Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

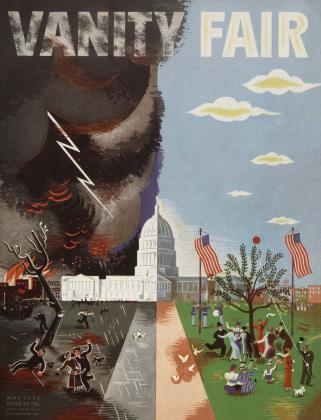

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWHITE HOUSE HOPES OF 1936

DREW PEARSON

For many weeks prior to the time he left the presidency on March 4, Herbert Hoover besought Republican leaders to meet with him at the White House and plot the course which the Grand Old Party must follow to redeem Republicanism and the Nation in 1936. And for an equal number of weeks the leaders of his party dodged that invitation.

They did not exactly say: "No." Presidential invitations do not usually get that kind of an answer. But they found every conceivable excuse for postponing, side-tracking and out-maneuvering the meeting.

Behind this game of hide-and-seek between the titular leader of a powerful political party and his powerful party henchmen was the most important issue facing Republicanism today: Can Mr. Hoover come back? Behind it also is the fact that today, four years from the next presidential inauguration, four years during which there may be prosperity or depression, peace or war, success or failure, four years during which our entire structure of government may change—already certain gentlemen are maneuvering into position on the political springboard from which they can make the great sacrifice for party, for people, and for country.

This jockeying for most favored position four years before the next presidential race has come to be almost routine politics in recent years. Woodrow Wilson, even as an academician at Princeton, went in for a certain amount of it; while silent Calvin Coolidge, renowned as the luckiest president that ever lived, was not satisfied to leave everything to luck and had his old friend Dwight Morrow give away thousands of Cal's speeches as a build-up before the 1920 convention which brought him the vice-presidency. It remained. however, for Hoover the Promoter to establish real technique in putting across advance presidential ballyhoo. He began working at it shortly after he entered the Harding Cabinet when George Akerson. later his secretary, was hired to radiate synthetic cordiality to all worshippers at the Department of Commerce, when Hoover luncheons for editors of business journals were staged every month, and when no press interview or photograph was neglected which might contribute to the efficacy of the Hoover legend.

The disastrous thing about all this presidential jockeying is that so many people take the game seriously. If their own hearts are not beating for bigger and better sacrifices, they are working for someone else whose heart is. Thus even before the next presidential race, the routine of government is warped and complicated by under cover currents meaning little to the casual observer but all pointing to the magic numerals—1936.

1936 explains many things. It explains, for instance, why the astute Senator from agri cultural Oregon, Charles L. McNary, declined to vote against the domestic allotment farm relief bill of which he thoroughly disapproved. It explains, for instance, why Representatives Rainey, Garner, McDuffie and Byrnes all walked out of the House of Representatives when the last session of Congress voted on prohibition enforcement funds. It explains why poker-playing Republican Snell walked over to bushy-eye-browed Garner at the beginning of the lame-duck session and said: "Jack, if you Democrats come out for straight repeal, my side will back you up,—" and then withdrew his support. It explains why ex-vice president Charlie Curtis jumped at the chance to head the Young Republicans, why bis halfsister, Dolly Gann, is going to continue speaking for the Republican National Committee, why ex-postmaster Walter Brown is talking about organizing an ex-office-holders' league. And finally it explains why Herbert Hoover was so profuse in extending the hospitality of the White House to the leaders of the G. O. P., and why the leaders of the G. O. P. in turn were so loath to accept.

For to accept that invitation meant that their hands were tied, perhaps for the next four years. It meant not they, but Mr. Hoover could direct the control of the Republican Party. It meant that if they sat down in Mr. Hoover's home, partook of his hospitality, the organization meeting would be dominated by him, his candidate would be made chairman of the Republican National Committee, his men would be appointed to key places, and he would be in much better position to become the Republican nominee in 1936. And finally it meant that the party leaders were a long way from being convinced as yet that the best prospect for the return of Republicanism lay with a president who had been so overwhelmingly repudiated.

So they tried to dodge the White House invitation.

In the end neither side won a real victory. The meeting took place before Mr. Hoover left office, but it was not held in the White House. After the meeting, members of the Executive Committee made obeisance to their titular leader by going to bis house and taking tea. The main event of the day, however, was the drafting of a letter to Mr. Hoover full of polite phraseology hailing him as the helmsman of their party. Among other things, the letter said: "There will be no political holiday. The Republican Party will begin an aggressive and active campaign for the election of Republicans." To some the letter was the token of honest appreciation and sincere allegiance. To others it was mere face-saving.

