch I mean the indefinable something which unconsciously gives the proper strength to the blow. It is the result of a coordination of the delicate mechanisms that dwell in the mind and nerves. It cannot be taught. Possibly it cannot ever be acquired by all people. Some days we have it and some days we don't: but we cannot putt well without it.

CONFIDENCE is a great quality. It is easily recognized but hard to cultivate. I am sure that it constitutes fifty per cent of good putting. I have many times holed prodigious putts and chip shots when I felt, before I addressed the ball, that I was going to do so. Often I can see the complete line which my ball must take to the hole. The exact line appears to be drawn out for me. And I don't seem able to remember instances when I missed one of those putts. Often I have thought that I could be a better putter if I could only wait on my putts, and look—look until I could see the line of every putt. But it doesn't work that easily. It takes something more than waiting and looking. We have all had days when we could have putted well with any sort of a club from any position and with any stroke. We simply feel that we can sink them and we do.

One's state of mind unfortunately cannot be controlled. We cannot have confidence because we wish to have it. But we can cultivate a determination to hole every putt and we can forget everything else except putting the ball into the cup.

I know well that I do not take the same stance on every putt and that I do not always grip my club at the same point. I am certain that my putting has improved as a result of not concentrating too much about my stroke.

Once, while playing a friendly round, I became aware of a defect in my putting methods which, I believe, had been largely responsible for my erratic work on the greens during the previous year or so. And because I think the defect is one into which all golfers are likely to fall, I want to call it to the attention of those who may read this paper. The mistake is so simple, the error so trifling, that you may be, as I have been, many times guilty of it without having the least suspicion of the root of the evil.

I had been playing at East Lake with Charlie Black, one of our very best young golfers. I have always regarded Charlie as one of the most deadly putters I know, a player who putts, not merely well, but brilliantly and at all times. I have watched him closely for a long while, trying to discover just what he did that made his ball seem continually to be seeking the bottom of the cup. This day I found out what he did or, rather, by watching him, I found what I did not do. When addressing his putt, Charlie, placing almost his entire weight on his left foot, pushed his hands so far forward that they were in front of his left leg, almost immediately beneath his left shoulder. The ball was opposite the left foot but appreciably behind the hands.

Of course there is nothing startling in the observation that the hands should be in front of the ball when addressing it. That point is, I think, very generally recognized. The great difficulty is that, in watching for less obvious mistakes, we are apt to overlook what is before our very eyes. For over a year I had had no confidence on the putting green. I was told repeatedly that my stroke looked quite all right and that I should have no trouble if I would only stop worrying about it. But I always felt that I wasn't striking the ball a sharp, solid blow. One putt would be halftopped, another pushed, another hit much too hard, and so on. I changed my putter, altered my stance, did everything I could, except to move my hands forward.

ONE effect of keeping the hands back is to force the putter-head outside (on the back stroke) unless there is a considerable movement of the body. This will not be disastrous on the long approaches, where more freedom is allowed, but it will be ruinous on putts of ten and fifteen feet—just the kind you feel you ought to hole. Also there is great danger that the left hand may not move forward out of the way and will begin to throw the club head upward before it reaches the ball, which will invariably cause the putt to be half-topped.

With the hands out in front the arms are free to move—and they should be used—and the club is somehow under much better control. From this position a clean, firm blow may be struck with the assurance that no protruding knee or belt buckle will interfere. Both hands can work together in a comfortable fashion.

When I think of good putters, I inevitably begin with Walter Hagen, probably the very best of them all. If you will watch Walter addressing his putt, you will notice that his hands are touching the crease in his left trouser leg, and that the greater part of his weight is on the left foot. And the same with Johnny Farrell, another very fine putter. Johnny, however, makes his stroke almost entirely with his wrists, while Walter makes a quite noticeable use of his body and arms.

There is no need to multiply examples. Every good putter I know keeps the hands well in front, so I think there can be little doubt that it is a good practice. My own experience enables me to say with certainty that to keep the hands behind the ball is a really pernicious fault.

(Continued on page 100)

(Continued from page 80)

One last thought onputting. I should like here to mention what I think is a mistaken idea. We have all heard the expression,—"Never up, never in"— and, "Well, I gave that one a chance, anyway,"—used as excuses for considerably over-running the hole, and many golfers feel that their duty is well done if, when confronted with an important putt, they hit the ball well past the cup. They don't stop to think that, for a ball going fast, the hole is really only an inch wide— that is, the very center of the hole must be hit—while if the speed is right, the ball may go in at the front, back or side of it. Suffer the ignominy of being short if you must, but try to roll the ball just up to the middle of the cup. Then many putts that are not precisely on the line, will drop in.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now