Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBabes in the drink

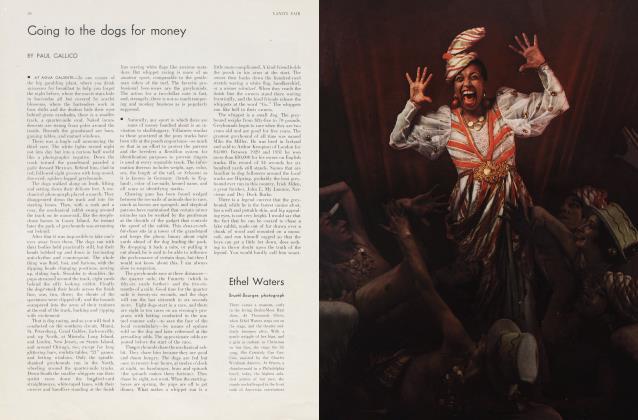

PAUL GALLICO

Is the mysterious phenomenon which attracts the crowds to view our lady swimmers their agility?

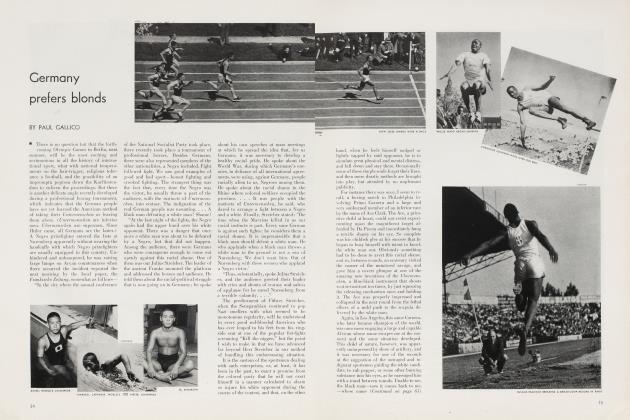

One of the weirdest of the many phenomena attendant upon the American sport scene is the worship—newspaper, public and personal—accorded to lady swimmers. Whether or not it is true that the rise of the water nymphs dates from the time that Annette Kellerman made ladies conscious of how silly they looked in those gay nineties bathing suits with long skirts, and pants under the skirts, and Mother Hubbard top pieces, I do not know; but, as long as I can remember, lady amateur swimmers have been the darlings of the sports pages.

They have been photographed, biographed, feted, pursued by millionaires, popped into the movies, lionized, and, to use a word which is purely disciplinary, since it always makes me a trifle ill, glorified, beyond all bounds of sanity and reason. The gentlemen of course can swim rings around them, and off the springboard and high platform are so much better that there is no comparison. Hut for every fifty or a hundred people who pay admission to see a men's championship swimming meet, there are five thousand who will go a long distance and cough up the required fee to see the pretty—or otherwise—babes splash the length of a pool and back. A strange and wholly indefinable glamor has been woven around girls swimming, and particularly, for some equally unexplainable reason, attaches to the backstroke, which is a rhythmic though fairly useless method of natamotion; since when you are swimming it you cannot see where you are going.

Now, as the quondam promoter of the largest swimming extravaganzas staged in these United States, I am not dope enough not to know that a damp young lady in a black silk, one-piece racing suit is an eyefilling piece of baggage for the spectators as well as the smart rotogravure editor, but for that matter, so are the cuties in the front row of any musical or floor show who sometimes wear less and sometimes more, and always do it with chic and a professional flair. Lady gymnasts do it in Annette Kcllermans, and lady tennis players now perform practically in the same costume in which a chorus girl reports to rehearsal. Lady track athletes expose exactly as much as their brother athletes. And finally, the greatest free peep show of the age, the public beach (and even better, the private beach) is only a few miles away by automobile, and the racing swimming suit, approved by the Amateur Athletic Union, is a hundred times more modest and decorous than some of the concoctions seen on the beaches in this pleasant age of comparative freedom from bathing prudery.

So it cannot entirely be the lure of getting a look at a prettv girl in a wet bathing suit that attracts thousands of people annually, in the east, on the Coast, down at Miami and Palm Beach and the Florida winter bathing resorts, to stand in crowds, and pay money, and crane their necks to see eight naiads lined up on the starting platform and thresh through the water. The gentlemen set their remarkable swimming records in comparative privacy. But just let the word get around that Minnie Ooeh has been swimming the hundred steadily around 1 :04, and is getting ready to lop a couple of seconds off that time, and you can't find a pool big enough to hold the crowd. I have used this strange phenomenon in newspaper promotion, hut 1 have never really understood it, and it would be difficult to estimate how many lagoon or waterfront lots in Miami Beach or Palm Beach have been peddled because part of the annual mise en scene was a bevy of swimming champions arching their backs off the tenfoot board, or icing the blue pools with white froth as they churned the lengths, free style or backstroke. A fine lot of youngsters, intelligently chaperoned, there has never been the slightest whisper of scandal attached to any one of them. They arrived. They swam. They danced. They walked in the moonlight. And they went home again. They belonged of course to the great Golden Decade, the mad post-war whirl.