But one real victory went to Mr. Hoover. He succeeded in retaining as chairman of the Republican National Committee, Everett Sanders, the man be had selected to manage his own re-election campaign last year. Heavyset, lethargic of mind and of movement, Mr. Sanders was not a brilliant political strategist. Many Republicans felt he had bungled badly. But regardless of what they thought, Mr. Hoover had his way. Everett Sanders was his man and Everett Sanders remained chairman of the Republican National Committee.

Thus ended the first skirmish in the battle to answer the great Republican question mark —can Herbert Hoover come back?

In Mr. Hoover's own opinion there is not the slightest doubt about the answer. It is vigorously in the affirmative, lie feels that he was the victim of circumstance, that under any other president the country would have fared much worse. He believes sincerely that had he not been at the helm of the nation grass would have grown in its streets, lo his friends he lias confided the belief that the country did not realize the problems which faced him nor appreciate the manner in which he undertook their solution. I ime alone, he thinks, will bring about this appreciation. The contrast between his and the Democratic Administration, he feels, will bring the country to its senses, create a demand for his return in 1936.

The pros and cons of this belief must for some time remain a highly speculative and unknown quantity. However, the present indisputable fact is that Herbert Hoover, regardless of what the world may think of him. is carefully building a foundation for his renomination in 1936. Whatever his other defects, the ex-president is a careful organizer, and now. three years in advance of the next presidential convention, Mr. Hoover is evolving the same strategy which sent him to the White House in 1928.

Key man in this strategy is Everett Sanders. Equally important is the planting of Lawrence Richey in Washington. Richey is Hoover's closest and most trusted advisor. He helped to put his chief in the White House once, and he hopes to do so again. His role is to remain in the industrial East and act as informer to Mr. Hoover in the Far West. Holding down the same job in the agricultural Middle West will be Walter Newton of Minnesota, Hoover's former political secretary. Mr. Newton is the author of a political chart which particularly bucked up the defeated president after November 8 and increased his determination to prepare for 1936. The chart showed that in a number of racial elements east of the Alleghany Mountains, Hoover had gained over his 1928 vote and that far from being badly beaten he had made an excellent showing. Now, Newton will apply the same political sagacity to the middle west and keep his exchief posted regarding the future.

Herbert Hoover mellowed greatly during the last few months in office. He became more human, more tolerant, less aloof. He even unbent enough to write Senator Carter Glass a birthday letter, much to the amazement of everyone, especially its recipient. The Senator from Virginia had been one of the President's most caustic critics, and climaxed this criticism with one of the most vituperative and barbarous radio assaults of the entire campaign. In return for which Mr. Hoover sent Glass a letter paying tribute to his fifty-odd years of public service in such beautiful and obviously sincere language that it brought tears even to the eyes of the crusty old senator.

n And after he left the White House Mr. Hoover became even more human—at times almost appealing. There was something rather pathetic about the way lie cancelled his fishing trip because of the banking crisis and sat on the thirty-third floor of the Waldorf Astoria in New York waiting for his successor to ask the benefit of his advice. There was also something a little pathetic about the joy he seemed to derive out of breaking the restraint of four years of imprisonment and getting the same kick out of Fifth Avenue window shopping as the girl from Keokuk on her first visit to Manhattan. Mr. Hoover even appeared to have developed a sense of humor, and when welcoming the exiled president of Chile, Don Carlos Davila, remarked: "Well, we're both in the discard now."

(Continued on page 62)

(Continued from page 18)

The American public is quick to blame and quicker to forgive and forget. Whether four years will be enough to forget the Hoover depression, whether the ex-President is not encumbered with too many unpleasant memories, too many bad tastes in people's mouths for the party leaders to accept him as an asset rather than a liability, only time can tell.

Certainly also when 1936 approaches. Mr. Hoover will find pitted against him for the nomination of the Republican Party one of his closest former associates. For Ogden Livingston Mills has been bitten by the presidential bug, and when Ogden Livingston Mills is bitten by anything political it is a serious matter.

Little Oggie, as the incomparable Al Smith once called him, has been taking his politics seriously ever since he startled his family almost out of their blue-stockings by running around New York ringing door bells and standing at polling places as a wardheeler. Mills in those days had his unusually bright eyes fixed on a goal

a goal which he has followed relentlessly as a much disliked member of Congress, as a defeated candidate for governor of New York State, and as the man who really held Andrew W. Mellon's mental hat and overcoat while that suave and unimpassioned old gentleman was making his reputation as the greatest Secretary of the Treasury since Alexander Hamilton.

That goal was the presidency of the l nited States.

And now that he has served—with unswerving fidelity and unusual ability-one president of the United States, a determination has been firmly planted in his breast that the Republican Party could nominate no better qualified candidate in 1936 than Ogden Livingston Mills.

Athwart the path of that ambition lie at least three known obstacles—and there may be more later. One is the similar ambition of his ex-chief, Herbert Hoover. The other is the exactly identical ambition of another scion of New York's landed aristocracy, James W. Wadsworth, Jr. The third is the fact that Mills served his ex-chief loyally and well.

