Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMurders in the belfry

EDMUND PEARSON

George King, late one afternoon, was reflectively playing the piano. He sat in the Sunday-School rooms of Emanuel Baptist Church—a pretentious wooden building with a tall spire. It stood on a San Francisco street, a street of jig-saw and gimcrack houses.

George was a wide-eyed and blameless lad of nineteen: organist of the Church in which he was now making melody. He had dropped into these empty and dismal halls, on a chilly Wednesday afternoon, apparently to limber up his fingers and console himself with music, lie could hardly have been rehearsing for the evening service of prayer, for the tune he played was secular. It fell pleasantly on his cars—some composition popular at this date (April, 1895), when persons who sal down at pianos were apt to execute Narcissus, by Ethelbert Nevin.

So far as George King knew, he was alone, and the notes of the piano reached every corner of the Church. They may have been audible even in the belfry, from which one could view the bay and the hills. And while George's harmless tinklings went on, there was going forward, in the belfry, San Francisco's great sadistic murder: the first of a brace of crimes which within the course of little over a week were to shock and mystify the entire Pacific coast.

It occurs to me that young Mr. King may deserve the title of Innocent Bystander Number One, of all the world. For, as he played, unaware that he was furnishing musical accompaniment, events of an unspeakable nature were taking place within a few feet of him. They were to cause the eloquent barristers of California to cite Nero and Caligula, Gilles de Retz and the Marquis de Sade, to explain such horrors. And this in days when people did not bandy these names about; when the hideous abnormality to which de Sade gave his name had not been cheapened, by literary folk, into a trivial catch-word.

After a while, the music was interrupted. Some noise caused King to look behind him. A pair of folding doors opened and there came into tin' Sunday-School rooms not Nero nor Caligula, not even the Marc'chal de Retz, nor Jack the Ripper. Things were queerer than that, for the gentlemanly young murderer who came in was the Assistant Superintendent of the SundaySchool, and his name was William Henry Theodore Durrant.

His face was pale and his hair dishevelled. King, recognizing a friend and fellowlaborer in this Vineyard of the Lord, remarked that Mr. Durrant looked a hit washed-out. The other replied: "So would you, if you had been through what I have been through.

He explained that he was almost overcome by gas. There was a bad leak of illuminating gas, and, zealous for the welfare of the Church, he had been engaged upstairs in a struggle with pipes and burners. George King may easily have been surprised at the looks of his dapper friend, for Mr. Durrant, in addition to his SundaySchool duties, acted as usher in the Church, and (clad in frock coat, with a rose-bud in the button-hole) spent Sunday mornings ceremoniously escorting ladies into their proper pews.

Now, he sat down, and faintly proffering George a half-dollar, asked for a bottle of Bromo-Seltzer, and quickly. As Mr. Durrant, when not engaged in sacred affairs was a student at Cooper Medical College, he knew what he wanted. George King dashed out to the nearest pharmacy and came back with the blue phial. Durrant restored his queasy stomach with a draught, and after a while the two friends closed the Church—each had a key—and went their ways.

Both returned that evening for the prayer-meeting. Mr. Durrant sought out a lady named Mrs. Tryphena Noble, and asked the first of his hypocritical questions.

"Isn't Blanche coming to the prayermeeting?"

Mrs. Noble muttered that she thought not.

"That's too bad," he replied. "I rode downtown with her this morning—on her way to school, you know—and I promised to bring her The Newcomes. But I have forgotten it. Will you please tell her I'll bring it to Church, Sunday ?"

Durrant was in no doubt why Blanche Lamont, Mrs. Noble's niece, had not come that evening. But Mrs. Noble and her family were much disturbed, because Blanche had not returned from school. They had disagreed over the question of alarming everyone at the Church with the news of the mysterious absence. In a day or two, the disappearance could no longer he kept secret: the police had to be consulted, the reporters arrived, and within the week, through head-lines and newspaper portraits, the name and face of Blanche Lamont became familiar to everyone in San Francisco. She was a native ol Illinois, twenty-one years old, and had been living in the city about six months.

Officers and members of Emanuel Church called on the girl's uncle and aunt, to offer suggestions and sympathy. Mr. Durrant came, and was polite and solicitous; he had sometimes accompanied Blanche to school, but, more often, brought her home from Church or from the Christian Endeavor meetings. To the family, and to fellow-students, Mr. Durrant said that Blanche was a very innocent young lady; he feared that she might have been trapped in some house of ill-fame. He understood that there were, in San Francisco, places of this kind, frequented by wicked people.

