Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHOOVER'S "REMOTE CONTROL"

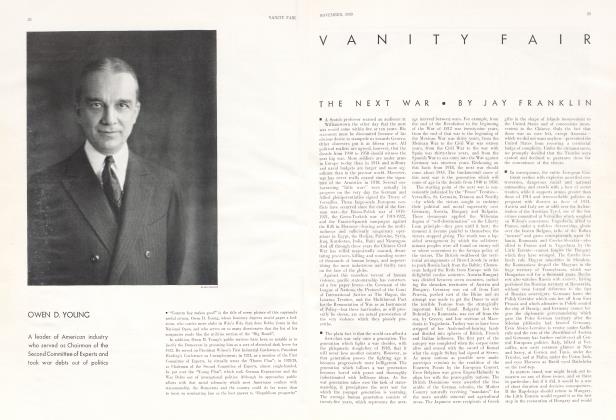

JAY FRANKLIN

■ Back in the dark ages when Al Smith was

the wet hope of drinking people and when Herbert Hoover was reluctantly announcing that Prohibition had been a great social experiment noble in motive, one of the political engineer's secretarial safety-valves outlined the Republican nominee's scheme for running these occasionally United States.

"The Chief," he said, "is going to run this country just as though it was a great big corporation. None of this hand-shaking stuff for him."

"And the Senate?" remarked his interviewer cynically.

"Hoover's going to use public opinion to make the Senate do as he wishes," was the astonishing reply.

In view of the large political X which marks the spot where Woodrow Wilson exceeded the Senatorial speed limit, the interviewer observed that he didn't believe in Santa Claus. The secretarial safety-valve shortly thereafter did a nose-dive out of politics into Big Business and the interviewer thought no more about it until a year later he heard a press agent for what was left of the Democratic Party complain bitterly that no matter what happened, Hoover's friends always claimed it was exactly what Hoover wanted.

The fact is that the engineer-in-politics is running his Administration as though it were a big business and he has as his model, not Judge Gary's steel monopoly, but Sam Insull's utility combine. Hoover has imitated the latter's pervasive publicity machine until now he has actually outflanked the Senatorial opposition which makes every President's career a cross between a sword-dance and a paperchase.

■ The Senate naturally feels pretty bitter

about this and holds to the fond hope that the public is tasting wormwood too. The people who voted for Hoover thought that they had chosen a man who would make Borah stand up on his hind-legs and bark for his biscuits and who would put Hiram Johnson through the hoops. People like a sporting element in politics and no small part of the Senate's prestige is due to the fact that a good dog-fight between the executive and legislative branches requires a strong Senate.

As American politics are constituted every Republican Senator carries the Presidential baton in his political knapsack. This means that the Senate spends the greater part of its time setting booby-traps for the existing Executive. To combat them the latter has two great weapons. The first is unity of command. He operates on interior lines and can act while the Senate argues for the record. The second is patronage. The offices (postoffices, collectors of internal revenue, collectors of customs, collectors of Prohibition enforcement, Federal judgeships, attorneyships and such) are the life-blood of politics. A skilful President can play Senators with patronage like a xylophone and croon happily at the same time. The only trouble with this political orchestration is that when election time comes around there is no overwhelming clamor for an encore. So the President has to sell himself to public opinion at the same time he is playing hot-hands with the Senate.

This is a problem which every President must solve for himself. Not even his best friends will tell him. Roosevelt did it by waving the Big Stick, using "short, ugly words" and behaving generally like a hookand-ladder company en route to a five-alarm fire. Bill Taft just kept beaming along, singing in the political deluge which left the Republican Party water-logged for eight years. Wilson referred every issue to the moral sense of the American people. He preached infant damnation in politics and we were still close enough to Fundamentalism to prefer sermons to statesmanship. Harding got on with the Senate because he was a Senator at heart and gave away his political shirt to the neediest Senatorial cases. Coolidge got on with the Senate by keeping out of its way and laying a veto every so often in the political henroost just for the sake of the record.

Hoover's problem is more difficult. He lacks Roosevelt's magnetism. He lacks Taft's geniality. He lacks Wilson's moral self-righteousness. He resembles Harding in nothing except his literary style, which is a peculiar blend of Vizetelly and sentimentalism. He does not resemble Coolidge in any respect. He is respected, he is trusted, he is admired—and he excites about as much enthusiasm as a derrick.

His solution of this problem has been masterly. Unable to achieve popularity, he has set out to create public opinion. Unable to command political loyalty, he has set out to enforce it by means of world-wide publicity. Faced with rebellious party leaders, he has revived, unofficially, the Committee on Public Information, an institution which changed Woodrow Wilson from an academician to a Messiah and America from a nation to a moral epidemic. Hoover has organized publicity in behalf of his policies as adroitly as Insull did his propaganda for the private ownership of public utilities; he has invented a new technique of political leadership by "remote control" which has baffled the neolithic Senators who want him to come out and fight like a man.

The elements in the Hoover Committee on Public Information are simple. The first, though not the most important, is the team of pet journalists who went dry with Hoover in more ways than one, who play medicine ball with the Chief, and broadcast over syndicates and radios the Hoover policies. Hoover picked them for their independent following, they are on the whole men who did not have to take orders from any central office, men whose work had authority: Bill Hard, the bad boy of the fight against the League of Nations, the savage independent whose Hooverism has left an empty niche in The Nation; Frank Simonds, the best of our publicists on foreign relations and the most virile of Yankee nationalists; Mark Sullivan, the author of Our Times, dean of Washington correspondents, the reporter who swallowed the Washington Conference hook-line-and-sinker, the best political forecaster in America; Wilmot Lewis, the lanky correspondent of the most important paper in the world, The London Times, the man who did more than the British Embassy to keep Anglo-American relations on an even keel during the Geneva Naval Conference, the man who can do most to give Hoover a good press in the British Empire. On a slightly lower plane stand such figures as Dick Oulahan, the supple correspondent of The New York Times, who walks the daily tightrope of Hooverism on a Democratic daily and Alva Johnson, the interchangeable reporter of The New York Herald-Tribune who has been given the tough job of explaining away the "I will appoint a Commission" business which is to Mr. Hoover's technique what "May I not?" was to Wilson's oratory.

