Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowDesperate Japan

PAUL HUTCHINSON

Industrialized, ambitious Japan, with a crowded population chafing under limits, explores a "manifest destiny"

Within two weeks after Comrade Maxim Litvinov lumbered to his feet to inform the League of Nations of the resumption of diplomatic relations between China and Russia, Kenzo Adachi, stormy petrel of Japanese politics, had completed the launching of a fascist party in Japan. At a convention attended by 3500 delegates the new movement— with uniforms, platform and pledges all complete—projected itself squarely into the center of far eastern politics. Thirty-three members of the imperial diet threw in their fortunes with Adachi at the outset; many more are confidently expected to follow. Japanese fascism must be reckoned with as a going concern.

The Occidental observer may find himself a hit confused by the platform of the new party. On the one hand it gestures in the direction of socialism—"controlled economy'' to end unemployment, increased taxes on wealth, lessened taxes on the masses. On the other hand it is in complete accord with the views of the army and navy—an end to cabinet government, a "Japanese Monroe Doctrine" for Asia, and a general clapping of the population into uniform. To the westerner such an attempt to combine socialism and chauvinism may look fantastic, foredoomed to failure. But in the peculiar circumstances now obtaining in Japan it is not fantastic. And it is certainly not foredoomed.

The West will understand the importance of the launching of this fascist movement in Japan, and the meaning of its strangely compounded platform, only if it looks behind the public antics of Mr. Adachi to the desperation of a nation that finds itself tricked by forces beyond its comprehension. A nation whose people are desperate is not concerned with logical politics. It is in no mood to spend time balancing the niceties of political philosophy. It wants action; immediate action; action designed to transform the conditions that are the apparent cause of the popular distress. Japan's new fascists sense this. Accordingly, they have drawn up a platform cleverly devised to appeal to the most harassed portions of Japanese society, added to it a series of slogans calculated to win military hacking, flung a new flag—an eagle flying against a golden sun!—to the breeze, and are now preparing to strike for control.

Why this spirit of desperation on which thev count?

With the Meiji restoration, Japan wholeheartedly accepted the gospel of modernization that had been preached to her by the west. She turned her back resolutely on the placidity, and the insularity, of her feudal centuries. She introduced all the paraphernalia of the western drive for a place in the sun of the industrial era. She planted her flag on foreign territory. She sent her ships into far ports. She linked her towns with rails of steel and she covered her cities with the pall of factory smoke. She gained power. She gained a seat in the conclaves of the great powers. She knew the thrill of empire. But she came to know something else also. What else?

Industrialization brought to Japan the great factories of Osaka, Kobe, Tokyo, and the bustling ports of Yokohama and Nagasaki. It brought, in time, the expansion of the empire to include the camphor supplies of Formosa, the oil of Saghalien, and more recently the coal and iron and wheat and soy beans of Manchuria. But it brought also overpopulation. It brought that hideous problem in the most acute form in which it has been experienced in any land. Within a half-century, a population that was about thirty million has become more than twice as large, while the official density rate is now given as 433 to the square mile. But even this does not tell the full story, since less than a fifth of the territory of Japan proper is available for cultivation! The recent rate of increase in population has been over 750.000 a year.

Seen in statistical terms this is bad enough. But seen in terms of the slums of Japan's factory cities, in terms of the pitiful little rice patches clinging on their terraces to the volcanic mountain sides, in terms of the fishing villages that never rest from their titanic struggle with the sea, Japan's over-population is unmitigated tragedy. What is to be done about it? Foster emigration, say some. That has been tried, under every conceivable impulse. In some quarters it has been thwarted by the nailing up of racial bars; elsewhere by the refusal of the Japanese themselves to go where they must compete with a lower standard of living. In all these decades since emigration has been encouraged, less than three million Japanese have settled outside the boundaries of Japan proper. Practice birth control, say others. Well, there are a good many Japanese who are doing that, and the movement in that direction will undoubtedly spread. But it will be a long time before birth control, in the villages and among the slums, can overtake that yearly population increase of three-quarters of a million hungry mouths. And in these days they are hungry!

Another thing that industrialization, the western magic, has brought Japan has been the bankruptcy of her farmers. Most Japanese, despite the excitement of life in the cities, still live on the farms. But they live there under a burden of debt that is appalling. Seventy per cent of all farm families are tenants, cultivating little holdings that average about an acre and a half each. Their rents are exorbitant—far above farm rental rates in Europe and the United States—yet the government piles on the taxes in terrifying fashion. Thus the figures which Dr. H. G. Moulton has collected show that in 1929 a farmer with an income of 100 yen a month had to pay a total of 270 yen in taxes! The most recent figures (Contemporary Japan, September 1932) show 31.36% of the total income of farmers in all groups going to the tax-collector! The budget passed in February, which is about twice as large as the one in force at the time when Dr. Moulton compiled his figures, will push the taxes up once more. And so large is the slice of their earnings taken by rural land proprietors that it is estimated that these tenant farmers are lucky if, after the incredible toil required by their type of farming, they have a net return equal to one-fifth that of the factory wage earner.

