Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

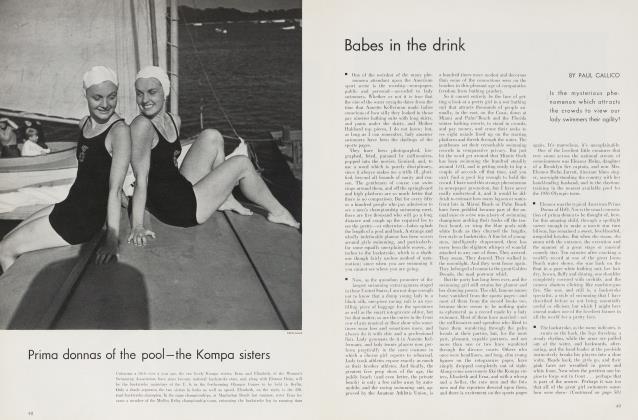

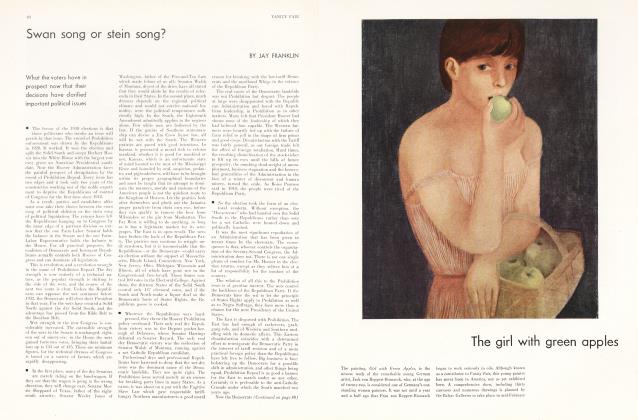

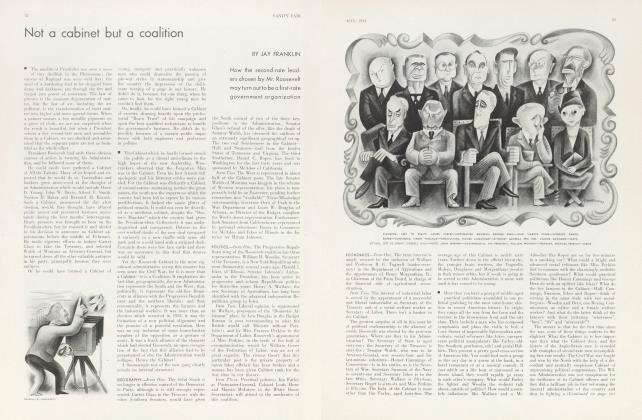

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowFirst, second and third lady—Mrs. Roosevelt

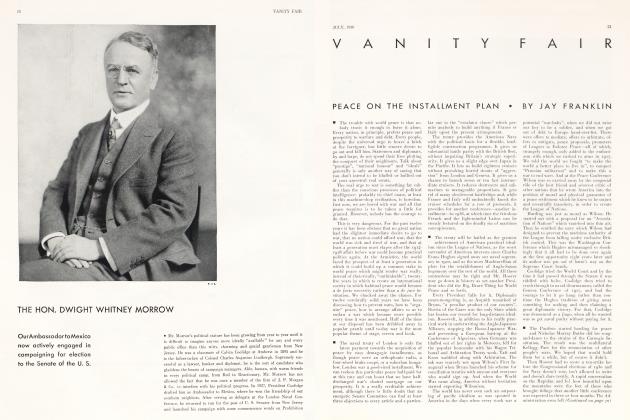

JAY FRANKLIN

No figure in the New Deal has been more widely publicized or more generally misunderstood than Anna Eleanor Roosevelt, wife of Franklin I)., and, by ordinary sporting standards, entitled to recognition as the First, Second and Third Lady of th(' Land.

Dogged by newsreel photographers, sob sisters and caravans of publicists, she is here, there and everywhere. She is on horseback, afoot, in automobiles, trains and airplanes. Today she is addressing a banquet of the wealthy and the powerful, tomorrow she is sympathetically investigating the living conditions of the weak, the forgotten and the very poor. She presides at official dinners, teas and receptions at the White House. She writes a syndicated column in the daily papers. She delivers radio addresses and writes for the glossy-paper weekly publications. She knits, she talks, she travels. She is somebody, the spark-plug of the social conscience in the New Deal; the visible representative of the White House through the length and the breadth of the land.

Mrs. Roosevelt makes such good news and has attracted such a flood of personal publicity that few have stopped to consider that there may he a rationale hack of her activities. Her personality is so vital and attractive, her energy is so phenomenal and she covers so wide an area of human activity that no one seems to suspect that she is a political force in her own right and that she is utilizing her gifts and her position for ends of high social policy in the l nited States.

She is, of course, a member by birth as well as b\ marriage of our premier political famil). A niece of the great "T. R. , she grew up to that sense of social and political responsibility which he had imposed upon the whole clan. V hen she married F. D. R., there was no indication that he was destined to any career other than the gentlemanly practice of law and the administration of a comfortable family fortune. Rut her interests and enthusiasms, admirably reinforcing his ambition, launched him on his political career in the New York Legislature and encouraged him to conquer infantile paralysis.

