Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAy Mama Inés!—the song of Cuba

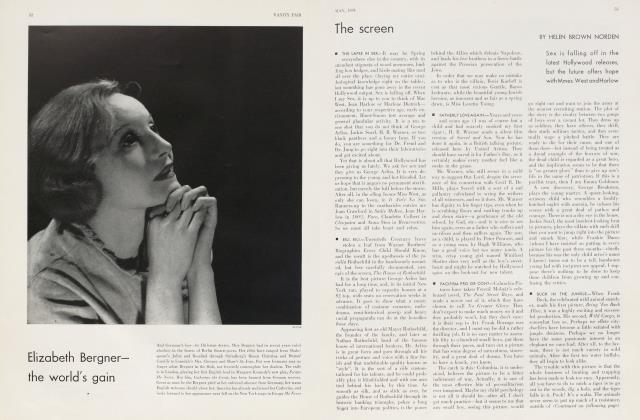

HELEN BROWN NORDEN

"Ay Mama Inés, ay Mama Inés—todos los negros tomamos cafe,

Helen, Helen, Helen—donde estas tu metida? En el barrio de Jesu-Maria Yo te busque y no te encontre"

The song of Cuba—a hundred dark throats have sung it; a thousand brown feet have danced it. 0 Mother Inés . . . all the Negroes drink coffee, drink thick black coffee. 0 Mother Inés, where are you hiding? If e have searched for you everywhere and we have not found you. IEe have searched for you in the tough districts of Jesu-Maria—and we have not found you. Oh Cuba, my mother, my sister, my beloved! I'he big steamer slides heavy and sure into the harbor and two hundred and fifty delegates to a druggists' convention rush as one man to the rail, thirsty mouths agape.

"Well, Sam, it won't be long now!"—"Oh boy, am I gonna head for old Sloppy Joe's!"

. . . "You'll be sloppy all right, kid, in an hour from now."—"Man! You bet your sweet life 1 11 be sloppy. Hold on to the wife!"

They have probably spent the preceding night—till four o'clock in the morning—getting hilariously, noisily and quite thoroughly drunk, going about it with the business-like energy and dispatch which characterize the American-on-pleasure-bent the world over. Captains of industry from Des Moines and San Antone and Egg Harbor, New Jersey— the candy king of the South, the witch-hazel czar, the razor blade magnate—cavort and caper in their paper carnival hats, blowing tin whistles and banging wooden snappers, their red-ribboned identification badges bouncing on self-made stomachs. A man named Parsons goes around saying "Vass you dere, Sharlie?" and introducing all the women, in turn, as "Mrs. Parsons." He's a scream. Another man gets a lot of laughs by saying "Mr. Razor, meet Mrs. Safety-razor," and "Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your beers." Everybody laughs and slaps their thighs. "He's good!" they say.

Outside, the sea roars black and infinite, and the wind blows cloud-veils darkly across the pale gold winter moon. The ship ploughs on through the water.

And now, on the afternoon of the next day, the tourist group comes into port. They are about to land in Havana, after an hour of waiting at anchor while little tenders chug back and forth, bringing dozens of doctors and officials and immigration inspectors and Cuban soldiers with insolent, dark eyes.

Meanwhile, the druggists assemble en masse on a lower deck and are busily tripping over each other's feet and shouting words of hearty encouragement to the somewhat wan-eyed victims of last night's party. "Well Bill, how they hitting? Listen, old man, what you need is a drink. You know, some of the hair of the dog that bit you. Hah." Havana, here we come! Is this a party, or is this a party? Quick boys, out with the cameras. Take a picture of Jim with bis arm around Gladys. Take a picture of Joe waving a champagne bottle. My God, he's a card, that one. Take a picture of the steward— say, these English are funny, you know. "Hi, blimey, 'ow's the blarsted bice 'olding hout?" 'Fake a picture of Morro Castle. Did you get it? Say, that's a dandy shot there. Yeah. Well, as I was saying, it won't be long now.