As the masses of Japanese have wratched themselves slipping into the squalor of the city slums or the hopelessness of rural bankruptcy, they have watched the new industrialism raise up a new order of millionaires. The misery of the workers has grown deeper with every year, but the power and ostentation of the big business interests have risen with Japan's star of empire. A whole new peerage has emerged, flaunting the glories of the Mitsui and Mitsubishi business houses in the place once reserved for Satsuma and Choshu clans. Year after year politicians have been exposed as involved in every imaginable form of graft—w ith the source of corruption always the vaults of the most impressive business interests. Those stoic qualities of personal life; those lofty ideals of public service which were the boast of the aristocracy of feudal Japan have been laughed into the discard by the narikins "who, lying back in pink upholstered foreign limousines, honk-honked common millions out of the narrow streets."

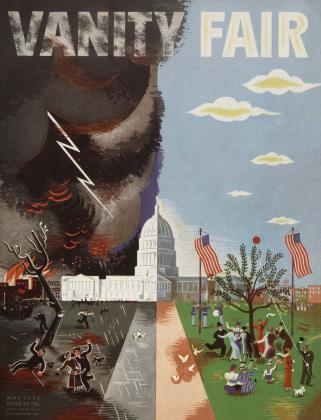

Again, the modernization which Japan has undergone at western encouragement has brought her fear and loneliness in a hostile world instead of the quiet peace that she knew in her old picture-book days. Japan still has her cherry blossoms, and the youngsters still play in the sunshine before the temples of Kyoto, as glad a sight as this world affords. But the modernized Japan finds this anything but a friendly world. Perhaps that is her fault. I think that, in large measure, it is. But that is not now the point. The point is that the individual Japanese feels that he and his nation are friendless in a hostile world.

They have plenty of reason to feel that way. They remember that, after they had fought the first war of their modern history, three of the powers of Europe combined to serve notice that they were not to be allowed to reap the reward of viclory. They cannot look to the east without seeing the exclusion bars of Canada and the United Slates, or to the south without seeing the "no trespassing" signs of Australia. China is hardly what might he called a friendly neighbor, even when no boycott is in effect. Russia has plainly shown her suspicion; despite the savage treatment accorded Borodin and other agents of Moscow only a few years ago Russia is already back on terms of friendly understanding with Nanking. And that understanding looks like a threat in Tokyo—as it is designed to do.

(Continued on page 66)

(Continued from page 24)

Nor has modernization been an unmixed blessing when judged by the cold values of yen and sen. True, it has brought an empire, with consequent commercial as well as political expansion. But it has brought, also, a national budget hopelessly out of balance; back-breaking taxes; a sadly depreciated currency; the loss of the vital Chinese market; the increasing withdrawal of foreign financing; unemployment on a vast scale. Nor is there prospect for any rapid improvement. On the contrary, the budget which the diet, after unexpected and significant opposition, has just passed gives impressive support to the contention of the Lytton commission that the adventure in Manchuria—far from having the economic advantages which have been contended—is a short-cut to national bankruptcy.

Is it not clear that such a convergence of catastrophes would be bound to produce despair? Here is a nation that has followed, with fanatical faithfulness, the course of "modernization" that it has been assured would make its position forever secure. It gains certain political victories. But it gains these at the cost of choking its land with mouths that cannot be filled, bringing its sturdiest citizens— the farmers—to poverty: filling its city streets with unemployed; thrusting its workers into slum-holes; surrounding itself with a ring of enmity and suspicion; raising the blatant and the corrupt to power, and finding itself at the end faced with economic ruin. What besides some unprecedented, some desperate action is to be expected ?

The military group was the first in Japan to believe that there was something wrong with the formula for national greatness which had led to the internal evils which were apparent by the opening of this decade. The proposals to which the big business interests and their politician-puppets had given support simply did not work out in more wealth, more comfort, or even less misery for the people as a whole. What could be done? The military answer was what might have been expected. Baron Tanaka foreshadowed it with his demand for a strong arm policy on the Asiatic mainland; the army brought it to fruition in Manchuria a year ago, and is still pushing it vigorously toward the Siberian frontier and over the border of Jehol. It is an attempt to compel national strength and prosperity at the point of a gun—just such an attempt as the European powers were making through most of the last two centuries.

Before the economic folly of this policy is condemned too vigorously, the thoughtful westerner will do well to try to look at it as a Japanese does. Here, for instance, is one of the bestknown of Japanese liberal journalists, Dr. Sakuzo Yoshino, professor of political science and one-time adviser to Yuan Shill-kai, writing on the army remedy for what Japan regards as the Chinese problem; "While the politicians for years pursued their ineffectual negotiations with a China increasingly contemptuous and hostile, the army in a few months established a situation in Manchuria which at least guarantees the effective maintenance of Japanese rights and interests."

