Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

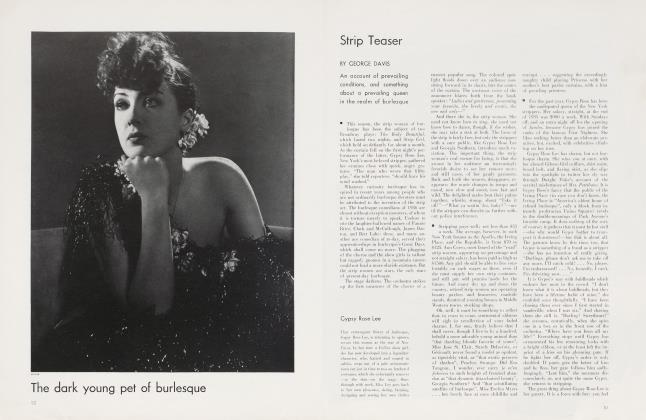

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe dancer and the queen

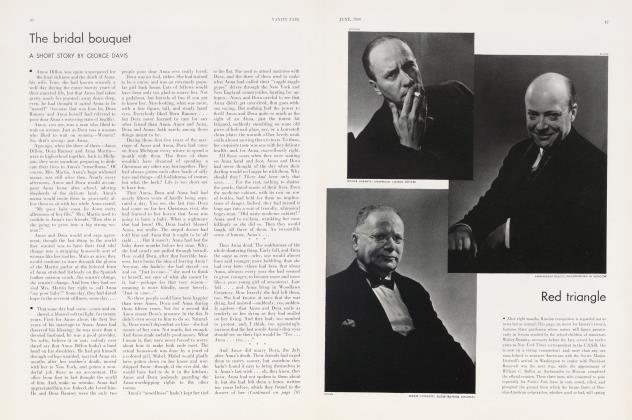

GEORGE DAVIS

The story of the friendship of Roumania's Marie for Loie Fuller, who danced and campaigned to a Queen's taste

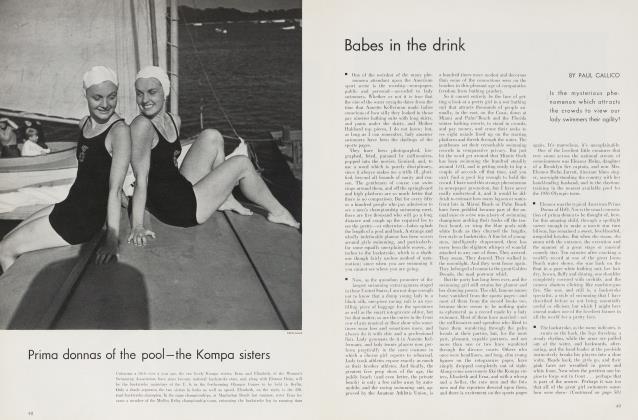

Thirty years ago, there was no dancer so breathlessly watched, in Europe and America, as Loie Fuller. She was born in Chicago, and, at the age of two and a half wars, set forth on a career of recitals, lectures. Shakespearean readings, and melodramatic play-acting which took her to three continents, but brought her little acclaim until, in 1891, she introduced her famous Serpentine Dance to a quicklyravished public. It was the first flutter in that Edwardian whirl of veil dances, which trailed on and on, past Edward, until both Loie Fuller and her pupil, Isadora Duncan, died in the late 1920's. The Serpentine Dance was a wafty thing of chiffon scarves and colored lights, and for twenty years it cast its spell upon the rapt audiences of New York, London, and Paris.

Those who saw Loie Fuller have not forgotten the Serpentine Dance. To many, however, another part of this famous dancer's life is hardly known. This was her long and deep friendship for Marie, the Queen Mother of Roumania. These two women—the dancer and the Queen—met for the first time under very curious circumstances. Rumor has never wholly accounted for their friendship, and rumor does not answer for its abrupt ending.

. . Some have wondered at the friendship of a queen for a woman whom some would call lowly. That woman is Loie Fuller. Her name often has been slighted. That woman stood by me when my back was to the wall. That woman gave me her life, in my hour of need. She went all over America seeking aid for my people. This has been forgotten by the rest of you, but I no longer could be silent. . . ."

