Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSome practical hints on the art of putting

ROBERT T. JONES, JR.

The National Open Champion points out a few of the peculiarities of one of golf's greatest difficulties

• Once, while two hundred struggling amateur golfers were trying to qualify at Brae Burn, Walter Hagen sat behind the eighth green with Grantland Rice. The eighth green at Brae Burn resembles the Atlantic Ocean on a windy day, with its wave like undulations running in all directions, offering treacherous slopes on a keen, fast putting surface. The green completely baffled most of the players. It was not so difficult to reach the green in one shot from the tee but it was a trying ordeal to get down in two putts. Hagen could not have found a better place to pursue his putting studies.

Apparently Hagen could read, in the faces of the men, the degree of attention which they were giving to choosing the proper line to the hole. It was evident to him that the majority were too worried to give to the job the thought and concentration which it merited. A trained eye could readily see that many of the men who squatted behind the ball and went through the motions of studying the green, were really pausing in an effort to muster sufficient courage to hit the ball at all. Many of the expressions were totally lacking in an indication that intelligent thought was being given to the problem at hand. Those who did consider the difficult hazards of the green were all pretty successful in getting the first putt respectably close to the hole. The others seemed to finish almost anywhere.

All of which indicates that the first thing to be considered in putting is the slope and speed of the green. Many a good putter will advise you that he putts well because he follows through, straight at the hole. Whether or not the follow-through is a virtue it certainly cannot be a prime cause, for when it takes place the ball has started on its way. I have never been a believer in a fixed putting style. It has always been my idea that more practice should be given to gauging the effect of a slope and to estimating the speed of a green (in other words, to training the eye), than to the mechanical perfection of the stroke. It is evident that no matter how accurately the ball may be struck, it is, first of all, necessary to select the line upon which it should be started.

• As an indication that the line is the important thing, I can truthfully say that I have holed very few putts when I could not definitely see the path which the ball should follow into the hole. This line sometimes seems as clear as if someone had marked it out with paint.

The matter of body motion in putting has always interested me. I remember that when I first began to think about how to play golf I was told that putting should be done solely with the wrists, that the arms and body should never move. Obviously that conception of the stroke could not survive the test of actual trial for, although the three and four footers might be handled by a flick of the wrist, the longer putts required some assistance from the forearms in order to provide enough force without interrupting the necessary smooth, rhythmic motion.

• I believe that good putting requires a slight degree of body motion. Relaxed muscles being the keys to the situation, there is more likelihood of easy freedom if the knees, hips and shoulders are allowed a little motion as the club passes back and forth. From this angle it is easy to understand why it is a mistake to advise a man to keep his body absolutely still when putting. In making sure that the body will not move, or turn, there is a certain amount of rigidity set up which defeats the prime necessity—relaxation.

In the same way the player should not be told that his body should move. Whatever motion there is should be permitted rather than forced. This is my conception of perfect relaxation. The first essential motion is that of the club; the easiest way to accomplish that without strain is by using the arms and hands; if the motion of the arms is sufficient to cause a movement of the body, then the body should move, and will move unless it sets up a resistance of its own.

The rarest virtue among even the top rank players is the ability to stroke smoothly and unhurriedly a putt of eight or ten feet when important issues hang in the balance. I have seen any number of strokes wasted, and matches lost, by a too great tenseness at such a moment. It is then that relaxation and a sense of perfectly mobile balance are most needed.

Putting is often referred to as a science within itself. When we stop to think that par golf allows two putts to each green and that the par for the average eighteen hole course is seventy-one or seventy-two, we may be surprised to note that even perfect golf contemplates that at least half of the strokes should be putts. If more than an average of two putts per green is required it is a fairly safe conjecture that the total score will exceed the par of the course, for, on the long shots there is a chance to save a stroke only on the par five holes of moderate length; holes which can be reached by two powerful shots.

In putting we seldom find a man who excels from all parts of the green. The average man, whose work on the greens is good enough to entitle him to distinction, is either a fine approach putter or he is what I call a good "holer-out". Seldom is he both; and while he may on occasions exhibit skill in both respects, he will yet have his weakness which will sooner or later crop out.

For short distances, of course, the line is the all important thing. To hole the putt the ball should be struck precisely and firmly against the back of the cup. I shall never forget the way Johnny Farrell holed the four, five and six foot putts against me at Olympia Fields in the play off. Every one of them smacked firmly against the back of the hole, and although some of them popped up in the air they all stayed in. It was quite evident that Johnny concerned himself only with the line and let the speed take care of itself.

• It seems to me that the easiest way to improve in putting is to forget all you hear about how much luck there is in it and how dependent good putting is upon confidence and the mental attitude of the player. Unquestionably luck plays an important part in putting. Whenever any putt of more than two or three yards is holed an element of luck is involved, because the factors of the stroke—the player, the ball, and the green— cannot be harmonized with enough precision to repeat the performances with infallibility.

There come days when all putts seem to seek the hole and many long ones drop. The player finds himself full of confidence and stroking the ball easily and sweetly. But he makes a mistake when he attributes his success to his mental attitude. His feeling of confidence exerts no actual control over the ball and has nothing to do with the breaks and rolls which it may take before it finally dives into the cup. When a lot of very long putts go down there is usually as much reason for it as there is for a bridge player holding big hands all one evening. Putting and bridge are both games of skill but each requires luck for any considerable amount of success. To carry the bridge analogy farther, one never hears that study of the game and a knowledge of bidding are unnecessary because the matter of holding winning cards is purely luck.