■ This Commission business is a difficult

thing to explain because the fact-finding commission is the key element in the Hoover propaganda. It prevents committing him on controversial questions while it supplies the public with talking points for a political freefor-all. This enables Mr. Hoover to congratulate the winning side in any quarrel and to tell the loser that he put up a fine fight. The third element in the new "Compub" is exerted through the recently established Business Council, set up as the secular arm of the Chamber of Commerce. Instituted to combat economic defeatism in the dark days when Wall Street went tickertape, it was really an integral part of a carefully devised plan to solidify commercial support for Executive policies. And finally there is the mopping-up squad of publicity experts in every government department, not only those who prepare press releases and glad-hand the newspaper boys, but those who analyze results. Every day the White House receives detailed analyses of newspapers, both news stories and editorials, foreign and domestic, bearing on Presidential policies. Such fine points as position, headlines and the political affiliation and daily circulation of the paper displaying them are included. From day to day, Mr. Hoover is able to chart the advancing lines of his drive on public opinion. It is a thoroughly scientific process.

Continued on page 112

(Continued from page 41)

And it works. Three separate incidents illustrate its efficacy in relation to naval disarmament, tariff reduction and last, but not least, the renomination in 1932. At the time, the Shearer investigation looked foolish, like killing flies with a 16-inch gun. The little naval propagandist for the ship-builders may not have been "the man who wrecked the Geneva Conference"; there can be no question that he was butchered to make a naval holiday. The result of Shearer's brutal clubbing by the experts of a Senatorial investigation was to brand in advance all opposition to disarmament as propaganda for the Bethlehem Steel Corporation. Admirals, Daughters of the American Revolution, veterans and even unprofessional patriots had to shut up after Shearer had been shorn. Better still, the pacifists were likewise in terror of an investigation and collapsed in obsequious silence at the feet of Mr. Hoover and his strongarm squad. Check.

Next. The original Hoover purpose was to play the Senate against the House high-tariff rates, just as he had previously played the House against the Senate on farm relief. Unfortunately, Senator Smoot tried to enact the Himalayas into the tariff law, so Hoover fell back on his next line of defense. Borah swallowed the bait offered by the Shearer lobby inquiry and set about investigating tariff lobbies. This was splendid. The wicked industrial lobbies were unmasked, also the virtuous agricultural lobbies. The investigation backfired. The public got an idea that high duties meant high prices and pop went the weasel. For three weary months the Senate has been eating its words. If you watch the votes you'll find that whether the "Coalition", the "Old Guard" or the "Young Turks" win, the result is nearly always a lower duty. Check and double-check.

The third illustration is deceptively simple. Hiram Johnson naturally hates to see a fellow-Californian in the White House. Johnson controls California state politics and through them the delegates to the next Republican convention. Johnson has staked his political life on Boulder Dam. It's his strongest card. His weakest card is the Governorship. The Hoover crowd are trying to take the Governorship away from Johnson's man. If they succeed, they can get the delegates for Hoover in 1932; if not, Hoover (whom the Old Guard hopefully call "a oneterm President") will have hard sledding. Neither side wishes to draw the sword first but matters approached a show-down at Christmas when Johnson justified support of his Governor on the ground that the latter had "stood by his pledges on Boulder Dam". Thereupon, Senator Smoot introduced a bill to change the name of Boulder Dam to "Hoover Dam". A variation of the old idea that so long as you can write a nation's songs, its laws won't be enforced. This is a neat stroke of publicity, which has turned Johnson's best weapon against him.

Hoover's goal, of course, is 1932. A President's first duty is to get himself reelected. The Old Guard love him about as much as they would strict prohibition enforcement in the District of Columbia. "Anything to beat Hoover!" is still their war song and Calvin Coolidge is the man who knows how the chorus goes. He has frankly admitted that he does not think the Third Term convention applies to him, he has publicly expressed his admiration of and gratitude for the Senate and he has carefully evaded all attempts to put him in the Senate. Charlie Hughes has been railroaded into the Supreme Court, Dwight Morrow has been persuaded to represent New Jersey in the upper house, but Calvin believes in political predestination and may quite possibly choose to run in 1932.

The Senators don't like Hoover in the White House. They wouldn't like the Archangel Gabriel in the Executive Mansion. They resent the publicity mumbo-jumbo by which Hoover's remote control over their legislative activities forces them to do what he has made the public think it wants done. Their turn is coming. They too control public opinion, of a local nature, but sufficient for their purposes; they control local State machines and, through them, the delegates who will select a candidate in 1932. If Hoover can persuade the newspaper readers and the commercial interests that he is the right man, he has the renomination in the bag; but if he confuses news interest with public approval and editorials with public opinion, he is due for a discovery that government by head-lines is no substitute for government by hand-shaking, that people are more interested in watching a fight than in cheering a winner, that the Senate delights in nothing so much as to give a strong man the coup de grace, and that the more aloof and scientific he is, the keener will be their appetite for Hoover goulash.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now