Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Nowhigh life and livers in the reign of edward VII

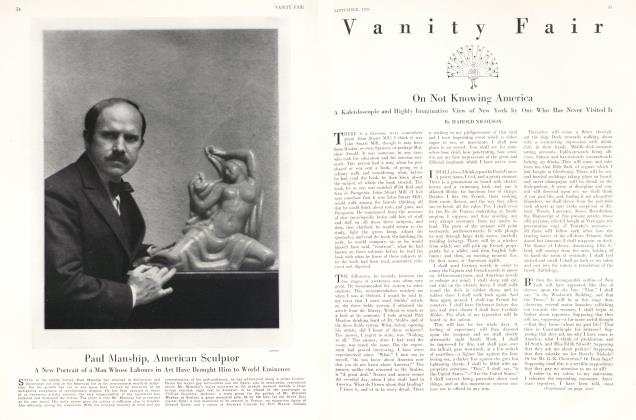

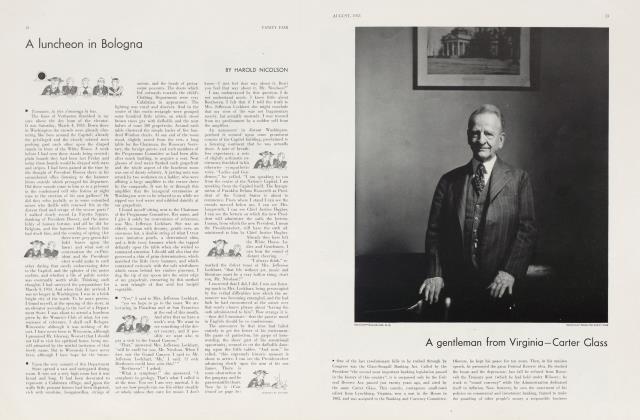

HAROLD NICOLSON

a circumstantial rendering of the plush delicatessen of a swell Sunday in the time of europe's first gentleman

■ The age of Edward VII will, we may presume, live in history as an age of comfort.

It was not. It was an age of fevered luxury; and at the same time it was an age of peculiar human ineptitude. People in those Edwardian days possessed false values and they endeavoured, fortunately without success, to impose these values upon their children. The whole glittering decade—the first decade of our century—passed in an atmosphere of plethoric friction. It is time that the jade and lobster of the Edwardian epoch were exposed.

In the first place, people ate excessively, and competitively. No age since that of Nero can show such unlimited addiction to food.

A man, under King Edward, was called by his valet at eight thirty. Valets then were silent but hostile men who would arrive bearing in their left hand a neat brass can of shaving water, and in their right hand a neat brass tray of tea, toast, and Marie biscuits. The Edwardian—his blinking, plethoric eyes above his pink silk eiderdown—would munch the biscuits and sip the tea. He would then adjust his teeth, adjust his hair, adjust his Afghan dressing robe, and slouch, plethoric, along the passage to the bathroom. If he were staying from Saturday to Monday in a rich house (and all houses in the Edwardian epoch were rich), he would find in the bathroom the scented smell of his predecessor's indulgence (flacons was the word they used) which contained the Hamam Bouquet of Mr. Penthalicon. The guest would pour this unguent into the bath from which his valet would already have removed the stains, the soap-suds and the other disjecta membra of the former occupant. The water would be tepid. Edwardian water was always tepid. His predecessor had left his signet ring in the soap-dish. Through the smell of Hamam Bouquet would gradually pierce the smell of lavender bags and Sanatas. Disgusted and dyspeptic, the Edwardian would proceed with his bath. He shaved in it.

■ When he returned to his bedroom, along the red pile carpet which marked the unending symmetry of the corridor, he would find that the windows had been slightly opened, and that his clothes had been laid ready for him upon the chintz settee. Taking a Regie cigarette from his Faberge case he would contemplate these clothes with satisfaction. If he were a good Edwardian his shirt and collar would be all in one. A white shirt, somewhat frilled and tucked on the breast, ended in a stiff little upturned collar. Hard, expectant, circular,—that collar would shortly encase his neck. Alternatively a Piccadilly collar of equal rigidity would be waiting for him on the dressing table. Black clothes: a grey silk tie; a neat turquoise pin representing a pheasant walking slowly from left to right; a white cambric handkerchief; a dab of eaude-cologne; his purse; his card case; the smell of Euchrisma as he brushed his hair. Then he descended, down red pile staircases, to breakfast.