Havana, the great harlot, ancient with evil, squats on her bay of beauty. On still and tropic days, the harbor lies under the sun, corruscated with light, a hot, metallic blue, like steel tinctured with cobalt. With the faintest moan of the wind comes the change—sharp, patterned shades of colour spring out, lying distinct, side by side: pale emerald and aquamarine, the cold clear turquoise and the sapphire—the jewelled sea, painted in patches like a color chart. When the storm comes, the lathered whitecaps swirl through the sinister blues—soap bubble, Lux-like leaves of foam, veining the darker water surfaces till they look like liquid marble. The ships sail out, and from their entrails boom the deep, sustained, and almost unbearable voices of their whistles.

So the ship comes into port, bringing with her the druggists and the celebrities and the salesgirls tossing their Christmas Club fund to the winds—and the tourists, to whom Havana means only a gaudy, insensate combination of New Year's Eve and Armistice Night and the Army-Navy game.

They file down the gang-plank, holding their little pink permits in their hands, and climb in noisy bunches into the waiting taxicabs. Those who have money stay at the Nacional—where the windows stretch from the floor to the ceiling and you can sit in the center of your room and see that deep and ardent Cuban sky—and they go to the Casino every night and play golf at the Havana Country Club and drink at the Jockey Club. Those who have little money stay on board ship—"make-the-ship-your-hotel-while-in-port"—and go off together in large, disorderly groups on tours. They see Morro Castle and they go to La Playa and they visit a tobacco plantation and they buy perfume at Le Dandy and they drive by the palace and the capitol and get the university pointed out to them, and some of them visit the American Legion monument in the cemetery and come away with a mingled emotion of the Spirit of '76 and Hats off! the Flag is Passing by.

In Bermuda nice young couples go on their honeymoon and the fields are green and clean and the sands are white. And in Nassau the dowagers play backgammon and the debutantes pose for the rotogravure. Hut in Havana it is otherwise. There the blood of a different breed flows through the veins of the land; there the fateful and sweet doomed taste of the lotus lies on the lips of the city.

The tourist groups usually take one night tour, too, which shows them night life in Havana—gay Havana—and they will never get over this for the rest of their lives. In one evening they visit the Montmartre Cafe, where they see the Six Sunshine Girls from America, tap dancing in a Tiller routine— just like Roxy's, my dear—and they spend half an hour at the Casino, where they lose their shirt (say, $25) playing roulette and begin to feel like Arnold Rothstein, and they go to Sloppy Joe's and shout and scream and shake their hips and try all the different drinks they can order until they get very sick. And when they are on the boat, coming home, they tell you "Well, after all is said and done, Havana hasn't got a thing that you can't find right in the good old little U. S. A."

But it is not for them Havana weaves her magic. To them, she is the bawdy-house annex of an Elks' convention. They never see her heart—they never sense the ancient and imperishable taint of the lotus.

If you are wise, you will leave the tourists to their tours. Leave their holiday Havana alone; try instead to discover the inner city: Havana, the lovely, the indolent, the corrupt.

By all means, drive out into the country, where the vegetation is so lush that it becomes almost obscene, and poinsettias flame by the wayside and Chinese lily trees flower white and heavy-scented in courtyards, and the little pale-blue houses of the peasants lie buried deep in roses. ("Roses, roses all the way and myrtle mixed in the path like mud. . . .") Stop at the little pottery factory, where intolerably old and decrepit mules stumble in an eternal circle, turning the crude mixing wheel. Then go perhaps to El Sitio and wander through the gardens, where orchids clutch, delicately malignant and perilous, to the trunks of the tall trees, once in four years to blossom forth their evil petals of lavender and spotted yellow. On a long bench stand pots of the fragile green "sensitive plants", which shrink and close in virginal secrecy at the touch of a human hand. There are also banana trees, cocoanut palms, bamboo trees, pineapples, castor beans, guinea and elephant grass—and great fields of lilies and roses. In the yard strut the fighting cocks, each one tethered by one foot to a peg in the ground, arching their proud tails and stepping delicately.