But the party has long been over, and the swimming girl still retains her glamor and her drawing power. The old, famous names have vanished from the sports pages—and most of them from the record hooks too, because there seems to be nothing quite as ephemeral as a record made by a lady swimmer. Most of them have married—not the millionaires and spenders who liked to have them wandering through the palm fronds at their parties, but, for the most part, pleasant, capable partners, and not more than one or two have wandered through the divorce courts. Others who once were headliners, and long, slim young figures on the rotogravure pages, have simply dropped completely out of sight. Along come newcomers like the Kompa sisters, Elisabeth and Erna, and with a whoop and a holler, the roto men and the foto men and the reporters descend upon them, and there is excitement on the sports pages again. It's marvelous, it's unexplainable.

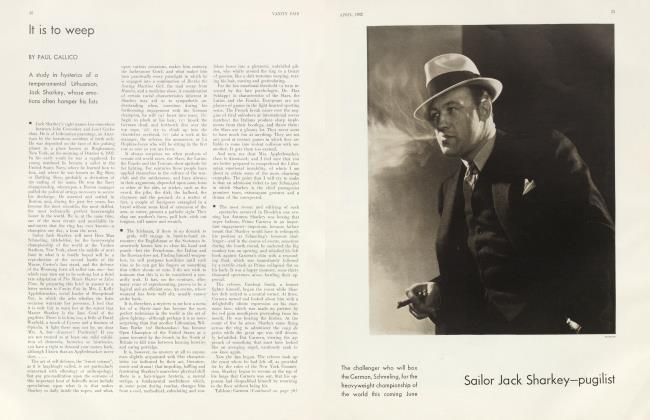

One of the loveliest little creatures that ever swam across the national stream of consciousness was Eleanor Holm, daughter of a Brooklyn fire captain, and now Mrs. Eleanor Holm Jarrelt, itinerant blues singer, one-night-standing the country with her band-leading husband, and in the daytime, training in the nearest available pool for the 1936 Olympic team.

Eleanor was the typical American Prima Donna of 1LO. Nor is the usual connotation of prima donna to he thought of, here, for this amazing child, through a spotlight career enough to make a movie star turn bilious, has remained a sweet, level-headed, unspoiled hoyden. But when she swam. she swam with the entrance, tin* execution and the manner of a great stage or musical comedy star. Ten minutes after cracking a world's record at one of the great Jones Beach water shows, she was back on the float in a pure white bathing suit, her hair dry, brown, fluffy and shining, one shoulder completely covered with orchids, and the camera shutters clicking like machine-gun fire. She was, and still is, a backstroke specialist, a style of swimming that I have described before as not being essentially useful or efficient, but which I might here amend makes one of tin* loveliest frames in all the world for a pretty face.

The backstroke, as the name indicates, is swum on the back, the logs threshing a steady rhythm, while the arms are pulled out of the water, and backwards, alternating, and the band-leader at the poolside instinctively breaks his players into a slow waltz. Heads back, the girls go. and their pink faces are wreathed in green and white foam. Now when the prettiest one begins to forge out in front . . . perhaps that is part of the answer. Perhaps it was too that all of the great girl swimmers somehow were showmen. Eleanor is. She lias all the instincts of a true star and performer that capture the public imagination ability, looks, poise, suitors and an immense joie de vivre. And of all the girl swimmers past and present, she was the only one who developed a capability outside the pool. She has the throaty, husky voice, and curious delivery that enable her to animate and quicken the absurd or soggy lyrics of the modern popular song, and she pleases people far back in the woods who never heard of backstroke swimming.

(Continued on page 58)

(Continued from page 49)

There were, to be sure, some who took flyers at the movies. Helene Madison, a magnificent figure of Briinneli i I de, and a great swimming champion in her day—which was just before and during the 1932 Olympic Games in California tried pictures and it didn't work. Her predecessor as champion, Josephine McKim, the darling of Panama and Honolulu, vanished in Hollywood, after doubling in a few pictures.