Mrs. Roosevelt's own political qualifications are considerable and important. She is tremendously thoughtful, and completely natural towards everybody with whom she comes in contact. She is a good "mixer'5, lacking side, condescension or an undue respect for convention, though she never loses her attitude of well-bred dignity. She is a good reporter, a generous giver and has a strong sense of social responsibility. She is, in short, a many-sided person, who gives freely to the life around her and has a genuine and unaffected liking for all sorts and conditions of people.

Her position, as titular First Lady of the l nited Stales, has given her a chance to make the best of these unusual gifts of personality. By definition, the wife of the President is the social leader of her sex in the United States, if she wants to be. She can go anywhere and command a hearing everywhere. She can investigate, analyze and report, free of all those obstacles which impede the activities of mere officials. She is subject to no authority except her own sense of propriety and discretion. Since her husband is immobilized, to a great extent, by the pressure of his official duties, she is his chief point of contact with those people who do not write their Congressmen or break into the headlines.

With these advantages, Mrs. Roosevelt has converted herself from a dynamic personality into political dynamite.

She is reporter-at-large for the White House and is continually disappointed that she cannot nose around coal fields, subsistence homestead projects, city slums and Porto Rican filth without instantaneously accumulating a claque of prominent Democrats, curious onlookers and Girl Scouts. She feels keenly that the President is deskbound and that she is under an obligation to bring him first-hand news of liv ing conditions throughout the country. In addition, she has a direct sense of obligation to assist the under-privileged—a curious mingling of the Late Victorian type of pity with a general belief that something direct can be done quickly to provide them with the belter food, shelter and social attitudes which are the logical result of ceasing to be underprivileged.

But though the symptoms of economic maladjustment distress her, she is, like many of her fellow-countrymen, rather puzzled as to how to deal with the causes which produce them. Like the capitalistic society of which she is a critical hut loyal member, she has no basic plan in her work. Her attention is directed to the miserable conditions in a certain industrial area and she immediately becomes passionately concerned with altering those conditions, but does not fit them into the larger jig-saw pattern of life. She is constantly talking with people who are workers and who knowr the living conditions of the unemployed and of those employed at starvation and substarvation wages. She observes all that she can in the lime when she is free of those ceremonial responsibilities which the First Ladyship owes towards the members of Washington society, where appetites are jaded from too great a choice among abundance, and where ladies are tortured by little fads and fashions. The contrast stimulates her curiosity and impels her to dig deep for the underlying facts which produce this striking irony.

With dogged persistence she reports it all to her husband. V hether or not he wants to listen, he hears. If he is interrupted and doesn't hear all she has to tell him. it is not forgotten, but is taken up at all possible times. This Chinese torture of minorit\ reports has its effects. He ma\ have received contrary information from his own department heads, but he has the small, dramatic drizzle of facts from the person who has made a trip through the drought country and comes hack with tales of forts below zero weather in Dakota homes where there is not one blanket and not one pair of shoes.

I his naturally brings her in close contact with Harry Hopkins and the Federal Relief authorities, whose inconvenient demands for funds spring from know ledge of similar distress throughout the eountrv. and who welcome Mrs. Roosevelt as a means of dramatizing the necessities which the) are required to meet. Mrs. Roosevelt goes to as many places as she can, and has learned not to let advance news of her trips leak out in any way possible.

Nor is this all. Through a warm personal friend, Lorena A. Hickok, she receives much additional information concerning the temper and condition of the country. Miss Hickok, for many years a star reporter on the Minneapolis Tribune and the Associated Press, is a special investigator for the F. F. R. A. In her job, she sits sections of the country, interviews people of all sorts, and makes reports to Harry Hopkins concerning the actual conditions of the citizens who depend on the Government for their livelihood and also on the way the relief organization functions. Miss Hickok is a skilled reporter, a hard worker. She does not have the pigeon-hole social service worker point of view about the wretches who so inconveniently complicate the political and economic machine by not having enough to eat. Mrs. Roosevelt accompanied her on several trips and has heard and read Miss Hickok s reports, although the latter is, of course, in no way responsible to Mrs. Roosevelt. They are friends and allies in the task of dramatizing to the President, through different channels, the social conditions in this most distressful country. Another way in which this is accomplished is hy inviting people to the White House. An expert on the Caribbean makes a trip to Porto Rico. On his return he is immediately and frequently invited to the White House. Mrs. Roosevelt has him seated beside her, plies him with questions, compares his answers with her own observations on her trip to the island.

