Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Death of Gulielma Sands

How a Sleigh Without Bells Figured in a Murder Trial Which United Some Famous Enemies

EDMUND PEARSON

ONE of the curious facts about a celebrated murder trial is that it may spring from an event so innocent or so obscure. All the public excitement; the rally of great lawyers and judges, may begin in surroundings as trifling and harmless as a children's birthday party.

A gardener's daughter goes to a rustic dance, and, on her way home, across the fields, falls into a pond, and is drowned. All the country, all the highest legal officials of the land, for years to come, are agitated over her fate, and a century thereafter men are writing learned books about the cause célèbre of Mary Ashford and Abraham Thornton.

Two brothers-in-law go into a garden, on July 4th, to amuse themselves at target practice. One is accidentally shot, and a year later their State rocks with excitement over the trial, for murder, of the survivor,—"a Harvard professor."

Some bandits kill a paymaster and another man in a little New England town, and by an unexpected succession of events, noted literary men, all over the world, become involved in a tremendous agitation. America, the happy hunting-ground of the murderer, the land in which the assassin habitually thumbs his nose at the law, and goes scot-free,—this paradise for the man of homicidal tastes, becomes an object of denunciation for "ruthless cruelty."

Janitors of American embassies, in far lands, have to jump for their lives, as bombs go off to express the brotherly feeling of those whose love for humanity is only equalled by their contempt for facts.

DID Miss Sands and her lover, young Mr. Weeks, leave the house together on a December night more than a century ago? If it was proved they did, there was no doubt what would happen to Mr. Weeks. Did he really take the bells off his brother's sleigh, so that he might drive it silently to a lonely spot in Lispenard's Meadows,—that dismal swamp on the outskirts of New York? If so, he would surely climb the gallows, in some public and convenient place, so that all the people could observe, and benefit by the spectacle. I do not think that they had begun to have hangings in Washington Square at that time,—it was too far in the country to make it convenient for the citizens.

It was a Sunday night, three days before Christmas, and the year was 1799. New York had probably heard the news of Washington's death, which had occurred a week earlier, at Mount Vernon. The city was to have, on the last day of the year, a great funeral procession, led by the commanding general of the army, Alexander Hamilton. Yet New York, which stretched from the Battery almost up to the ditch which is now Canal Street, was not too large to get thoroughly excited about the disappearance of a very pretty girl, named Gulielma Sands.

She was twenty-two years old, and although not herself one of the Friends, lived with her Quaker cousins, Elias, and Catherine King, in Greenwich Street, near Franklin. You may like to stand in that thoroughfare, under the shadow of the Elevated, and wonder where, in that neighbourhood, now so depressing, their pleasant cottage could have been situated.

The boarders at the Rings included a young carpenter, Levi Weeks, and his apprentice; two youths named Russel and Lacey; Hope Sands, the sister of Mrs. Ring; and others. Weeks had been paying particular attention to Miss Sands; to Gulielma—or Elma, as, for the sake of brevity, they called her. In fact, his courtship had given a household of active snoopers, listeners and eavesdroppers the time of their lives. Somebody, as was afterwards testified by the persons themselves, was forever taking off his or her boots, and pussyfooting up-stairs to apply an ear at the keyhole.

When, therefore, on the Sunday afternoon, Elma told Hope Sands and Mrs. Ring that she was going out with Levi Weeks that evening, for the purpose of getting married, neither of the ladies said a word about undue haste.

At eight o'clock—it was a cold night, with snow on the ground—Mrs. Ring had heard Elma come in, and now she heard her go out again. She had heard Weeks in the house, and thought she heard the two whispering together on the stairs. She thought that the young man went out with Elma, but she did not know. She did not see them together. All that she could say was that Weeks did come in about ten o'clock, pale and agitated, and asked for Hope and for Elma.

Neither was in. At breakfast, next morning, Elma was still absent, and although this was not unusual, the family began to inquire. A day or two later, a boy wandering near an unused well in Lispenard's Meadow, found a woman's muff. He took it home, but did nothing more. The funeral procession of the great ex-President occupied everybody's interest until New Year's.

On January 2nd, somebody looked down this Manhattan Well, as it was called, and discovered the body of Elma Sands. The well had been recently dug, but was covered and curbed. It was in a spot so lonely that tales about spirits and ghostly fires, hovering over the well-curb, soon had a wide acceptance.

If, like the writer, you are sufficiently curious about old murders, you may stand near the brink of that well, by going into a dirty little alley, near Number 89 Greene Street. The hole in the concrete pavement may not be the actual site of the well, but it is near it. And it is a fine exercise for your imagination to try to see this region as a deserted morass; an open field, where, in summer, the cows grazed all day long, and, at nightfall, took up their slow march, to the melancholy clanking of cow-bells, down that pleasant country lane called Broadway.

