Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe pitch shots

ROBERT T. JONES

In pitching, a player may either play a straightforward stroke, (striking the ball a descending blow) a blow which is directed along the line of the intended flight, or he may play what is called a "cut" shot which is executed by drawing the club across the line of flight and striking the hall very nearly at its nethermost point. Each of these two shots has its advantages.

The straightforward, backspin shot—given conditions close to normal—meets most requirements so long as the length of the shot and the loft of the club will permit a full shot to be taken. With the mashie this shot can be played with safety down to distances of about 125 yards. The loft of the club alone, striking a descending blow, imparts sufficient backspin when travelling at high speed. This kind of shot, when struck properly. flies in a straight line directly for the objective. So far as direction is concerned it is by far the more reliable shot to choose.

But when the distance becomes shorter, this method fails to produce enough backspin, or to secure enough elevation, to bring the hall to a quick stop. It becomes necessary either to choose a more lofted club or to vary the method of using the one already at hand. If the mashie is still to he used the procedure is something like this: The stance becomes more open, the right foot being advanced nearer the line of flight, and the shoulders turned so that the player is facing more nearly toward the hole. The face of the club is laid off and the hall placed farther forward. In starting the stroke the backswing becomes more upright and there is a lesser turn of the body than is present in the longer shots. When the ball is struck the club face, still open, is drawn in across the ball. This motion imparts backspin and at the same time a sidespin which causes the ball to fade slightly from left to right. It is a shot that stops very quickly after striking the green.

It is difficult to explain why this type of shot should be more accurate in range than the other shots I have described. This, however, seems to be the consensus of opinion and, once accustomed to the method, it becomes surprisingly easy to control both the "fade" and the direction of the shot. The chief difficulty is that it is not, like the other, a natural stroke. The execution being a bit more complicated, the effect of bad timing or of any inaccuracy in hitting—caused by anxiety or tightening—is more apt to be a little, or wholly disastrous.

As a rule it is better for average players to prefer the straightforward shot, wherever it is possible.

When attempting to play a quick-stopping shot, with lots of backspin, it is difficult for even an expert to dispel from his mind the idea that he must hit the ball very sharply. The natural conception of the spin-producing stroke is one involving a picture of the club-head travelling at terrific speed across a point on the surface of the ball, gripping that point, and imparting to the ball a very rapid rotary motion.

I suppose that I have spent hours in practicing short niblick and mashie-niblick pitches, always with this ■wrong idea in my mind. Everyone knows that the shorter the shot the more difficult becomes the problem of bringing the ball to a quick stop. The matter of stopping the longer pitches—the spade and the mashie shots—has never worried me. But I have always wanted to produce more spin from the shorter distances, and have too often tried to obtain it by laying the club face well back and attempting to rip the bottom off the hall. Of course, when everything is just right, a great amount of spin can be produced in this way, but there are two things wrong with the method—and two wrong things are enough.

In the first place, since the swing is far more vicious than would be necessary if the ball were to be struck in a normal way, the player runs a great risk, in case he fails to strike low enough. This risk becomes appallingly great when the lie of the ball is close. I have seen any number of my shots, half-topped, go yards over the green. The mental state of the player, when he fears this sort of thing, gives rise to the second objection. In nine cases out of ten, in order to avoid a half-top, lie will strike too low, meet the ball near the top of the blade and provide an ample cushion of grass between the club and the ball, thus spoiling the clean contact which he needs to produce spin.

In short pitches, one of two conditions exist—the ball is teed up or it is lying close. In the former case the spin is as easily produced by a leisurely swing which can be accurate and which has the advantage that it does not risk absolute ruin in case the contact is a little high. If the lie be in heavy grass, backspin, to any useful degree, becomes out of the question, and the only hope is to lob the ball with as much elevation as possible, allowing: it to fall lightly on the green, short of the hole. If the green be soft the ball will likely ,land softly, if the green be hard, it is too bad, but it can't be helped.

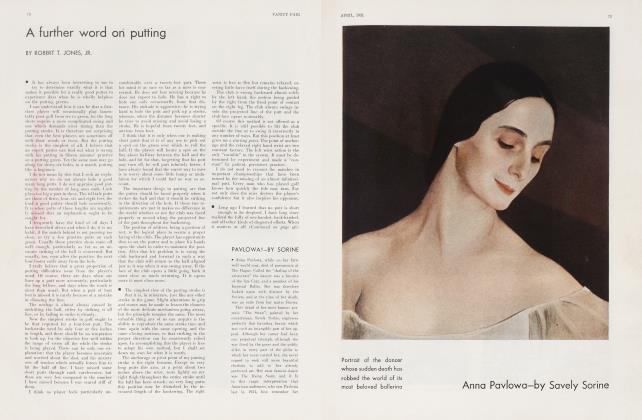

I like to see a pitching stroke that is smooth and unhurried, one that strikes evenly through the ball and does not appear to accelerate too violently at, or just before, impact, giving the impression that its author is afraid that the ball will lack backspin. To my mind, the best pitching stroke in golf is that of Gene Sarazen. Gene, from the shortest distances, always spanks the ball firmly up to the hole with plenty of backspin, yet his club appears simply to float into the shot.