There are times when one sees better, or worse, the proper line to the hole. But, actually, the only thing over which the player has any control is the stroke itself—that is, hitting the ball. And everyone would he a better putter if he could forget all the other things. Never mind the hackswing, the luck, the line apparently moving, and all that. If, day in and day out a man will concentrate upon hitting the hall on the line he thinks is the right one, and with a speed which lie thinks is proper, and if he will let the luck and breaks take care of themselves he will soon find that he is a much improved putter. Many times long putts find the bottom of the hole, hut the man who thinks he can hole them consistently is much mistaken. It is the putt of three yards and less which really counts. Let a player acquire sufficient precision to hole the short putts with regularity and lie can afford to take the long ones as they come.

Whatever may he the relative importance, in the long run, of the drive, the approach, and the putt, it is certain that it is the putt which mars or finishes the job which the others have begun. No man has yet been able to win a championship without putting well, taking advantage of his scoring opportunities by holing the putt after a fine iron shot, or saving precious strokes by sinking a good putt for a par after slack play in the other departments had caused him trouble. In match or medal play it is the finishing of the hole which counts most. I am certain that I have given more thought and attention to chipping and putting than to all other departments of the game combined, and I suppose it took me longer to acquire proficiency there than in any of the others. Form in golf varies greatly from day to day in every respect, from the driving on down, but I think it is harder to putt consistently well than it is to do anything else in the game.

Continued on page 108

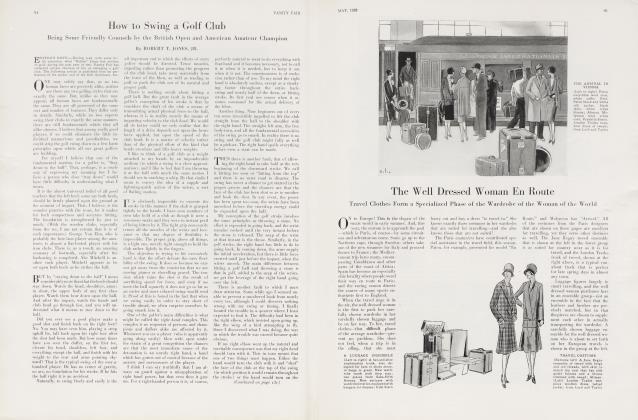

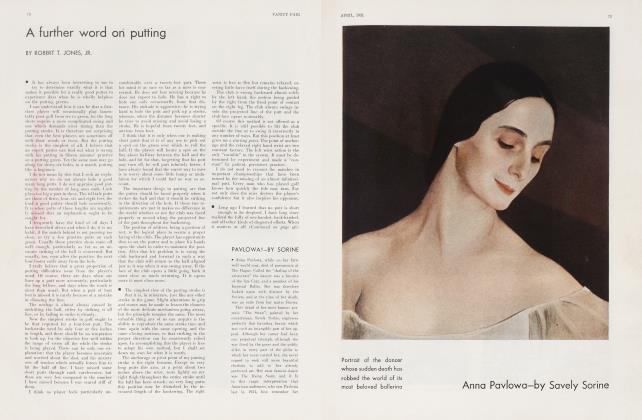

• Horton Smith bends well over the hall and keeps his feet quite close together • MacDonald Smith makes a definite pause at the end of the backswing, before starting forward • Walter Hagen plays the ball opposite the left heel, with the weight mostly on the left leg • Johnny Farrell copied the practice of resting the point of the right thumb against the shaft from Jerome D. Travers • Jerome D. Travers adopted the right thumb position shown to insure a better "feel" of the club • Bobby Jones places the feet quite close together, and balances the weight evenly on both of them in the address

(Continued from page 77)

The main thing is to be comfortable, thoroughly relaxed, with no hint of strain. This is highly important. There is nothing more important than a smooth, evenly accelerated stroke. There must be a firm crisp contact, of course, but the sharpness of the blow must not be obtained by quickening the motion of the club too suddenly. This is exactly what happens if the backswing be too short. Even the necessity for the slightest extra effort will infallibly produce a jerky, uneven stroke and swing the ball off line. The hole is such a small target to shoot at from thirty or forty feet that the slightest mis-hit is very apt to cause an expensive error. I think more good putters have been ruined by attempting to duplicate another man's method, than by any other single factor. By the time they can place themselves in a position which they think resembles the attitude of the other man they find themselves so cramped and strained that a smooth, rhythmic stroke is impossible.

There are two things which I continually do wrongly on the putting green: first, to allow myself too short a backswing and, second, to look up before I hit the ball. Whenever my putting goes wrong these are the first places to which I look to find the trouble.

The looking up habit makes the putts stop short of the hole.

It will be noticed that most of the really fine putters in the game today favor the old iron putter, and most of them use the goose-neck variation. This variation is supposed to have been suggested by an untoward accident to Willie Park's favorite putter when a heavy wagon passed over it. There is one thing, however, which applies to every man, no matter what putter he chooses. He should know his club and never discard it if he can avoid doing so. When he has an off day he should remember the days when he has putted well with it and realize that the putter will likely perform as well again if handled as skillfully. Sometimes when confidence has been shaken, it helps to use a new putter for a round or two, until a few putts begin to drop and the player's morale has improved. But in the long run the old horse is the best.

EDITOR'S NOTE: This is one of a series of golf articles by Robert T. Jones, Jr., and is published with the consent of the 'Bell Syndicate, Inc.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now