If the dismal trade-mark of the depression has been stamped too indelibly onto the name of Herbert Hoover to make him a successful candidate in 1936, almost equally so stamped is his ex-secretary of the treasury. For Mills really ran the financial show for Mr. Hoover and everyone knew it. He helped in the writing of the President's speeches— the best ones he ever delivered, lie helped steer his chief's circuitous route through the mazes of prohibition straddling, along the brink of a drop from the gold standard, on a politically precarious path toward war debt cancellation, and toward the goal of big business relief through the Reconstruction Finance Corporation.

Unquestionably Mr. Mills, under the circumstances, did a good job. Unquestionably Mr. Hoover without Mr. Mills would have done a much worse job. Unquestionably also, the public, unfortunately for Mr. Mills, always will have a picture of him clad in a wilted silk-monogrammed shirt, tilting a big Benson and Hedges cigar at a cocky angle, watching the United States slide down the skids of the depression.

Unencumbered by this handicap is one of New York's most astute and charming politicians who has his eyes as firmly fixed as Mills and Hoover on the lustrous goal of 1936. He is smiling Jim Wadsworth, gentleman farmer of the Genesee Valley, former Senator, militant leader of the wet contingent of the Republican Party and now a member of the House of Representatives. Oggie Mills and Jim Wadsworth for years have been polite but mortal enemies. Theirs is a hate of which only the bluest of blue-bloods can be capable. Both nurtured in the lap of luxury, Mills graduated from Harvard, Wadsworth from Yale. Both attempted to dominate the Republican politics of New York State, and both to date have failed. One reason for that failure is rivalry. Together they would make an excellent team. Mills is short on political sagacity. Wadsworth is one of the most astute politicians in the country. Wadsworth does not have to his debit, for instance, some of the strategic blunders of Mr. Mills in the last campaign. He will not have flaunted in his face as will Mr. Mills, the latter's comparison between the poverty-stricken boyhood of Herbert Hoover and the luxury-laden youth of Franklin Roosevelt, all delivered by a man who had attended Groton and Harvard along with Roosevelt and who was once indiscreet enough to tell a New York audience that he had never been forced to work for a living.

Jim Wadsworth's only debit has been a wife whose contribution to politics has been more tinged with vigor than discretion. Daughter of John Hay, one of the country's most famous secretaries of state, Alice Wadsworth is a militant believer that woman's place is in the home. During the war she headed the National Association Opposed to Woman's Suffrage, and is now honorary president of that organization for life, none of which was conducive to Jim's complete political peace of mind during his twelve years in the United States Senate. It was not on this issue, however, that the redoubtable Jim finally came to grief. His great mistake was in being six years too early. In 1927 he ran for reelection on a wringing wet platform, aroused vigorous opposition from the Republican drys, and lost out to the Democratic and wet Mr. Wagner. Now, six years later, with repeal the vogue, Jim Wadsworth is still wet, still ambitious, already has thrown his hat in the ring for 1936 and is working to build up a machine which will give him the Republican nomination. As a step in this direction he was willing to step down from the august upper house of Congress and become a plebeian Representative—just one out of the other forty-two from the state of New York. As an additional step Jim even has made overtures to Mills, and there is a report that necessity for a united front against Democracy finally has caused a reconciliation. This may last for a time; but there is room for only one Republican candidate in New York state, big as it is, and the Mills-Wadsworth honeymoon has as much chance as A1 Smith and Herbert Hoover of running on the same ticket.

(Continued on page 72)

(Continued from page 62)

So starts the race to wrest the White House from Franklin Roosevelt in 1936. There are no issues, only personalities, promoters, paid publicity agents, carefully worked out plans to keep each candidate in the public eye during the intervening three years.

So far there are only three outstanding White House Hopes—Hoover, Mills, Wadsworth. But there will be more. Especially will there be a host of dark horses for second place on the ticket—Pat Hurley, defunct secretary of war, Trubee Davison, his youthful and energetic assistant, Wild Bill Donovan, whom Hoover wanted to send to the Philippines, Young Teddy Roosevelt, who finally went there. All are maneuvering for the pole in the vice-presidential race.

And none of them will drop out. All are embued with the spirit of alleged martyrdom, which has made the American presidential race ihe world's greatest phenomenon. It has developed a passion for masochism unequalled by the fakirs of India. The goal to be attained is the hardest job on earth. It has worn out more men, killed more, subjected them to more heartbreaking criticisms than any other office high or low in any other part of the world. Yet people want it. They want it, and they begin four years in advance to plan, plot, hire promoters, maneuver politicians, spend their fortunes, ruin their health, all for the privilege of baring their bosoms on the altar of public sacrifice—the presidency of the United States.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now