Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowIt is to weep

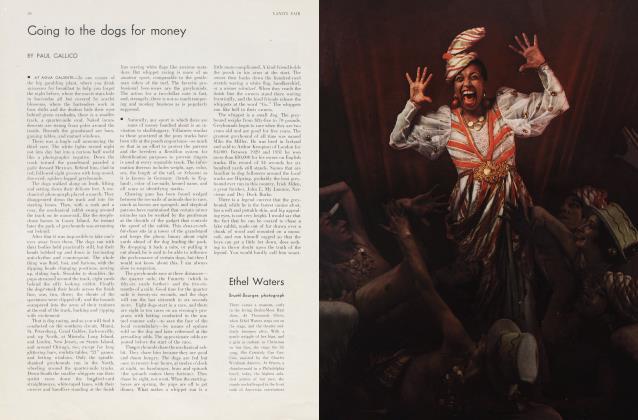

PAUL GALLICO

A study in hysterics of a temperamental Lithuanian, Jack Sharkey, whose emotions often hamper his fists

* Jack Sharkey's right names lies somewhere between John Coccoskey and Josef Cuckoshay. He is of Lithuanian parentage, an American by the fortuitous accident of birth only. He was deposited on the face of this pulsing planet in a place known as Binghamton, New York, on the morning of October 6, 1902. In his early youth he was a vagabond. In young manhood he became a sailor in the United States Navy, where he learned how to box, and where he was known as Big Skee, or Battling Skee, probably a derivation of the ending of his name. He won the Navy championship, whereupon a Boston manager pulled the political strings necessary to secure his discharge. He married and settled in Boston, and, during the past five years, has become the most scientific, the most skilled, the most technically perfect heavyweight boxer in the werld. He is, at the same time, one of the most erratic and unreliable inand-outers that the ring has ever known—a champion one day, a bum the next.

Sailor Jack Sharkey will meet Herr Max Schmeling, titleholder, for the heavyweight championship of the world at the Yankee Stadium, New York, about the middle of next June in what it is fondly hoped will be a reproduction of the second battle of the Marne, Custer's last stand, and the defense of the Woosung forts all rolled into one—but which may turn out to be nothing but a third rate adaptation of The Music Master or Lilac Time. In preparing this brief in answer to a letter written to Vanity Fair by Mrs. J. Kelly Applethwacker, social leader of Sheepshead Bay, in which she asks whether the fistic occasion warrants her presence, I feel that it is only fair to warn her at the outset that Master Sharkey is the Jane Cowl of the pugilists. There is in him, too, a little of David Warfield, a touch of Cyrano and a tincture of Ophelia. A fight there may not be, my dear Mrs. A, but—draymer? Positively! If you are not treated to at least one mild exhibition of dementia, hysterics or histrionics, you have a right to demand your money back, although I know that an Applethwacker never does. . . .

The art of self-defense, the "sweet science", as it is laughingly called, is not particularly concerned with ethnology or anthropology; but any pre-meditation upon the outcome of this important bout of fisticuffs must include speculations upon what it is that makes Sharkey so daffy inside the ropes; and what, upon various occasions, makes him outweep the lachrymose Cowl; and what makes him turn practically every prizefight in which he is engaged into a combination of Bertha the Sewing Machine Girl, the mad scene from Hamlet, and a medicine show. A consideration of certain racial characteristics inherent in Sharkey may aid us to sympathetic understanding when, sometime during his forthcoming engagement with the German champion, he will (a) burst into tears, (b) begin to pluck at his hair, (c) knock the German dead, and forthwith dive over the top rope, (d) try to climb up into the chandelier overhead, (e) take a sock at his manager, the referee, the announcer, or La Hopkins-Joyce who will be sitting in the first row as sure as you are born.

It always surprises me when products of certain old world races, the Slavs, the Latins, the Franks and the Teutons, show aptitude for fist fighting. For centuries these people have applied themselves to the culture of the warclub and the snickersnee, and have always, in their arguments, depended upon some form or other of the shiv, or sticker, such as the sword, the pike, the dirk, the halberd, the claymore and the poniard. As a matter of fact, a couple of foreigners entangled in a brawl without some kind of extension of the arm, or cutter, present a pathetic sight. They slap one another's faces, pull hair, stick out tongues, call names and scratch.

