Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

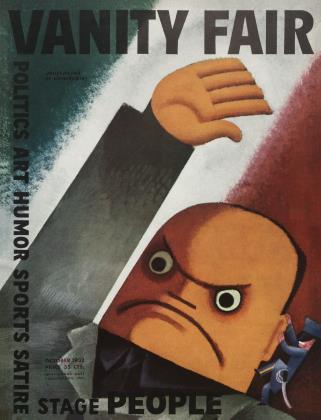

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowUNCLE SHYLOCK'S DILEMMA

DREW PEARSON

■ Not long ago President Hoover stood in front of a microphone and told a nationwide audience that: "These debts must not be cancelled." Secretary of State Stimson, backed into a corner during a press conference about the same time, said: "There is no connection between Europe's reparation agreement at Lausanne and the war debt agreements with us." Senator Claude Augustus Swanson, Virginia Democrat, returning from a Disarmament Conference forty miles from Lausanne, chewed on a long black cigar and drawled: "They want us to pay their war bills over there, but we're going to fool 'em." Senator David Aiken Reed, Pennsylvania Republican, fidgeting in a big leather chair in the Military Affairs Committee Room, said: "We'll lower the British interest rate, but that's all."

And so on . . . through most of the Cabinet, the Senate, the House of Representatives. . . . No matter what the party, no matter who the person, an almost complete unanimity— speaking for publication—that war debts cannot be cancelled.

But, speaking not for publication, it is a different matter. Not for publication, it has gradually percolated to the brain of the Administration—in fact even to the brains of a few isolated Congressmen such as the Demosthenes of the Senate, William Edgar Borah— that no matter what the President or Congress may do, say, or feel about war debts, the United States, in the end, is going to pay Europe's war bills.

It is going to pay them one way; or it is going to pay them another. Either European governments are going to default; or else the great mass of bonds and credits extended to Europe by American investors will remain unpaid. Either the American tax-payer will pay the war debts in higher taxes through the Federal Treasury; or else the American investor will pay them through loss of coupons and principal on his loans to Europe. One or the other is going to make the supreme sacrifice; and there are some economists who believe that both war debts and investments will run down the waste-pipe of Europe's financial sink before the present economic maelstrom has subsided.

The story of how this realization finally percolated to those who run the wild horses of bond issues and high taxes down Pennsylvania Avenue is a drama of personal prejudices and political paradoxes. It gives some indication as to what Congress and the Administration will do when both run head-on into the stone wall of the war debt problem, after it has been decided whether the Democrats or the Republicans will endeavor to collect from Europe during the next four years.

In opposing cancellation of war debts, Herbert Clark Hoover has been completely consistent. He was the most finicky and recalcitrant member of the War Debt Funding Commission. He was the chief opponent of large reductions to the Allies. Sometimes it required several sessions of the Commission and long arguments by his colleagues to bring the then Secretary of Commerce around; and sometimes after they thought they had convinced Mr. Hoover, they discovered next day that they had to do all their convincing over again.

Andrew W. Mellon, then Secretary of the Treasury, was only a trifle less parsimonious. Throughout the negotiations he sat, almost immobile, two fingers of his alabaster hands holding a thin Pittsburgh stogie. When he spoke it was final, and he never wavered from the view that the Allies must pay.

In fact neither Mr. Mellon nor Mr. Hoover wavered from that view as late as May 5, 1931 -just one month before the latter proclaimed the inability of Europe to pay, and proposed a moratorium on all war debts. It was on that date that Mr. Mellon told the American Association of Bankers of his "confidence in the willingness of Europe to honor its obligations whether these be debts arising out of war or out of the post-war period." And two days earlier President Hoover had warned the International Chamber of Commerce, through the medium of a press conference, that the United States intended to stand pat on war debts.

■ Two other figures also played major roles in that first act of the war debt drama. I hey were Frank Billings Kellogg, nervous, dynamic Secretary of State, and S. Parker Gilbert, shrewd Under Secretary of the Treasury, later Agent General of Reparations. It was Parker Gilbert who sat in Berlin after the Dawes Plan had brought some degree of stability to the reparations tangle and watched German states and German municipalities and German public utilities and German industries loading up with American dollars in one of the greatest orgies of borrowing the world has ever witnessed. Much of the money was spent for productive purposes, but much also went for such luxuries as swimming pools, amusement parks and public works yielding no revenue; and all of the money served as a release for other German funds to be transferred as reparations to France and Belgium, and through them in turn hack to the United States, in the form of war debt installments.