Ihus warmly, loyally, spoke Marie, Queen of Roumania, in Maryhill House belter known to the natives of Klickitat County, Washington, as "Sam Hill's Folly" on the afternoon of November 3, 1926. The occasion? Well, it seems to have been thought of—at least spoken of. written of as a "memorable" one; at the time, that is. Doubtless Klickitat County remembers it vividly even now: after all, a Queen does not come that wooded way often. And here she was, in glamorous flesh and blood, having crossed a continent, an ocean, another continent, just for this purpose—to dedicate this grim concrete and steel monstrosity which for twelve years had loomed darkly above the Columbia River. Maybe Sam Hill wasn't a great man (but what mightier name, in the Northwest, than that of Jim Hill, railroad builder and Sam's father-in-law?) ; and if Sam hadn't got the King and Queen of the Belgians out to dedicate his museum, his Folly, why, that was because a war kept them away; anyway, better late than never: here, twelve years later, was Marie, Queen of Roumania, and wasn't she something worth waiting for!

". . . and as woman to woman, I wish that there would be no doubt in my heart that that woman gave me hers. . . ."

Was not the Queen's wish a command? Respectfully the crowd applauded. The Queen went on to speak once more of her love for her own country and her love for America. . . . That same afternoon, in the royal train, Loie Fuller, who had not been present at the dedication ceremonies, wept when told the Queen's tribute. One week later, in Denver, Loie Fuller, accompanied hv her press agent and her secretary, left the royal train and journeyed back alone to New York. She had not seen her friend, the Queen, since Maryhill. The newspapers reported that the exits from Loie's car toward the Queen's apartments had been barred, to prevent her calling on Her Majesty, who was said to be exhausted almost to the point of a nervous breakdown by intrigues in the royal party. Her Majesty, it was claimed, had been put in the position of agreeing to the dismissal of her friend for "the good of the party".

Hie Queen and the dancer were never to meet again. Intrigue, envy, had done their wicked work. Marie's visit to the United States, inauspiciously begun, despite best official efforts, ended under a cloud. It was rumored that Ferdinand, her husband, had ordered her home. What the arrival of Kuggles did to Red Gap, the arrival of the Queen apparently had done to the whole l nited States. A cynically amused world was kept informed of every squabble in the royal party. So the Queen sailed back to Europe November 21, not December 11, as originally planned. A short time later, Loie Fuller sailed—but her destination was Paris, not Bucharest. Probably she hoped that in more serene times she and her friend, the Queen, would meet again, but that was not to be. She died at her home in Neuillysur-Seine in the late fall of 1927. Her death attracted comparatively little attention— the world was still thrilling to the spectacularly tragic death of another American dancer who had long ago been Loie's protegee: Isadora Duncan.

Now that Marie has, or seems to have, more time on her still lovely hands, and has taken seriously to literature, it may be that she will some day add to those gracious few words uttered in tribute to her friend in far-off Maryhill. As yet, she has not; neither in My Life, nor in the recent Ordeal. Her Majesty's account of her (and Roumania's) sufferings during the World War. It does seem a pity that the Queen did not save this last title for the saga of her American tour!

But even should the dowager Queen of Roumania, seated at her writing table in Cotroconi Palace, decide to put down a more enduring record of her affection for poor vanished Loie, it is doubtful if many of her readers will recall much of the world-wide fame once enjoyed by the dancer. For some reason, Loie's legend, unlike Isadora's, has not glowed brighter with time; its light, indeed, is dim. Yet her contribution to the dance, and the theatre, was far from a negligible one; and her life of nearly sixty years was crowded and colorful.

Born in Fullersberg, just outside Chicago, Loie made her debut at the age of two-and-a-half years, when, acting on impulse, she got up in the Chicago Progressive Lyceum and made an impromptu address. She sang and played the piano at the age of five, and at six was giving readings of Shakespeare. When only thirteen, she became a professional temperance lecturer, introducing the "horrible example" method of appeal. Wherever she went, it is said, she would find the town drunkard and exhibit him on the stage that night as a warning to all erring topers.