Underlying every other reason, the sudden decision which the Japanese army staff reached more than a year ago to precipitate politics in the direction of bold action outside parliamentary control can be traced to one thing. This was resentment at and fear of the growth of Western pacifism. The Japanese army and navy has no belief in the good faith of this pacifism. It sees in the Covenant of the League, in the Nine-Power treaties, in the Kellogg-Briand pact only a trick of Western diplomacy, gullibly swallowed by Japanese politicians at the bidding of their business masters (who fatten on international trade), to "freeze" the map at the point where it now is—a world dominated by the whites. To give yellow aspirations a chance at the future, the militarists of Tokyo determined to smash the whole system of treaty restrictions to which civilian premiers such as Hara, Hamaguchi and Wakatsuki had agreed. The Manchurian adventure can thus be set down as, in essence, a product of army desperation.

But in the last two years, with the increasing difficulty of the economic situation, there has been evidence of the turning of still other groups toward some sort of direct action. First came the discovery of the rampant radicalism in student ranks. Behind that lay the inability of more than half of the graduates of universities and higher schools to find work. Then came the mutterings among the farmers, which have now reached so ominous a point that it is seriously proposed to devote an entire special session of the diet to agricultural relief measures. Then, as factory unemployment reached unparalleled heights, the manual workers showed their readiness for some sort of new method of action, with both the Sliakai Minshuto (Social Democratic) and Rono Taishuto (left-wing Labor) parties encouraging the first open declarations in favor of fascism. And now, last of all, even the extreme jingo groups, such as the Kokuryokai (Black Dragon) society, which have been violently anti-labor in the past, are ready to join.

The detailed proposals of the new party, as formally announced by Mr. Adachi, are obviously designed to act as a catch-all for as many disgruntled elements in the Japanese population as possible. The demand for a "controlled economy" in terms of government control of public utilities and shipping is meant to bring into line those who believe that the chief causes of trouble are the business interests— the Mitsubishi and Mitsui tycoons. The call for increased death taxes, income taxes, dividend taxes, profits taxes and taxes on the sales of large stores is an obvious "soak the rich" move. The promise to remit the land tax is a bid for farmer support; so is the promise to curtail local taxes. On the other hand, the declaration in favor of a "Japanese Monroe Doctrine" for Asia, for an end to cabinet government, and for rule by a small national council of state, supported by a drilled and disciplined popular army of black-shirts, is exactly the sort of thing for which the army and the organizations of super-patriots may be expected to shout "Banzai!"

(Continued on page 71)

(Continued from page 66)

It may be said that this fascist program has no more hope in it than had the liberal program of the old Minseito-Baron Shidehara days, or even the stop-gap program of the present Saito regime. Judged by the coldblooded standards of international finance, this is probably true. But a movement of this sort need not necessarily subject itself to any such standards of judgment. It is a product, as I have been trying to show, not of cool thinking, hut of popular desperation and anger. It seeks, as Dr. Yoshino puts it, to line up the majority of a people by "stressing discipline, the sacrifice of the individual to a common end, under the leadership of the competent few, as against the individualistic scramble of the modern capitalistic system in which the trickster, he he financier, manufacturer, or politician, invariably gets to the top." It is impossible to miss the growl of wrath beneath such words.

In some quarters there is a tendency to deny the importance of the formation of Adachi's fascist party, largely because Adachi leads it. There is reason for such skepticism. Adachi's record as time-server and opportunist does not make him seem impressive in the Mussolini role. But the prospect of a fascist uprising of some sort in Japan does not rest on Adachi's ambition. Once let the feeling of isolation. of friendlessness (now intensified by the action of the League and the international proclamation of the Stimson doctrine) fuse in the popular mind with the resentment against the rising costs of government, and the smashing of the cabinet-parliamentary system by a combined outbreak of the army and the farmers is next to inevitable.

A desperate nation, an angry nation, a nation ready to subject itself to great sacrifices to attain what it believes to be great ends, is not to he dealt with as nothing more than an economic entity, trying to sell and borrow in world markets, and reduced to helplessness if those markets are closed. Such a nation is like a trapped animal; it may be trapped, but it lias not lost its power to inflict terrible punishment on those who come near the pit into which it has fallen. Japan may be wrong in what she has done; I believe that she is. But she is desperate, and is not to be persuaded to any more reasonable course by a mere appeal to abstract legal, or even ethical, considerations. Unless her people can quickly be given genuine reason to hope that they will be dealt with by the rest of the world on a more generous basis, that solutions will he afforded those inescapable problems of housing, food and clothing within the order of international law. they will be almost certain to approve the fascist course of taking the law into their own hands, relying on the army, the navy, and a disciplined population to hew out the national destiny at whatever peril may he involved.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now