Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Colt-Adams Affair

How the Brother of the Famous Inventor Came to Murder an Unfortunate Printer

EDMUND PEARSON

R. ASA H. WHEELER was a teacher of penmanship and bookkeeping. A blameless gentleman, no doubt, but he first appears in history in the undignified act of peeping through a keyhole. And aided and abetted by one of his pupils,—a youth named Arzac Seignette.

The reasons were these: Mr. Wheeler's school was in a granite building at the corner of Chambers Street and Broadway, where Delmonico's was later to be situated. One chilly September afternoon in the year 1841—John Tyler being President of the United States, and peace generally prevailing in lower Broadway and City Hall Park —Mr. Wheeler was sitting in his school-room, quite as usual. His calm, and that of young Mr. Seignette, was suddenly broken by a curious noise in the next room. It sounded "like the clashing of foils"; afterwards there was a violent fall on the floor.

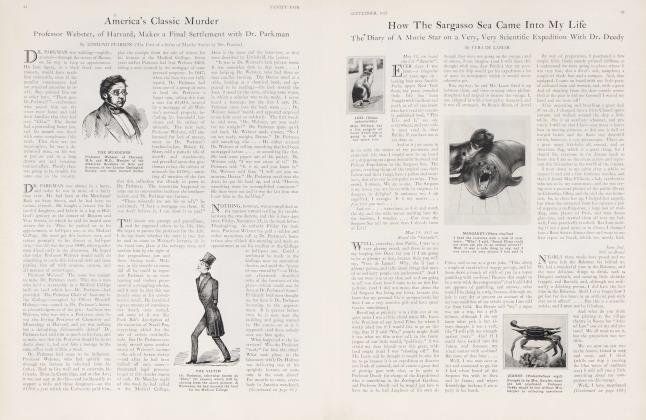

Aesthetic dancing had not yet come in, and Mr. Wheeler at once suspected serious trouble. His neighbour was another expert in bookkeeping: Mr. John C. Colt,— famous, until this moment, chiefly through his brother, Colonel Samuel Colt, who invented the revolver. The Colonel had his offices in the tower of the old New York University in Washington Square, but Mr. John pursued his profession—and argued about the rent, with his landlord,

Mr. Wheeler—in this building, at the corner of Chambers Street, so near City Hall.

Mr. Colt had written a manual on bookkeeping, and was in the agonies of getting it published. Mr. Wheeler probably knew this, and knew also something about the peevish temper of authors at such times. He went into the hall, and put his eye to the keyhole of Mr. Colt's door. The drop was down, but he poked at it with a quill pen, and pushed it aside. The teacher was then able to see a man, in his shirt-sleeves, bending over something, and apparently in the act of sawing. The limited possibilities of the keyhole prevented Mr. Wheeler from having a great shock: he was unable to see what it was on the floor which engaged the attention of the man in shirt-sleeves.

He and his pupil whispered and consulted, and took turns at the keyhole. Other pupils came, and were sent to fetch the owner of the building, or the janitor, or a police officer, They knocked at the door—somewhat timidly — and tried strategems to induce the occupant to open unto them. They were on watch, by turns, until the evening, but learned nothing of importance. The man inside evidently discovered the keyhole, for he blocked it up, so that that source of entertainment had gone.

Next morning, Mr. Wheeler borrowed a key and entered Mr. Colt's room. It was then empty. A large box, which had been noticeable, the afternoon before, was no longer there. The floor had been scrubbed, and was still damp. Oil and ink had been spilled here and there, and thrown in spots on the wall. Mr. Wheeler thought his dark thoughts —like Mr. Littlefield, janitor of the college where Professor Webster was to become so celebrated eight years later. But there was nothing to do but retire to his own quarters.

Half an hour later he had a call from Mr. Colt, who was very talkative. So talkative, in fact, that it was hard for Mr. Wheeler to get in his question: Mr. Colt, what noise was that in your room yesterday afternoon? The reply was: "You must be mistaken, as I was out all the afternoon."

A day or two afterwards, however, Colt admitted that he had upset a table, spilt some ink, knocked down some books, and made "a deuced mess". Later in the week Mr. Colt, "in a very friendly and urgent manner", invited Mr. Wheeler to come into his room, "to have some conversation on the subject of bookkeeping".

The invitation was repeated, but Mr. Wheeler declined, politely and resolutely, The celebrated wild horses, had any of them been available, would not have been sufficient to get the teacher into' Mr. Colt's rooms.