Still in her teens, Loie went barnstorming all over America in Shakespearean plays. A few years later found her playing opposite Nat Goodwin in the old burlesque, Little Jack Sheppard. In spite of her success in burlesque (which bore no resemblance to the present-day Minsky's) she developed a distaste for it and turned back to the drama, appearing in Rider Haggard's She, under the management of Charles Frohman. Followed a long South American tour, financially disastrous, and unsuccessful ventures in London and New York. Then, in 1891, in a play called Quack, M.D., Loie introduced her sensational Serpentine Dance,and international famewashersat last.

". . . Not even the most realistic description, or the most earnest study of the illustrations which still exist of the girl-dancers of Herculaneum and Pompeii who, in mistlike robes, with ungirdled waists and sandaled feet, with languorous movements and rapturous uplifted faces, entranced even the most besotted among the revelers at the notorious bacchanalian orgies of those cities of the past . . . can convey any idea of La Loie's exquisite dancing," declared an English home magazine of the '90's. The writer ended by saying, however, that "there is no discordant note in her whole performance, or a gesture or movement which would wound the susceptibilities of the most modest-minded of British matrons or maidens."

(Continued on page 61)

(Continued from page 54)

And in her private life, the dancer was a model, as they say, of decorum.

Once more the English home magazine: "The dancer, in private, is a bonnie, blue-eyed little woman, plain in her dress, and with a sweet frankness of manner and speech which renders her eminently attractive ... a good woman, against whose reputation a censorious and jealous world has never dared to breathe a word." True, Loie had once had sent to Sing Sing prison a certain Colonel William Hayes, with whom she had contracted a common-law marriage, only to discover that he already had one living wife; but either the event received scant publicity, or tinpublic, in its infinite wisdom, decided that no onus attached itself thereby to their favorite.

Nor would Paris, where, for many years, La Loie was the most brilliant star of the Folies-Rergere, hear evil of her. Said the Revue lllustree: "Wicked tongues—they exist even in the world of the dance—have spread wicked rumors about La Loie, saying that her love of the Greek dances permits her to justify the morals of antique times. ... To those who know Miss Fuller, things are as clear as the light in her dances, limpid as the rays of her electricity, the blue of her childlike eyes. She belongs to her art, to her dream of happy humanity. . . ."

Like Isadora, Loie Fuller enjoyed the friendship of many of the great writers and artists of her day. Catulle Mendes, Jean Lorraine, and Henry Baer dedicated poems to her. Anatole France was one of her ecstatic admirers. For many years she worked with Vuguste Rodin, and she made an effort to establish a Rodin Memorial Institute in the United States—an effort finally resulting in the Legion of Honor Palace at San Francisco.

It is perhaps difficult for modern students of the dance to understand what the late '90's and the early 1900's found significant in the spectacle of a lone woman manipulating scarves under the play of multi-colored lights. W e must keep in mind that stage lighting was then in a comparatively primitive state, and there can be no doubt that in the field Loie Fuller had a profound influerfee. Too, the invention of illuminated dancing by La Loie coincided with the era of Impressionism in painting. The same plays of light, the same spots of color, which absorbed the Impressionists were reproduced on the stage by her.

"Any self-respecting bird would weep with chagrin at seeing Loie Fuller spread the wonderful wings of her drapery and go sailing through the shafts of light that are aimed at her by faithful calciums. She is a spectacle

that is scarcely equalled by rainbows, torchlight, processions. Niagara Falls, or naval parades. . . ."

Yes, the Loie Fuller of the ornate '90's and the still more ornate 1900's had traveled far from the child temperance lecturer of Fullersbcrg.

It is certain that, among all the friends and admirers which her art and her vital personality had won for her, there was none whom Loie cherished quite as fervently as Her Majesty, Queen Marie of Roumania. Visitors to Loie's villa in Neuilly-sur-Seine never failed to hear the plump, ageing little lady of the flowing robes and the dark glasses (her beloved title, The Fairy of Light, had cost her dear* speak fondly of her royal friend.

They had met a few years before the War. The story is that Loie, after a concert in Bucharest, found herself unable to cash the check which was her artist's fee, the banks being closed for a holiday. In despair—she did not have even train fare to the city where she was next scheduled to appear— Loie conceived the mad idea of applying for aid to the royal palace. And it worked! It more than worked: the Queen herself wished to speak to the American dancer, to express deep admiration of her exquisite art. So the two distinguished women met; and when La Loie at last left the palace, she was Her Majesty's friend.