In addition to all this, literally hundreds of people come to Mrs. Roosevelt, during the course of a month, with reports and complaints. If she is impressed, she adds them to her psychological entourage and surrounds the President with them at meals, as much as she can, and leaves them to talk with him after dinner. Tims she is constantly supplying him with fresh sources of information and later she checks up to sec whether anything has or can he done. While she is most circumspect in not taking undue advantage of her position to go over the heads of the ranking officials in the government departments, this technique has its drawhacks. Certain minor officials, in fields in which she is interested, lake advantage of their knowledge of her interest to adopt an insubordinate attitude towards their own superiors and there is a constant undercurrent of "I'll tell teacher" running through the ranks of several emergency bureaus. As usual, it is the fault of those who are more royalist than the king that this condition exists, but it is only fair to take it into account.

It is also only fair to observe that her judgment of measures is not infallible. The "subsistence homestead" idea, which was tried out in the Interior Department, was one of her special interests. Sound in theory and economically feasible, in actual practice it produced several wasteful and humiliating fiascos before the whole experiment was liquidated by Rex Tugwell's Resettlement Administration, and revised along somewhat sounder lines. But even in this revision, one of the major difficulties was the psychological reluctance of individual officials to deal roughly with institutions in which the First Lady was known to take a w arm interest.

As a matter of fact, Mrs. Roosevelt is too much of a devotee of social service to he a good practical politician. She would like to get results quickly, without paying toll to political practicality. Her interests seem to center around housing and relief projects. She is, in candor, less a peace-maker than a soil of Florence Nightingale. In the economic battlefield, she is more concerned with binding up wounds than preventing conflicts. She makes continual trips to Reedsville, which has become a sort of Federal reservation for standard coal-miners. She recognizes the bundle of mistakes made there hut she also sees families living better and more happily than they have ever lived before, on government bounty—and that fact, in her opinion, justifies even the most avoidable of mistakes. The fundamental problem of supplying them with an economic income instead of a Federal hand-out does not enter into the immediate question of their rescue. Hence the citizens of Reedsville like her. She sits down in their kitchens, talks with them unaffectedly, and has achieved a real personal relationship with many of the families there.

Another problem which she feels keenly is the dilemma of the young people who have come of age during the depression and to whom our economic system, even as modified by New Deal measures, offers little hope of employment or marriage. She realizes the vicious circle of no job, no home, no fixed interests. She constantly listens to plans which w ill help them and persistently checks up on projects which will include more jobs for young people, more social activity, better educational facilities. The National Youth Administration which was set up under the work relief appropriation owes its existence largely to her interest in doing something to reconcile these disinherited children of the depression to the existing order of things in America.

She is also interested in raising the standards of living for domestic servants, realizing that many women who have been employed in industry will never find work there again and that domestic employment will he their only resource. She is interested in projects for giving them training and for improving the conditions under which they will work when they are trained. So far no government help has been provided for such projects and it is unlikely, in view' of our national devotion to the theory of a classless society, that Federal action will be taken to provide the American middle-income groups with a docile servant class.

Her speaking engagements are numerous and somewhat indiscriminate. Being absolutely without self-consciousness and with a great sense of her audience, she is constantly being called upon for everything from "a few words" to a full-dress speech. She nearly always complies and what she has to say is usually well-expressed, intelligent and to the point. She always speaks without notes, frequently ex tempore, and, alone of public figures, never employs a "ghost ' to "whip her ideas into shape". Her magazine and radio work though useful for the dissemination of her ideas— was undertaken chiefly for money. She wanted money to dispense to people and projects in which she had an interest. Recently she lias utilized the charitable intelligence system of the Society of Friends to provide her with advice on worthy causes.

(Continued on page 64)

(Continued from page 38)

I he tremendous fan mail which she receives as a result of this work is. of course, a good political barometer. She gets many letters simply asking for information about various government activities, such as housing projects, loans from the Federal Land Banks, etc., which arc automatically referred to the various government departments for answer.

Mrs. Roosevelt also gets scores of complaints and hundreds of letters giving personal histories. These she reads with interest and tries to do something about each individual case, by writing to someone she knows in the vicinity of the correspondent, referring the ease to a government bureau, or, occasionally, attending to it herself. This mail keeps her in constant and realistic contact with the physical and emotional poverty of the lives of a large section of the American people.

Many—and quite often most cruel have been the wisecracks levelled at her energetic ubiquity, yet she lias become a great practical political asset to her husband. This is not due to any direct effort in that direction. It is because she has a deep realization of the suffering of many people and a warm sympathy for their deprivations that she is able to counteract the dockets, memoranda and statistics which normally tend to anesthetize the social imagination of busy executives.

For a parallel to her activity, intelligence and human sympathy, one must go far hack in history, to the Empress Theodora who, with her husband, the great Justinian, tried patiently and long to restore the Roman Empire. Whether, like Justinian and Theodora, they will fail, is another matter. Certainly the human race reserves its warmest affections for those who deal full-bloodedly with the problems of the day, and attempt to solve them in terms of people as they are, rather than according to intellectual blueprints or philosophic fatalism. Mrs. Roosevelt is keeping the New Deal alive to the fact that our problems are not being solved simply by passing laws and authorizing appropriations. In that she is not only saving the Government from the besetting sin of all political administrations after a few years of office—complacency hut is making it possible for the New Deal to develop into the Next Deal because of, and not in spite of, its own defeated hopes.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now