Cock-fighting is a great Cuban sport, as well as horse-racing and that fastest game in all the world, jai-alai. The birds are groomed and trained as carefully as prizefighters, and before important matches they are fed a heady mixture of alcohol and ammonia—which is enough to make anyone want to fight, even a chicken. Two husky looking white birds are brought out, clucking with a great show of innocence and bobbing their heads under the arms of the black boys who carry them. Let loose in the pit, they prance and leap and lunge and sidestep with miraculous swiftness. They lower their two heads till they almost touch, on a parallel line, and the bright beads of their eyes are ever alert and darting. Often the combat lasts but a few seconds. Then a well-timed leap, a flash of the steeltipped chivalric spurs—and the cock triumphant crows his battle cry over the reddening feathers of his slain opponent.

(Continued on page 65)

(Continued from page 47)

Sweet Chanticleer, bring forth the dawn again!

At night you can wander down in the Chinese quarter of Old Havana. The inhabitants are oddly at variance with their Manhattan brethren. Here are no stoic enigmas, no amber slinking—but instead, laughter and a light touch. You may eat, if you like, ambrosial concoctions of chicken and fresh almonds—as opposed to the monotonous chop-suey standard of American Chinese restaurants—and the proprietor, practically convulsed with laughter, will bring out bottle after bottle and insist on your trying a glass each of rose wine, raisin wine, rice wine and sharp, pungent Chinese whiskey—all of which you will do with alacrity, anxious, of course, to do your duty as guests. Afterward, treat yourself to the amazing spectacle of the Teatro Venus, or Shanghai, where practically the entire Chinese population goes every single night to sit and watch in rapt delight the "blue movies", which may be found in almost every section of Havana, and the manufacture of which is a profitable minor national industry.

The Arabian quarter is smaller than the Chinese, but equally glamorous. There you drink the clear and colourless arak and eat chopped meat rolled in cabbage leaves and covered richly with thick sour cream. Sloeeyed lads slip in and out and peer at you—and nubile damsels with pale copper skins and kohl-dark eyelids may be glimpsed for a fleeting second.

In the city the dark, warm life throbs with an endless ease and grace. You can sit at a sidewalk café and listen to its beat. You can stop, very still, for a while in the street and feel it in the process of absorption through your body. There are moments when you can taste it on your lips. And once you feel this essence of the city, once you sense this quality of flowing, you have it forever, nostalgic and softly burning, in your veins.

Later, drop in at one of the Cuban taxi dance-balls. It will be crowded, not only with lovely Cuban girls, but also slender-eyed achinadas—Chinese and Negro—and mestizos, or mulattoes —gracefully turning the ballroom into a boudoir as they dance a modified rumba with their customers. Between dances, the mari-machos stroll arm in arm with their particular and chosen amigas. Theirs are the classic, sterile songs of Lesbia. But it never interferes with the pursuit of an ancient trade.

About four o'clock in the morning — (Cubans never seem to go to bed. No matter what hour of the night it may be, the city is always alive, and there is music and dancing)—drive outside the city to La Frit a, the Cuban equivalent of Coney Island. Wander idly in and out of various assorted bodegas and dance-halls and places of amusement. Los Tres Hermanos has the best rumba dancers: a mulatto girl with quick, dark eyes and a tall black buck, magnificently built. The girl crouches on all fours on the floor, laughing softly. Her torso waves impertinently, and she arches her back like a cat. Behind her prances the buck, teeth gleaming, eyeballs flashing, leopard-footed. A flicker, a shining, a swift, pure motion in poetic line. He leaps lightly astride and back again—like a bird. And the dance goes on. Figures which in other bodies would be vulgar, here become a part of the one flexible beauty.

Groups of Cubans sit around at little tables, watching the dance. They sit for as long as half an hour without saying a word to each other, sipping their drinks lazily. Yet they never look bored nor seem tired. It is this infinite capacity for relaxation which contributes much of the deadly charm of Cuba. This land, whose heart beats to the cadence of the rumba—the most toxic music in the world—has managed through some secret, unblessed magic to achieve at the same time a synthesis of extreme stimulation and utter relaxation. One can feel it in the streets at night, particularly. Stand on a balcony and listen to the city. Here is a life constantly beating—but not the life one hears on the streets of New York—or the streets of Berlin —or the streets of Paris, even. There is noise in the street—but it is not noise. Voices murmur without cessation, the maracas shake out their insinuating song, dice click, footsteps patter—but it is all a narcotic softness, a warm harmony.