"That woman stood by me when my back was to the wall. That woman gave, me her life in my hour of need. . . ." During the War, Loie and her troupe of girl dancers toured in Europe and America, raising money for the Allies and, more especially, Roumania. And Roumania and Queen Marie were grateful. Not only was Loie decorated for her services, but, just after the War, Clare Sheridan, visiting Queen Marie at the summer palace at Sanaia, discovered Loie staying there as an honored guest.

A shame, that the long friendship of the Roumanian Queen and the American dancer had to come to such an unhappy, grotesque end!

Loie's unpublicized arrival in America a few weeks in advance of the Queen. The hiring of detectives—by whom, nobody is quite sure—to shadow Loie's every public move. The threatened resignation of M. Djuvara, Roumanian Charge d" Affaires at Washington: "I refuse to serve under a dancer." Djuvara is said to have complained that Miss Fuller, as a close personal friend of the Queen, was attempting to give him orders contrary to those received from Roumania. Who can say . . . ?

Then, after the arrival of the Queen —in a drizzling rain, with little cheering, it was announced by the "Mothers' Memorial Foundation" that Miss Loie Fuller was to have charge of the spectacular dances to be presented for the Queen's entertainment at the Metropolitan Opera and at the Sesqui-Centennial in Philadelphia. Investigation showed that the M. M. F. was only a subsidiary of the "Woman's Universal Alliance", founded to "establish an acropolis to womanhood in all lands'. Congress had been asked to appropriate SI.000.000 for that purpose, but (Continued on page 62) the appropriation had been pigeonholed. A lady named Mrs. C. Crittenden Calhoun, of Washington, D.C., appeared to he head of both the M. M. M. and the W. U. ?\.; unkind rumor had it that Mrs. Calhoun had been able to purchase a magnificent estate near Washington, where she entertained extensively, but that Womanhood had as yet to benefit in anyway; Womanhood, that is, with the capital W.

(Continued from page 61)

The Sesqui-Centennial recital took place October 22, and was hardly a signal success. I he Queen's box, with its huge letter M in electric lights, had been built facing the audience, with its back to the stage; there was no public reception for box holders afterward—the attendance failed to justify a Queen's reception. The Metropolitan Opera recital (both of a ballet signed by Her Majesty herself, The Lily of Life) was a rather dreadful fiasco. $5.50 seats were sold in the street, the night of the performance, for $.50; a publicity man attached part of the ticket sale; and Mayor Walker refused to attend, and Governor Smith, and the Whitneys, and the Vanderbilts. It was unfortunate, the whole affair. And Womanhood still has no acropolis.

The Queen left for Washington, for Maryhill, where she had promised to dedicate Sam Hill's museum; Mr. Hill was reputed to have once been given an old sceptre by the Queen's husband, King Ferdinand. In Denver, the Queen received a messenger from the Kokomo W.C.T.U., begging her to deny that she occasionally indulged in an afterdinner cigarette. Major Stanley Washburn, special aid to Her Majesty, failed to "get on" with Mr. Hill. Colonel Carroll, the Queen's across-country host, was obliged to request Mr. J. A. Ayers, a Ford representative for Lincoln cars, to quit the royal train— not before Mr. Ayers was quoted as saying that Mr. Ford had defrayed expenses of the Queen to the tune of $500,000, and that he (Ayers) had himself been loaning money right and left to members of the royal party.

Poor Loie Fuller should never have taken it into her head to join that wrangling party; but she did, in Spokane, and was immediately drawn into the quarrel. And at Denver, "for the good of the party", she said good-bye to the Queen, her friend, by letter, and proceeded on alone to New York.

. . . Vanished those simple, pre-War days when one cashed a check by applying to the royal palace in Bucharest! Poor Loie!

"You are one eternal sacrifice," said the dowager Queen recently, to a correspondent of the New York Times, her thoughts drifting back over the years when she was a reigning sovereign. "Your friends are torn away from you, through jealousy or circumstance. . . ." Among other troubled days, was Marie recalling several in our own American West? '7hit," concluded Her Majesty calmly, '7 have a good conscience, and peace of mind is a marvellous thing."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now