The Irishman, if there is no dornick to grab, will engage in hand-to-hand encounter; the Englishman or the Scotsman instinctively knows how to clo$e his hand and punch—but the Frenchman, the Italian and the Russian does not. Finding himself weaponless, he will postpone hostilities until such time as he can get his fingers on something that either shoots or cuts. I do not wish to intimate that this is to be considered a cowardly trait. It has, on the contrary, after many years of experimenting, proven to be a logical and an efficient one. An enemy, whose weazand has been well slit, usually cannot" strike back.

It is, therefore, a mystery to me how a mem-, ber of a Slavic race has become the most perfect technician in the world in the art of glove fighting—although perhaps it is no more surprising than that another Lithuanian, William Burke (ne Burkauskas) has become Open Champion of the United States at a game invented by the Scotch in the North of Britain to kill time between burning heretics and eating porridge.

It is, however, no mystery at all to anyone even slightly acquainted with Slav characteristics (as indicated by their art, literature, music and drama) that impeding, baffling and frustrating Sharkey's marvelous physical skill there is a hair-trigger hysteria, a mental vertigo, a fundamental morbidness which, at some point during combat, changes him from a cool, methodical, calculating and confident boxer into a phrenetic, unbridled gibbon, who whirls around the ring in a frenzy of passion, like a daft teetotum weeping, tearing his hair, cursing and gesticulating.

For the low emotional threshold (a term invented by the late psychologist, Dr. Max Schlapp) is characteristic of the Slavs, the Latins and the Franks. Europeans are not players of games in the light hearted sporting sense. The French break canes over the noggins of rival onlookers at international soccer matches; the Italians produce sharp implements from their bootlegs, and throw them; the Slavs are a gloomy lot. They never seem to have much fun at anything. They are not any good at contact games in which they are liable to come into violent collision with one another. It gets them too excited.

And now, my dear Mrs. Applethwacker, class is dismissed; and I feel sure that you are better prepared to comprehend the Lithuanian emotional instability, of which I am about to relate some of the more charming examples. The point that I will try to make is that an admission ticket to any Schauspiel in which Sharkey is the chief protagonist promises tears, extravagant gestures and a drama of the unexpected.

The most recent and edifying of such spectacles occurred in Brooklyn one evening last Autumn. Sharkey was boxing that super baboon, Primo Camera in an important engagement—important, because failure meant that Sharkey would have to relinquish his position as Schmeling's foremost challenger—and in the course of events, sometime during the fourth round, he suckered the big monkey into an opening, and whistled his left hook against Camera's chin with a resounding thud, which was immediately followed by a terrific crash as Primo collapsed flat on his back. It was a happy moment; some thirty thousand spectators arose, bawling their approval.

The referee, Gunboat Smith, a former fighter himself, began the count while Sharkey duly retired to a neutral corner. At three, Camera turned and looked about him with a delightfully idiotic expression on his enormous face, which was made no prettier by the red gum mouthpiece protruding from his mouth. He was hearing the birdies. At the count of five he arose. Sharkey came flying across the ring to administer the coup de grace while the great ape was still decently befuddled. But Camera, viewing the approach of something that must have looked like an avenging angel, cautiously sank to one knee again.

Now the fun began. The referee took up the count, where he had left off, as provided for by the rules of the New York Commission. Sharkey began to scream at the top of his lungs that Camera was out, that his opponent had disqualified himself by returning to the floor without being hit.

Tableau: Camera on one knee still looking non compos mentis, the gray-shirted Gunner quietly elevating his hand, and paying no attention to the now uncontrollably enraged Sharkey who was waving his arms, pointing first at Camera, then at him, and then to the high Heavens, while he hurled into the night whoops of rage and complaints that he had knocked Camera out legally, and that he was being swindled. The prize fight had suddenly become Ten Nights in a Bar Room. Better was to follow.

(Continued on page 76)

(Continued from page 32)

At nine, Camera arose, still goggling and rubber-legged, whereupon Sharkey turned, and tried to run right out of the ring. Cowardice has been advanced as a motive, but there is no cowardice in the man. He had merely reverted to type, and had become an excitable foreigner who, under the impression that he was being homswoggled, was picking up his marbles to go home. (The boys will be doing that in California during the Olympics all this summer.) If he had succeeded in leaving the ring he would have disqualified himself automatically.

