Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Importance of Holing the Short Putts

Being More Helpful Suggestions Advanced by the British Open and American Amateur Champion

ROBERT T. JONES, JR.

EDITOR'S NOTE: Vanity Fair here presents a few of Mr. Jones' theories on putting, published by permission of the author and of the Bell Syndicate, Inc.

OF THE last eight United States Open Championships—all that I have ever played in or watched—only two have been won by a greater margin than one stroke. Three of the last five have resulted in ties necessitating play-offs to determine the winner. On one occasion, at Worcester in 1925, the first play-off likewise resulted in a tie, and the winning margin in the second was one stroke.

When championships are won by one stroke, over a seventy-two hole test, it becomes a difficult matter to say just where that one stroke was gained. One stroke in four rounds means, of course, one-quarter of a stroke per round, a difference that is almost infinitesimal and yet tremendously important.

In a competition of this kind, if we could make a careful stroke-by-stroke analysis of the play of the first four or five finishers, I believe we should be able in almost every case to account for the ultimate margin within a radius of four feet from the hole. If we could go back and concede every putt within that circle to the man who finished second or third, he would likely prove the winner with strokes to spare. Of course that might be carrying things a bit too far, for although a four-foot putt appears simple enough to the gallery, it is rarely that even an expert can go eighteen holes without missing at least one of them.

But the wasted stroke is not the only evil consequence of a lapse in putting. Very often the player's confidence and courage will be so shaken that his entire game will collapse utterly.

TO miss a putt of two, three, or even four feet seems about the most unnecessary thing in the world. The texture of most of the greens upon which great competitions are played is such that no valid excuse is offered the player. In almost every case, one may have the assurance that, if struck properly, the ball will find the bottom of the cup.

The greatest difficulty in the short putt arises from the fact that, if we allow for the roll of the green, the stroke must be very delicate and the blow very gentle because of the meager space to be traversed. To strike a crisp and firm, and at the same time gentle blow, requires the very last degree of what we call touch, and firm hitting is the essence of good putting.

But for the putter of less extreme delicacy there is always open the method of spanking the ball into the back of the cup. Indeed, where there is a bit of roll to the green, I think that is the best method. If we endeavour to borrow, on a short putt, there is always the danger of an error in gauging the speed which will be sufficient to allow the ball to fall off below the hole, or if we have hit it too hard, to keep it from taking the fall until it has passed the cup.

The mental attitude in which we approach a short putt has a lot to do with our success. When we walk up to a putt of ten or fifteen feet, we are usually intent upon holing it. We know we shan't feel badly if we miss, so that our entire attention is devoted to the problem of getting the ball into the hole. But it is quite different when the putt is only a yard long. Then we know that we ought to hole it easily, and yet we cannot fail to recognize the possibility of a miss. Instead of being determined to put the ball into the hole, we become consumed with the fear of failing to do so. Our determination, if we may call it such, is negative. We are trying not to miss the putt, rather than to hole it.

I was once playing with Leo Diegel in an open tournament in Atlanta. Leo and I were having as much fun trying to beat each other as we were in trying to win the tournament. In the second round Leo had a putt of less than a foot to beat me by one stroke on that round. The grass around the hole, Bermuda, by the way, was bristly and stiff, and I could see, as Leo stepped to putt, that he was intent upon hitting the back of the cup. Concentrating upon his purpose he hit the ball much too hard, and it passed over the hole without a bobble, running at least four feet beyond. I really did not expect him to hole the next one, but he did, and we finished all even.

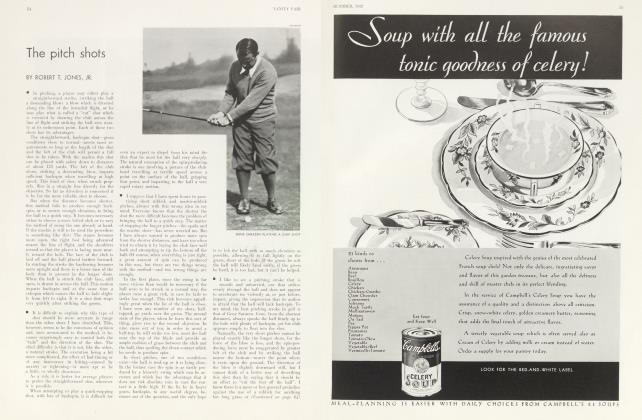

HILE I favour a free, sweeping swing for putting at middle and long distances, I do not believe that this method is reliable for the shorter ranges. The sweeping stroke is primarily one of delicacy, and delicacy is not so much desired on the short putts as direction. I think the best method is to take a short grip on the club and get your head down a good deal closer to the ball. I should also grip the club a bit tighter and strike the ball with a firm left wrist. The first necessity in holing short putts is to keep the putter blade from turning away from the line. (In this connection, I should like to observe, from my own experience that the iron putter, preferably a goose-neck, is infinitely more reliable than the aluminum variety. Somehow, with a putter of that sort I cannot keep the ball from sliding off to the right, probably because I am not able to get as nearly directly above it while addressing the ball.)

There is no possibility of exaggerating the value of being able to hole all the short or really easy putts. It isn't necessary to hole the long ones if the little ones are certain. I can recall match after match and tournament after tournament which might have been saved by holing a few short putts. And I know that I am not the only one who must repent errors of this kind, for almost every runner-up has missed enough putts under six feet to make him an easy winner if he had holed them all.