It was a circle which ended nowhere, which served only to preserve the myth of prosperity, and which the bankers either could not see or did not want to.

Parker Gilbert, however, saw it. And having watched this orgy of lending, and having received complaints even from the central German Government that the states and municipalities were over-borrowing, he issued a public warning on October 20, 1927 in which he said:

"If the present tendencies are allowed to continue unchecked, the consequence is almost certain to be a serious reaction and depression, a severe shock to German credit at home and abroad."

Some time before this Mr. Gilbert had issued a private warning to his old friend and law partner, Paul D. Cravath, then attorney for several banking houses.

"I am constantly amazed," he said, "at the recklessness of American bankers in offering to the public the securities of German states on the basis of the purely German view of Article 248 of the Treaty of Versailles."

This purely German view was to the effect that private debts had priority over reparations and that American bondholders would be paid before Allied war claims were satisfied. This German view was not held by France and other Allied countries; nor was it held by the Secretary of State, Mr. Kellogg. And in all replies sent to bankers asking if the State Department objected to loans to Germany, Mr. Kellogg carefully pointed out the conflict between private loans and war debts.

"These risks which obviously concern the investing public," Secretary Kellogg warned, "should, in the opinion of the Department, be cleared up by you before any action is taken. If they cannot be definitely eliminated, the Department believes that you should consider whether you do not owe a duty to your prospective clients fully to advise them of the circumstances."

According to Parker Gilbert, however, this advice was not given. Writing to Paul Cravath, November 3, 1926. lie said:

"It does seem to me difficult to justify the action of the American bankers in offering securities to the public without giving the slightest hint that the German point of view is not accepted by the Allied Governments and that, in fact, the Allied point of view is diametrically opposed."

® All this fell on deaf ears. The public was out to buy anything and it did. It bought German bonds up to a total of $1,300,000,000, and the banks extended an additional half billion in short term credits. This kept on until the Coolidge Bull Market caused the public to desert bonds for stocks, shortly after which the financial avalanche, frequently referred to as the depression, brought on the second act of the war debt drama.

The curtain rose on this act sometime between May 5, 1931, when President Hoover and Secretary Mellon were reiterating their opposition to war debt cancellation, and June 20, 1931, when President Hoover announced his moratorium. The curtain struggled up by fits and starts, the two chief stage hands being Ogden Livingston Mills, then Under Secretary of the Treasury, and Henry Lewis Stimson, still Secretary of State. Mellon looked on from the wings. He approved but did not applaud. He was then in Europe, and saw for himself that if something were not done to bolster Germany and Austria, European collapse would be general.

■ The moratorium began the gradual eclipse of Mr. Mellon and the gradual rise of Mr. Mills. That young, pink-cheeked, hard-working gentleman went back and forth between the Treasury basement and the east wing of the White House like an animated shuttle cock during those fervid days, until gradually he became so essential to the President that Mr. Hoover scarcely shifted his feet or tied his necktie without calling upon him.

It was Mills who acted as personal interpreter for the President during the HooverLaval conversations, and it was Mills who drafted the Hoover-Laval agreement and took it to the French Premier for approval, and finally it was Mills who convinced Mr. Hoover that the Allies could not pay their debts and persuaded him to propose an extension of the moratorium. To this end the big chiefs and the little braves of both political parties were summoned to the historic Lincoln study of the White House, where as a sort of prelude, domestic banking reforms were discussed. Then the moratorium extension idea fell out of the bag quite as if by accident and landed on the big toe of Senator Borah. The Senator jumped. The President and Secretary Mellon sat silent. It was not their party. Talk as loudly and as rapidly as he could, however, Ogden Mills was unable to drown out the wails of Senatorial anguish and they have been reverberating over the radio ever since.