Enter comedy. Sharkey's manager is fat John Buckley of Boston. To John, like an old man of the sea, an enormous bay window has fastened itself —a massive and useless affair. Useless, at least, until that particular evening when it saved the show—not to mention Sharkey. With his fighter far gone in hysteria, Buckley had a flash of pure managerial inspiration. He thrust his great belly through the second and third strands of the ropes, and the fleeing Sharkey rebounded from it like a fourteen-inch rifle hitting the recoil cylinders. Twice more Sharkey came flying off this veritable wall of sanity, the last time turning around just in time to meet Primo, whose wits had returned sufficiently during this performance to permit him to come over and essay a few menacing motions. It took Sharkey three rounds to calm down, after which he gave the big Pituitary an unmerciful beating. This just gives you an idea.

But bless you, Mrs. Applethwacker, the reason you and I love Sharkey is just because he is like that. Der Mensch hat Temperament as the boys say on the Nevsky Prospekt. Ten cents a dozen for those pugilists to whom a fight is a fight and just that, a business proposition to which they bring a desire to do no more than get it over with quickly and safely. With Sharkey each fight is an event, each match a cause. He fights with his emotions as well as his fists, which is probably one reason why he may never be the world's champion. If he cannot work up a white hatred for an opponent, it's no soap. Schmeling he despises, which is why I wouldn't miss their forthcoming meeting for the gift of a never emptying barrel of Würzburger. On Sharkey's part this will not be a prizefight for a mere championship. It will be a crusade.

Did you catch him against Swooning Phil Scott in Miami, three winters ago, Mrs. Applethwacker? Of course you were there. Everybody was. Knowing that Scott was a notorious foul claimer and a little bit of not all right in the midsection, Sharkey hit him low enough to dislocate his kneecap, and when Scott swooned and refused to continue, Sharkey stood over him cursing him in Billingsgate, and in good old United States Navy.

That night, Sharkey was completely insane. I recall that he also looked a little screwy one night in Madison Square Garden, three or four years ago, when Jack Delaney dropped his hands to his side, and let Sharkey knock him out. The punch was legitimate, but the invitation looked open to criticism. Anyway, Delaney went crawling around the ring on his hands and knees like a man looking for a collar button, and Sharkey went slinking weirdly along the ropes, pulling himself along on the top strand, and weeping. It looked like one of Hogarth's drawings of Old Bedlam. And who can say Sharkey was not a little daft the time he himself dropped his hands while he was in the same ring with Jack Dempsey, and turned his head aside to complain to the referee. Naturally, Dempsey knocked him out. But that was just the climax to a very foolish evening anyway. Sharkey gave Dempsey a terrific one round beating, and had him on the verge of a knockout. He could have outboxed him for the rest of the fight winning easily. But he suffered sudden delusions of grandeur and thought that he could slug it out with Dempsey. That gives you an idea too.

He wept when he defeated Harry Wills on a foul. He was in a terrible passion when he knocked out Maloney. He was crying tears of joy when he stopped Tommy Loughran with a looping right to the temple; and two years ago, the night that he fouled Schmeling into the Championship of the World, he sat in his corner with his head sunk upon his chest, brooding bitterly over what seems to be his fate. ... It was oddly enough the fate of the man whose name he chose for his nom de boxe, Tom Sharkey, a famous heavyweight who fought in the days of Corbett and Fitzsimmons—who fought them all and was never champion.

Sharkey's temperament works both ways. It keys him up to amazing performances, performances not always calculated to advance his claim but always good entertainment, and it lets him down dreadfully against the Riskos and the Heeneys, the Christners, the Mickey Walkers, and the Mike McTigues, small men, or second, or third raters.

Into what imbecilities Sharkey's hysterical nature will lure him in his forthcoming match for the heavyweight title—his fourth opportunity, incidentally, one can only surmise. Schmeling's Teuton calm, his doggedness, his great courage and his ability to blot up punishment are all calculated to make Sharkey lose his head, foul out, jump out of the ring, get himself knocked out, commit mayhem, or expire publicly from the force of his passions. Or, finding himself on the losing end, as he undoubtedly will, Sharkey may, like Rumplestilzken, stamp his left foot right through the ring floor, seize his right foot in both hands and tear himself in two, a spectacle that will be reasonable enough at twenty-five, at fifty or, by Jove—at a hundred dollars a ticket.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now