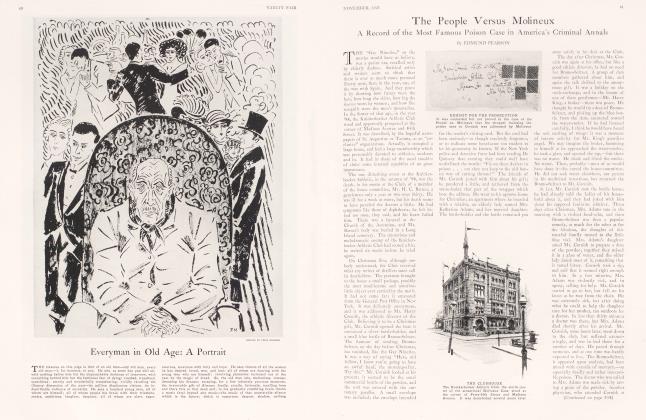

The trial of Levi Weeks, for murder, was held in the old City Hall, corner of Wall and Nassau Streets, where the Sub-Treasury stands. The Chief Justice, John Lansing, was on the Bench, assisted by Mayor Varick and the Recorder. The People were represented by an Assistant Attorney General, but even his redoubtable name, Cadwallader Colden, must have been hardly enough to sustain him against the heavy guns trained on him by the defense.

The brother of Levi Weeks was wealthy, and the prisoner was able to come into Court with the most distinguished array of counsel ever seen in a murder case. One was Brock-hoist Livingstone, but the other two were the great political rivals: Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr. Hamilton had already been Secretary of the Treasury, and Burr, within a year, was narrowly to miss the Presidency, and to become Vice-President instead.

THE session began on a Monday morning and continued until half-past one on Tuesday morning. The Chief Justice was for going on, but the jurors complained that they could not keep awake. There was a recess until ten on Tuesday morning, when the second and final session began and lasted until half-past two on Wednesday morning. Seventy-five witnesses had been examined, and the prosecuting attorney said that he had been without "repose" for forty-four hours, and that he was "sinking" under the fatigue. By mutual consent, closing addresses of counsel were omitted, and after a brief charge, the jury was given the case.

There are, in our records, feAV trials so dramatic. The 18th Century atmosphere, present in the ceremonious conduct of judge and counsel; and present also in the unruly behaviour of the croAvd, AVIIO wandered about and pressed close to the bar; the dark Court, lighted here and there by candles; the handsome and distinguished faces of the two statesmen; and the troop of witnesses —some of them Quakers, and some of them young rascals of the town— all these made the Weeks trial a strange event in our legal history.

(Continued on page 126)

(Continued from page 74)

The case against the prisoner was rather feeble. On that evening, nobody had seen him outside the house with the girl. About all that could he said was that she was cheerful and seemed in no mood for suicide. A woman's cries for help were heard coming from the vicinity of the well. A woman with two men in a sleigh, a sleigh without bells, was seen going toward Lispenard's. And Susanna Broad, "an aged and very infirm woman," testified that she heard a sleigh, without bells, come out of Levi's brother's yard about eight that night.

Prisoner's counsel, however, made Susanna's infirmities of mind quite apparent to the jury; she acknowledged that the incident might have happened a week before, or a week after Christmas. And one Demas Meed, who took care of that horse and sleigh, testified that there was no indication that they were out that night. The medical testimony was contradictory; some of the doctors thinking that the bruises on the body were not wounds, inflicted by another, but merely incidents of the girl's fall into the well. The famous Dr. Hosack, who testified for the State, only saw the body as it lay, strangely enough, exposed to public view for a whole day in the street.

The judge charged strongly in the prisoner's favour, and the jury acquitted him in four minutes. Public opinion was hostile, nevertheless, and he had to vanish from the city.

One of the oddest incidents in the trial was the appearance of a witness who gave testimony rather prejudicial to Weeks, and was accused of personal enmity. He admitted a quarrel with the prisoner about Elma; and it was alleged, by other witnesses, that he had been active in stirring up hostility to Weeks; that he had himself been near the well on the night of the murder; and that he had published handbills, directed against the prisoner; and describing ghostly figures which were to be seen around the well. This man, who flits in and out of the record of the trial, now as a witness, and now as a spectator, but always as a suspicious and malevolent figure, had the astonishingly apt name of Croucher.

Finally one William Dustan testified: "Last Friday morning, a man, I don't know his name, came into my store—"

Then occurs this note in the report: Here one of the prisoner's counsel held a candle close to Croucher's face, who stood among the crowd, and asked the witness if it were he, and he said it teas.

Apparently this is the foundation of the celebrated incident which has been amplified and repeated in the lives of both Burr and Hamilton, and has caused a controversy. Senator Lodge, who gives it in dramatic form in his life of Hamilton, later recanted, and attacked James Parton, the biographer of Burr, for telling it, in his book, about Burr. In both stories, the candles were used with great effect by the lawyer, to cast a sudden light on the face of a guilty man, and to lead the jury to notice his evil looks.

As it is apparent that Parton got the story on good authority, directly from a friend of Burr, who had heard the latter relate it, Senator Lodge's attack seems unnecessary. Nor is it clear that the incident was trifling, as the Senator concluded, for even these few lines, following Croucher's earlier appearances in the trial, indicate that the moment was a striking one in that midnight session of the Court.

Croucher is said to have ended his days on the gallows. Another and more eminent figure, the Chief Justice, was the victim of a mysterious fate, but the story deserves a longer treatment than is now possible. To illustrate the great amount of legend, and the atmosphere of doom which surrounded the trial of Levi Weeks, there may be quoted a remark said to have been made by the Quakeress, Catherine Ring, as she heard the verdict. In her opinion, the betrayer and murderer of her poor, young cousin was escaping from all punishment. Turning to his chief counsel, Alexander Hamilton, she said, with great solemnity:

"If thee dies a natural death, I shall think there is no justice in Heaven! "

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now