With that event was ushered in the third and present act of the war debt drama. Probably war debt historians will dub it the Era of Congressional Obstinacy. Certainly it began that way. In December, 1931, President Hoover sent a message to Congress asking for the appointment of a debt-funding commission in order to scale Europe's war debts. Both Houses laughed. Then he asked approval of his one year moratorium, and got it only because the leaders were pledged in advance. On the end of the agreement, however. Congress tacked a rider making it clear that Europe's period of financial grace was to be for one year and no longer. A little later when the Washington Post suggested that Mr. Mellon had been sent to London as Ambassador in order to discuss war debts, such a howl arose in the Senate that both the White House and State Department almost turned somersaults in their haste to deny the story. Finally, when European debtors, acting on the advice of the State Department, gathered at Lausanne in order to draw up a war debt program to submit to the United States, Secretary Stimson shook in his shoes at any wrong interpretation which Congress might place upon this.

And yet all this time Hoover knew, and Stimson knew and Mills knew that Europe will default either on war debts or private debts—possibly both; that either the American investor will be saddled with part of the war debt burden, or the American taxpayer— possibly both.

Germany cannot pay. France will not. England and Italy will make an effort. The smaller countries cannot. Great Britain will put up her last farthing to protect her credit. She has to. She has millions invested in Latin America, the Far East and Europe—millions which are in jeopardy—millions which never would be paid if the debtors could point to the fact that Britain, great lending country of the world, had made defaulting fashionable.

In France war debts are a sore and bitter subject. They arouse editorials on Uncle Shylock and inspire headlines reading: "Not one Centime for the Gangsters." French bitterness is equalled only by that which exists in both Houses of Congress. There are, of course, some Congressmen who would like to cancel war debts, but dare not. They do not court political suicide. Their constituents, especially in the south and west, can see no reason why they should be overtaxed to pay Europe's war costs. And for the most part the opinions of individual Congressmen are just as vehement.

This view is not changing. The Congress which meets one month after the November elections will be just as obstinately opposed to war debt reduction as that which laughed down Mr. Hoover's proposal for a debt funding commission. European nations have 37 days from the election on November 8, to the date on which their first debt installments—following the end of the moratorium—are due on December 15. During that period they have two alternatives. They may take advantage of a clause in their agreements permitting suspension of payments on principal; or they can ask for debt revision.

Only one road out of this impasse has been suggested. Its advocate is the Senior Senator from Idaho. Senator Borah is an aloof and unusual individual. Sometimes he sits in his office for hours mulling over certain ideas. Gradually these ideas crystallize into convictions. After they have reached the conviction stage he puts them down on paper; and after that he spends additional hours rehearsing his speech in a voice which causes those who pass the closed door of his office to turn in wonder. Finally he takes the finished product to the floor of the Senate and before a gallery packed with members of the Diplomatic Corps and the élite of Washington society, delivers a masterpiece of oratory.

Recently, Borah has been spending long summer evenings on the cool lawns and verandas of Secretary Stimson's. There, in the absence of Mrs. Stimson, the Senior Senator from Idaho has shown genuine and unheard of tendencies to abandon his old policy of austere isolation. He has indicated his willingness to have the United States play a more active part in the Maelstrom of Europe, and he has further indicated his willingness personally to help in putting this idea across to the public.

This idea, the Senator summarizes somewhat as follows:

The Allies will no longer pay the United States. They will no longer pay, first because they don't want to; second, because the Smoot-Hawley tariff wall prevents payments in goods; third, because the concentration of gold in the United States makes the transfer of bullion extremely difficult for every country except France.

These war debts, on the other hand, represent real sacrifices made by the United States. They represent also, not money lent the Allies during the war, but only after the Armistice. This country, therefore, should get something in return. It should get—failing cold cash—at least some moral victory. It should get a belated fulfillment of Woodrow Wilson's ideal of a more stable and peaceful Europe. It should use the war debts as a bargaining lever with which to pry loose Europe's staggering burden of armament and rectify the wrongs of the Versailles Treaty.

This is Borah's program. In it, strangely enough, he has the support of the man with whom for the past three years he has so vigorously disagreed—Herbert Hoover. He also has the support of the State Department, most of his colleagues and a large number of the American people.

Whether he has the support of those in Great Britain who favor a large navy; or those in France who maintain that the Republic should have an army second to none; or those in Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Jugoslovakia who support an army far larger than that of the United States, is of course, another matter. One thing, however, is certain. Regardless of the European investments of individual Americans, the temper of Congress is not now favorable to burdening the United States with the costs of the past war, as long as Europe can afford to pay for the next. Congress has got used to the role of Uncle Shylock and likes it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now