Now the moving pictures, whatever one may know or say of them, are reasonably quick to appreciate what appeals to the public, and the very fact that so many lady swimmers got a chance in Hollywood bears out the curious appeal they seem to have. After the 1932 Olympics, Eleanor Holm was signed by a studio, and sent to school for six months to learn how to he a screen actress, because Eleanor was smart enough not to capitalize on her swimming, as she wished to remain an amateur. The studio didn't have sufficient patience, or Eleanor wasn't a good actress. But the pool or beach sells out whenever she swims, or for that matter, whenever any of them swim.

They must be champions. They must break records. This seems to be an essential part of the scheme. The two handsome and twin-like Kompa sisters have been swimming at the Women's Swimming Association pool, and in local meets for years without attracting any undue attention. And they were just as pretty then as they are now. But when one sister won the backstroke swim in the National championships, and the other put her team out in front in the national medley relay championship in the same meet it was a riot. Splash went lh(' two sisters into the national spotlight. Here was not one, hut TWO pretty faces wreathed in foam. Last summer, at the Jones Beach Water Circus, the two girls swam an exhibition together, heat for beat, stroke for stroke, side by side, and the hand played a dreamy wait/, and. by George! it WAS pretty. And the crowd of thirty-odd thousand, or all that could squeeze to a view, my friends, just went nuts.

It is a curious thing about girl swimmers and divers that they do not necessarily have to lx* what Hollywood or the fan magazines call "Glamour Girls" in the picturesque, or starry-eyed, sense. Two of the greatest water drawing cards of today are Katherine Rawls, a slim, boyish-looking child, perhaps the greatest allround water woman the world has ever known, and the greatest free style middle distance swimmer of today, I.enore Right recently married —a charming, sweet-faced girl who is as shy and retiring as one could wish. Both she and Katherine Rawls draw tremendous crowds wherever they appear.

I realize that this thesis has not advanced very far in explaining the attraction of the water ladies, but doggone it, they all had something. In the boom days there were Aileen Riggen, and Sybyl Bauer, and Helen Wainwright, Doris O'.Mara, and Lisa Lindstrom, Agnes Geraghty, Kit Brown and Helen Meanythe divers, and the marvelous Gertrude Ederle, who, in addition to swimming the English Channel, turned into one of the finest of human beings, hut I do not know that this is necessary.

Perhaps none of those names means anything to you. The whole business may lie only in the imagination of a fastidious commentator who doesn't like hippy or muscly lady athletes, and none of the swimmers is that, because swimming is practically the only sport that develops long, flat, graceful muscles.

As I look back over years of watching the ladies swim and dive, 1 realize that I am indebted to many of them lor moments of spectator-excitement, and moments of sheer beauty. There is a moment in the swan dive of Mrs. Dorothy Hill, the former Dorothy Poynton of Los Angeles, Olympic high platform champion, when she becomes a white gull, motionless a-wing, before a swoop into the sea. There was, in those same Olympics, Mrs. Roof Gilson, then Georgie Coleman, a creature all tan and gold and magnificent vitality as she took off from the ten-foot board. She had a mop of curly yellow hair and never wore a bathing cap, and it used to please me tremendously to hi' there to watch her dive when it was still dry, and then to see her first emergence from the water with a shake of her head like a puppy's that sent the water flying and left her as sleek as a brown seal. Mrs. Hill is still high-platform champion, although, bless us, the national springboard champion is a little frog by the name of Mary Hoerger, age twelve.

For thrill, I will never forget the finish of the Olympic 400-Meter Free Style swim in which Helene Madison barely touched out I.enore Kight by a split fraction of a second after as plucky and tenacious a battle as you will ever see, with Miss Kight gaining on Miss Madison down the stretches, and losing it back again on the turns, due to the Seattle girl's greater size and power on the push-off. Neck and neck, all the way.

There is another sweet duel in the offing. The Kompa sisters, national backstroke champions, have come along with a sudden rush. They have stolen the spotlight from the little trouping swimming star who is out hack country somewhere with her husband and his band, singing—-"Every Little Doggie HAS his day;" but Eleanor Holm will return to challenge the Kompa girls for the right to swim on another Olympic team, and the photographers will simply turn themselves inside out for that one.

Well, they start as child prodigies, and grow up and become champions, and become famous, and then they marry and vanish, and new ones come up and THEY get photographed and written about. Do you suppose it is because all other lady athletes are pretty ungainly and have piano legs, or truck driver shoulders, or Grand Rapids ankles, and the girl swimmers all seem to be comely, and have lovely figures? Perhaps, though, most lady swimmers seem as a rule to have big feet and— oh, the hell with it. I like 'em. Maybe you do too.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now