Four days after the disturbance, it became generally known in New York that one of the city's best printers was missing. Samuel Adams, whose place of business was at the corner of Ann and Gold Streets, had gone out to collect some bills, on the same Friday afternoon when Mr. Wheeler had been called to the keyhole. Since then, no one had been able to find him. One of his debtors was Colt, and the discovery of this fact had strengthened Mr. Wheeler's determination to engage in no private conferences in his neighbour's apartment,—no matter what alluring prospects might be held out of a little chat about bookkeeping.

A few more days passed, and Mr. Adam's family and friends were advertising and making anxious inquiries. The Mayor took a hand, and, with the police, interested himself in tracing the box which had vanished from Colt's room. Some drivers of carts gave information which led to the hold of the ship Kalamazoo, lying at the foot of Maiden Lane and taking on a cargo for New Orleans.

The hold was entered; barrels and crates were swung out. There was no difficulty in finding the box. It was opened, and the problem of the missing printer was solved.

The betting was general that it would be impossible to get a conviction against Colt, or to execute the sentence if he were condemned. He was too rich, men said; his family and friends were too wealthy and highly connected. He had still another brother who was a judge, in St. Louis.

However this may have been, Mr. Colt himself was in no condition of power or prosperity. He dwelt obscurely, with his mistress, Caroline Henshaw. His financial condition was precarious: the disputed rent with Wheeler had been ten or fifteen dollars and the debt to Mr. Adams was only about fifty.

When he was tried in the City Hall, in the following January, the State traced the progress of the victim's body from Colt's room to the hold of the Kalamazoo. Law Octon, the janitor of the building, a citizen of African ancestry, had seen Colt slide the box downstairs, the morning after the murder. If he had any suspicions at the time, he decided to be discreet. The driver of a wagon told of being employed by Mr. Colt to take the box to the ship. It was addressed to R. P. Gross of St. Louis, in the care of "Mr. Gray, New Orleans".

Who Mr. Gross may have been, for whom this charming surprise was prepared, I have not been able to learn. Had the box arrived at his address the situation would have anticipated that in two of Stevenson's stories: The Wrong Box and The New Arabian Nights.

Mr. Colt's brother, Colonel Samuel, appeared as a witness for the defence, and so did the beautiful Miss Henshaw. The statement that she was beautiful—with black eyes, and hair the colour of ripe corn—is made by a modern writer; a contemporary account merely says that "she presented an interesting appearance". Neither of these witnesses could aid him much.

Continued on page 80

Continued from page 60

The defence were forced to rely on the prisoner's own statement, read to the jury by one of his counsel. The killing of Adams was acknowledged, and the justification was self-defence. They had quarreled over the debt; the printer had accused the author of trying to cheat. Each called the other a liar, and a fight ensued. Adams was getting the best of it, and choking Colt, by twisting his "neck handkerchief". Colt seized a hammer and struck the other on the head. To his fright and horror, the blow was fatal. He did not dare confess; he lost his nerve and tried to conceal the crime.

This story was not well substantiated by the known facts, and was plainly disbelieved by the jury. They found him guilty of murder, and he was sentenced to death. All legal expedients were tried, but without effect. The other classic devices were attempted or planned: Colt was to escape from the Tombs in woman's clothes. This failed. His body was to be delivered to a doctor after hanging, and resuscitation was to be attempted. A favorite yarn, this; told about every notorious execution.

The day set for the hanging was one to give any newspaper man an apoplectic fit. Three or four sensations developed, in place of one. First, there was the marriage of Colt to Miss Henshaw. This took place in the cell at the Tombs. The Rev. Dr. Anthon, rector of St. Marks, and the prisoner's spiritual adviser, performed the service. Among those present was John Howard Payne, author of Home, Siveet Home, who was an acquaintance of the condemned man.

After the witnesses had gone and the bride had departed, Colt was left alone in his cell. Somebody had provided him with a knife, and with it he stabbed himself. He was found, an hour or two before the time of execution, lying dead upon his cot. Shortly afterwards, a fire broke out in the cupola of the Tombs. It did not amount to much, but happening, as it did, so soon after the suicide, it gave colour to the story that Colt had really escaped. The fire was part of the plot, said the romantics; the dead body was not Colt's; during the excitement, an escape had been contrived; and the influential murderer had cheated the law, after all.

It is probably as much a matter of fancy as the stories about the survival of John Wilkes Booth. Dr. Anthon testified as to the death of Colt, and under his supervision the body was buried in St. Marks. And the clergyman was neither a fool nor a rascal.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now