In his quiet way, he kept up his interest in the absent Miss Lamont. In the following week came Good Friday, and on that day the janitor of Emanuel Church happened to be at Market Street Ferry. He encountered Mr. Durrant, who explained that he had a lip: somebody told him that Blanche Lamont might be crossing the Bay, and he was therefore hoping to see her. He did not add that his ride with her on the street car, the morning of the day she vanished, seemed to be her last public appearance with any gentleman, and caused his friends to ask facetious but annoying questions about "that girl you ran away with."

The same afternoon, Mrs. Noble received a package by mail. In it were two or three cheap little rings, the property of Blanche. On the wrapper, some one had thoughtfully written the names of Professor Schernstein (Blanche's music-teacher) and of George King.

The morrow, Saturday, was the tenth day since the disappearance. The Ladies' Aid Society betook themselves to Emanuel Church to put up Easter decorations. As they moved about, with their bunting and their lilies, one of them chanced to open the door of a small room near the Sunday-School library. The walls were splashed with blood, and on the floor lay the huddled body of a young girl.

The crimes of rape and murder had been committed. She had been choked to death, and there were seven knife wounds, some of which would have been fatal by themselves. The arteries in the wrists were severed.

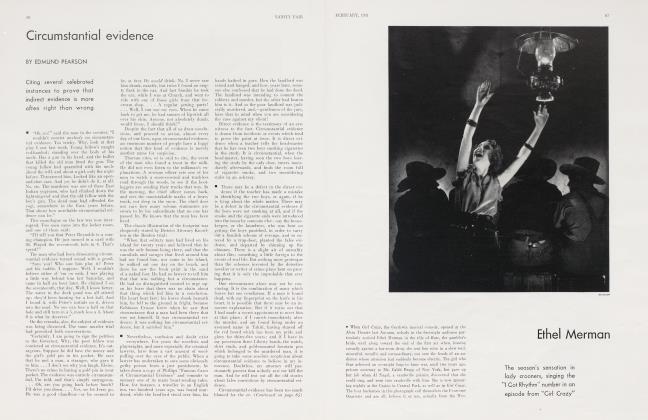

A reader of this article may understand why the Church people, the police and the reporters experienced a shock and a surprise when it was discovered that this was not the missing girl whose name and portrait, for the past week, had been on the front page of so many papers. Instead, Whom Are You Celling At, Eh? carolled Beatrice Gladys Lillie when, at the age of fourteen, she was known to nearly every concert-hall goer in Canada as a "character costume vocalist and impersonator". Other songs in her surprisingly extensive repertoire were My Pretty Kickapoo, Nicoleenie, and The Strawberry Girl. Two years later, in London, Andre Chariot heard her burlesquing a serious arietta and signed her up on the spot. Since then, Miss Lillie has soared, like a lark, into the dizziest heights of popularity, both here and abroad. Her main interests at present are (1) starring in the W inter Garden success, At Home Abroad, from which these four photographs were taken; (2) singing in the night club Montmartre; (3) Harrow-on-the-Hill, where her son, Sir Robert Peel, is at school it was someone who had not been missed at all, a slight, little curly-haired damsel named Minnie Williams. A Canadian by birth, she had been working, in various humble callings, in San Francisco, and depending for her pleasures on the parties and entertainments of Emanuel Church, of which she was a dutiful member.

She was moving her lodgings, the day before, from Alameda to San Francisco, and intended to cross by ferry in the afternoon at about the hour, by the way, when Mr. Durrant fell impelled to watch the ferries to follow up his clew as to Blanche Lamont. Miss Williams reached her new lodgings, and departed in the evening for a Christian Endeavor "sociable", at a private house. But at this place, she never arrived.

The police now descended upon Emanuel Church, and, to the distress of pastor and people, suggested that no Easter services be held there. Instead, they began a thorough search. The hunt Avas kept up until midnight, when every part of the building had been examined except the belfry. The door thither was locked and its handle broken.

Coming back early Easier morning, police broke down this door, and went to the top landing of the belfry. Here, in the dim light, they found the naked body of Blanche Lamont. She was lying with her feet close together, her hands folded across her breast, as if prepared for burial. She had been strangled. Two small blocks Avere placed to hold her head in position: they were like the blocks used for similar purposes in a medical college. Her clothes were stuffed into rafters or under boards.