Naturally, the very short pitches cannot be played exactly like the longer shots, for the force of the blow is less, and the spin-producing force must be exaggerated by greater loft of the club and by striking the ball nearer the bottom—nearer the point where it rests upon the ground. The direction of the blow is slightly downward still, but I cannot think of a better way of describing this shot than by saying that it should be an effort to "cut the feet off the ball". I know there is a more or less general prejudice against the use of a niblick for anything but long grass or bunker shots, but, nevertheless, I strongly advise its use whenever it would lie necessary to lay off the face of a mashie-nibliek in order to obtain the needed amount of loft and cut the feet off the ball.

(Continued on page 64)

(Continued from page 54)

In playing a pitch shot of any distance it is most important that the backswing be of ample length and that the left wrist should be very active. It is the failure to follow these two rules that makes the average golfer unable to pitch well. In watching a number of short shots played to any green, in amateur contests, one will see many heads go up and many clubs dash into the ground behind the ball—all because the owners of these heads and the wielders of these clubs failed to accomplish a long, smooth, rhythmic stroke.

It must be remembered that backspin is applied to the ball whenever it is truly struck by a downward blow with a lofted club. Once the player gets this idea fixed in his mind he is on the road toward learning to control his pitches.

I have heard dozens of teachers and writers say that "The length of the shot must he governed entirely by the length of the backswing". I shudder every time I hear or read anything like that, and hope that the average golfer will pay no attention to it. He has all the trouble in the world playing a half-shot anyway and nine-tenths of his trouble is caused by heeding this advice. Just as soon as anybody begins to think about cutting down the length of his swing, he throws the door wide open for tension to come in and rhythm to go out.

Time and again I have seen a man try to play a half-shot by taking a very short backswing and whipping the club through viciously in an effort to hit the ball crisply. The results are, first, a hurried, unrhythmical backswing; second, an immediate start downward which can only be described as a jerk; third, a quick stabbing blow, and fourth, as might have been expected, a rotten shot.

The proper swing for a half-shot is somewhat shorter than that required for a full shot, that is, when the club is being played to its limit. But it is not shorter because it needs to be shorter, but because it does not need to be as long. It certainly can be as long without hurting anything. The point of control comes when the time for hitting arrives, and in the case of the expert this control is obtained by doing exactly what the shorten-the-swing fellows tell us we ought not to do—that is, by easing the punch. This does not mean that the ensuing contact is not crisp. It certainly is and will always be crisp so long as the timing is good and the wrist action supple. The firmness is supplied by the flick of the wrists as the club-head nears the ball. The good player strikes crisply but he does not strike viciously, or hard.

A longer swing permits a player to be leisurely. He has plenty of time to get his club moving without having to yank it about. If he is playing something less than a full shot—an easy shot—he simply waits a bit longer to hit, and hits more gently than he would otherwise hit. When relaxation is perfect he has the feel that the club-head is merely floating into the ball.

I have always thought that Max Marston was a fine example for a beginner to watch as there is, in his swing, an appearance of extreme leisure, of having all the time in the world, which the duffer ought to copy. And let him also observe the length of Max's backswing when he is playing a so-called half-shot. Max could, with the same swing, knock the ball a mile.

The whole idea, it seems to me. is to encourage the player to swing the club-head. A longer backswing gives the player a feeling of freedom and ease, which extends even to his state of mind, and so relieves a good deal of his anxiety over the success of the stroke.

And this same idea of ease is an all important one. Indeed, most players should learn that there is only slightly more complication in the stroke to be used for chipping than is encountered on the putting green. It must, perforce, be a little longer, and account for a slightly more forceful handling of the club, but everything said with respect to putting—the easy, comfortable position at address, the relaxed feeling in the legs, and the mobility of the body—applies also to the short chips. In putting, we must try for a long sweeping stroke, wherein the club is swung without the least trace of hurry. In the chip shots we must try for precisely the same stroke.

NOTE: This article by Bobby Jones is published with the permission of the Bell Syndicate, Incorporated.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now