"Ay Mama Inés, ay Mama Inés— todos los negros tomamos café....

Acknowledged as the best rumba dancer in Havana is Mica of the Moulin Rouge. ("Others call thee gypsy, Bombyca, only I call thee honeypale".) She has that pale brown skin, called café-con-leche, and her muscles ripple in fluid music. She is like a snake: you sense the power and the unerring control beneath the curve of beauty.

Stay away from the Habana Yacht Club, the Almendares, and the tea dances. They are the sort of places which are the same the world over, and unless you are the type of American who goes to Paris and spends all his time hanging around the Ritz bar with other Americans, there is nothing in them for you. (Of course, there is always the possibility that these Americans like to be with each other.) You get none of the real, innate life of the country from places like these.

Spend most of your time sitting for hours on end at obscure little sidewalk cafés in Old Havana, watching the chulos stroll in with their girls, the hetairas. You can tell them anywhere—the short, wiry build, the padded shoulders, the pearl gray fedoras, the deep pallor of their skin and that dark, hypnotic emanation from their eyes. They are self-contained and expressionless, with casual lips and graceful, cruel hands.

Their profession is termed the lowest in the world. Yet Walt Whitman once wrote the lines "Not till the sun excludes you, do l exclude you!"

Among the girls—dark, soft and liquid-eyed—there may be one like Lucrezia, with a face that looks more like Norma Shearer's than does the latter's own. The same pure line of profile, cut out with a sharp knife: the chiseled nose, the classic lips, the narrow, delicate line of cheek and pointed chin—and the turquoise eyes. She is a native Cuban, too, and a naive child of vice, with that dreadful innocence which distinguishes the authentically depraved from the virtuosos. With such childlike eagerness as this, the ardent-limbed maidens of ancient Athens must have entered upon their curricular duties in the preparatory schools which trained them as professional courtesans of the Temple of Delight, under the luminous eyes of the golden Aphrodite.

"My blood was hot wan wine of love, And my song's sound the sound thereof,

The sound of the delight of it."

The bar of the Hotel Lafayette is the only place in Havana where they mix tequila cocktails: tequila—the fiery sap of the Mexican cactus— Italian vermouth, lemon juice and sugar. It is as smooth as satin and as violent as lightning—what the late Mr. Huneker would have called "tiger's blood and honey." One should never dare drink more than two— or, at the most, three of them at one time—and one is better. The effect is mildly like that of heroin: a steady glow, a deep sustaining radiance, the godlike heightening of perception. It is a life-giving drink—and dangerous. In the interims, it is safer to stick to Bacardi—con un poco anis to give it the taste Parnassian. In the afternoons, a good drink is the mild, sweet mojito criollo: rum, vermouth, sugar, lemon and yerba buena. Or, drop in at the Baturro, a wine tavern whose walls are lined with rows and rows of bottles and barrels and kegs of all the wines in the world.

The revolution goes on, and the political situation seethes and bubbles with a tremendous hissing—and Americans read of the "Reign of Terror." Yet the life of the city beats on to the rumba cadence, and what slaughters there may be, are kept well hidden.

"Ay Mama Inés ... Ay Mama Inés ...

Todos los negros tomamos café ... Havana has been having revolutions since the beginning. They are a part of its articulation. But the more basic note continues throughout everything —news-hungry American journalists to the contrary—the fragrant, uxorious note of the city's blood. It is the geographical supplement to Swinburne—that luscious corruption of colour and music—the darkly burning exhaustion—the ceaseless presentation of a futile and yet fecund life, drenched in an effortless glamour.

Then I heard the song of the tropics, And my veins flowed veins, not blood,And I knew the sweet sickness of the south ...

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now