Officers decided that they Avished to.question Mr. Durrant. They discovered that he had been seen with Miss Lamont much later in the day of her vanishing than he had admitted. It proved necessary to follow him to a place called Mount Diablo, Avhere he had gone as a member of the State Signal Corps. He Avas not a Native Son,*but a Canadian, born in Toronto. In a number of legal and highly proper ways, he Avas an active man. His secret diversions, with girls, Avere what provoked the curiosity of the police.

Durrant was voluble Avith explanations, but the evidence made a Grand Jury indict him for both murders. The astounding nature of the case Avas that, if the charges were true, lie had, on some pretext, persuaded Blanche Lamont to accompany him to the Church, boldly risking discovery in broad daylight. Nearly interrupted at this time, by George King; kiunving that still other people had keys to the Church, and that San Francisco was excited by the disappearance of Miss Lamont, he had returned. nine days later, to the scene of the killing, and in the empty Church on Good Friday night, struck again—his victim, this time, being Miss Williams.

His trial for the murder of Blanche Lamont lasted from July to November, and later legal proceedings kept the case open for nearly three years from the dale of the murders. Rather surprisingly, the Durrants, people in modest circumstances, AN ere able to engage a trio of San Francisco's ablest lawyers, who fought the case with utmost persistence. Durrant never had to explain, in Court, his actions on Good Friday, but he gave, on the Avitness stand, a detailed account of every moment of the day Avhen Miss Lamont vanished.

He sought to establish an alibi. The time of the murder being fixed as between 4:20 and 5 P.M., he asserted that from 3:30 to 4:15 he Avas in the Medical School, listening to a lecture on "Infant Feeding by one Dr. Cheney. A roll-call was taken at the end of the lecture, and its result entered in a book. I nluckily for Durrant, neither the lecturer nor any student could testify to his presence, and if someone else had answered to his name (according to a frequent custom at the school I that person was UOAV discreetly silent. The record of attendance was produced, so blurred, that if it did not actually suggest to the jury a suspicion that it had been tampered Avith, it did nothing to help Durrant.

The State traced Durrant and Miss Lamont through the city, on and off streetcars, and to the door of the Church. This was done by a series of AN it nesses, seven in all. both men and Avomen. The defence tried to show that this witness Avas too old, this one too young, that one deluded and another one corrupt. Perhaps the jury might have been shaken, if a pawn-broker had not testified that Durrant tried to paAvn one of Blanche Lament's rings. The prisoner gave a painfully minute description of his altruistic endeavors to mend the gas-pipes— his real reason, he said, for coming to the Church that day. But the evidence of the janitor, and of the Church trustees, tended to prove that this story Avas a long and laborious lie. His amateur plumbing, even had it been performed, was unnecessary. It was clear that George King was present in the Church, strumming on the piano, during at least part of the hideous rites in the belfry.

fhe name of Minnie Williams could not be mentioned to the jury, since Durrant was not tried on that charge. Had it been permissible, Avitnesses would have shown that Durrant and Miss Williams were seen together near the Church, if not entering it, at eight o'clock on Good Friday night. And that Durrant arrived alone at the Christian Endeavor "sociable", at 9:30—his rather long hair disordered, his forehead wet with sweat, and his hands so soiled that he had to retire and wash them. Having done that, and having suitably arranged his hair, he joined in the mild festivities of the evening. It is said that Minnie \\ illiams's purse was found in his overcoat pocket.

(Continued on page 64)

(Continued from page 24)

The evidence as to both murders was wholly circumstantial. And all advantage was taken of this hv people who believe that criminals should he I set free unless they have obligingly taken witnesses with them to watch the commission of the crime. Durrant. in his own testimony, was evidently more glib than sincere: the jury, after only twenty minutes' deliberation, convicted him of murder in the first degree.

Every possible delay, every writ and appeal to higher courts, including the Supreme Court of the United States, having been employed, Durrant, on January 7, 1898. stood on the gallows at San Quentin. Many of the newspapermen must have realized that they had committed all the sins against good taste in reporting this murder, hut they had no doubt of Durrant's guilt, since they had reason to believe that, in private, he had confessed. So they were probably unmoved when the dying man, in a final recitation, nobly forgave "the Press of San Fran-

"It is they," said he, while the hangman waited, "who have forever blackened the fair name of California by putting to death this innocent hoy."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now