In 1923, Arthur Havers and I played a match for what some ambitious folk were pleased to term the "unofficial world's championship". Havers had won the British Open that year, and I the American championship. We had it nip and tuck most of the morning. But, in the afternoon, we turned for home with Havers four up. Then holes began to come back to me, until I stood (on the sixteenth tee) one down. We both played the hole terribly, he being short in two, while I pulled my second to a deep bunker at the left of the green. Finally I played out two feet from the hole and was left with that putt to even the match. And I missed it. I lost the next hole with barely a struggle and finished two down with one to go.

Again at St. Louis I had a similar experience, only worse. Playing against Willie Hunter, I had lost my scant advantage of one hole when Willie holed a three at the fourteenth of the afternoon round. At the fifteenth he holed a ten-footer for a four and I missed a two-footer for the like. I lost that match on the seventeenth also.

That was two against me. But there is usually some consolation in the darkest cloud. It was only by two very short putts, which Al Watrous missed on the fifteenth and seventeenth at St. Anne's, that I won my first British Open.

I used to be a very rapid putter. I am still fairly fast after I have once taken my stance. But at Merion in 1925 I discovered that I was missing a lot of putts simply because I was hitting the ball too soon after I had reached the green. Having walked up to the green at a brisk pace and elbowed my way through whatever gallery there might be, I had been putting quickly while my breath was coming in short gasps and my ears were ringing as I leaned over the ball.

REALIZING that I was making a mistake I resolved that no matter how much time I consumed I was going to tranquillize my breathing before I made another putt. So I began to take great pains to study the line. I really did not study the line very much, (for I have never been able to see more rolls and bumps in a minute than I could in five seconds) but I was giving my breath a chance. You have no idea what a steadying effect it has on the nerves to do some little thing on the green in a casual manner. Light a cigarette, pick up a twig, or anything at all to take up a little time.

Another thing that oftens helps. When you have located the line to the hole and addressed the putt, it often happens that something gets blurred and you lose the line. Don't go ahead and putt then for you will surely miss it. Step away and start all over again. You didn't have a chance at first; you might make it now.

Putting is the only department of the game in which I should recommend making a radical change during a round. The putting stroke, while not always manageable, is nevertheless the simplest in golf and more readily subject to adjustment than any other. And, somehow, no change short of a complete one seems to aid our difficulties on the greens.

It has always been my idea that good putting is in a great degree dependant on confidence and luck. Every golfer, I am sure, recognizes the fact that he can putt well if he can only make himself believe that he will. So, to cure bad putting the problem is to find a style which will give one confidence.

(Continued on page 114)

(Continued from page 86)

I am unable to assign a reason for a fact which I know to exist, namely that a sudden alteration in putting methods often brings improvement.

To illustrate the kind of change I suggest making I might consider my own case. Normally, when putting, I stand fairly erect, grip my putter very near the end with my hands drawn up a little bit, and take a long pendulum-like swing. My purpose as a rule is to sweep the ball along with a stroke as even and unhurried as possible.

But on some days this system is no good and something has to he done immediately. The first thing I try is to turn my body toward the hole, facing around, while addressing the hall, until I am looking almost toward the cup. Sometimes that will be just the needed correction. Almost always it will remedy errors in distance. But: it rarely helps on the "holing-out" variety of putt of four, six and eight feet.

To hole every putt, no matter how short, would consume a great deal of time in the course of an eighteen hole round, and where congestion is bad enough anyway, there ought to be nothing to make progress slower. Missable putts, of course, should not be conceded, for they are as much tests of skill as any other shots in the game, but when there is no reasonable possibility that the putt will be missed, I think the ball should be knocked away and the next hole played.

George Von Elm shared with me at Baltusrol a modicum of official displeasure for certain concessions we had made each other with the best of intentions. On the seventeenth hole of our final match, I left George to make a short putt for the half. It was not a hard putt, but neither was it one which I felt like giving him. But as George addressed his ball the crowd started running for the next tee, and he stepped back to let them settle. I knew he could not miss it if given a fair chance, and as there seemed no likelihood of the crowd quieting down, I knocked his ball away. At the next hole, I was left in the same situation.

It seems to me that the general practice is the best; namely, to concede only those putts which are reasonably certain to be made, but to concede all of those. It is folly to insist that it is possible to miss a putt of six or eight inches, or even of a foot.

And here a word or two might be added concerning the chip-shot. In playing a chip-shot or a putt, the range or speed of the rolling ball is most important. The ball must be struck a true blow every time if there is to be any means of controlling its run. To top or half-top this one, to hit the turf behind the next, soon produces an uncertainty which leaves the player in a quandary as to how hard he should swing his club.

A lot has been said and written about the part played by the wrists in executing a chip-shot or putt. Each of these strokes has often been described as being made entirely with the wrists. Following this advice, or possibly because of a natural inclination to scoop the ball, the player swings his run-up club or his putter, from start to finish without moving his arms. The segment or arc, therefore, described by his club-head is of very small radius— descending sharply and ascending sharply. There is then only one point at which he can hit the ball when the club will strike it properly, and that point is the very bottom of the arc. If the stroke is not exact—the lowest point in the path of the clubhead will be reached somewhere back of the ball and the club will either strike the ground, or, rising quickly, will half top, or top, the shot.

The cure of course, is to take the ball while the club is descending and to flatten the path of the club. By this I mean that, playing a chip or putt, the club should finish near the ground, having travelled from impact almost horizontally instead of upward.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now