■ Only the really improper Edwardians had breakfast in their rooms. The others met,on that Sunday morning, in the dining room. The smell of last night's port had given place to the smell of this morning's spirits of wine. Rows of little spirit lamps warmed rows of large silver dishes. On a table to the right, between the windows, were grouped Hams, Tongues, Galantines, Cold Grouse, ditto Pheasant, ditto Partridge, ditto Ptarmigan. No Edwardian meal was complete without Ptarmigan. Hot or cold. Just Ptarmigan. There would also be a little delicate rectangle of pressed beef from the shop of M. Benoist. On a further table, to the left, between the doors, stood fruits of different calibre, jugs of cold water and jugs of lemonade. A fourth table contained the porridge utensils. A fifth, coffee, and pots of Indian and China tea. The latter were differentiated from each other by little ribbons of yellow (indicating China) and red (indicating, without arrière pensee, our Indian Empire). The centre table, which was prepared for twenty-three people, would be bright with Malmaisons and toast-racks. No newspapers were, at that stage, allowed.

The atmosphere of the Edwardian dining room at nine thirty was essentially daring. A pleasant sense of confederacy and sin hung above the smell of spirit lamps. For, had they not all been brought up to attend family prayers? And had they not all eluded that obligation? It was true, of course, that the host and hostess, with their niece, had (at nine) proceeded to the family chapel and heard the butler reading a short collect for the day. But the guests had for their part evaded these Victorian obligations. This corporate evasion gave to the proceedings an atmosphere of dash. There was no insincerity in the bright gaiety with which they greeted each other, with which they discussed how he or she had slept. "A little kedgeree, Lady Maude," "Oh, thank you, Mr. Stapleton."

Evidently it was all going very well. Edwardian breakfasts were in no sense a hurried proceeding. The porridge was disposed of negligently, people walking about and watching the rain descend upon the Italian garden. Then would come whiting and omelette and devilled kidneys and little fishy messes in shells. And then tongue and ham and a slice of ptarmigan. And then scones and honey and marmalade. And then a little melon, and a nectarine or two, and just one or two of those delicious raspberries. The men, at that stage, would drift (I employ the accepted term) to the smoking room. The women would idle in the saloon watching the rain descend upon the Italian garden. It was then ten thirty.

If the house possessed no private chapel the guests would then "assemble in the hall". There would be footmen fussing about in cockaded top-hats and long buff overcoats with gold buttons. A degree of jollity would be extracted from the process of deciding who would drive to church in the wagonette, who in the landau, who in the victoria, who in the brougham. And who should walk. The latter category seized umbrellas and capes. People jingled off, clasping their prayer-books and the half-crown for the offertory. From the side door the children, wide-eyed and washed, would appear with their governesses. They crossed the park to the church beyond the lodge.

■ With fervour would these Edwardians sing the psalms and the hymns, with reverence would they listen to the stories from the Old Testament. The smell of leather and wet mackintosh would permeate the damp little church. Every now and then an umbrella would tumble from a pew. The final benediction descended upon rows of bowed heads. The ladies' hats were rich with artificial flowers; the heads of the men were rich with the smell of Euchrisma. They walked back to luncheon under dripping trees.

The half hour before luncheon hung a little heavy on their hands. The women would repair to their rooms and deal with their hair and faces. The men would gather in the library where they would shortly be joined by the curate or, as the case might be, the house chaplain. A shy little man this, not knowing all these London people, not very certain how to modulate his voice. The younger men would come in later, having changed into tweeds. There were silver vases of white roses, and cut glass vases in which the roses were red. The hostess, passing from group to group, would flick irritable emerald-laden fingers at these flowers, tugging them into different shapes. They would pass in to luncheon. The curate, hanging behind, would hang behind.

■ Edwardian luncheons were strained and bright. There was a theory that the good hostess should "draw her guests into conversation". This entailed a process of flinging conversational flies across the vast table and not waiting to see if the fish rose. "Colonel Westmacott, you simply must tell us about the Zambesi" and "Oh, Clara! Is it really true that dearest Evie has got to go to Nauheim?" There was a buzz of general talk. It would only be a buzz.

After luncheon they walked round the park. They did not visit the stables. Since the introduction of motors, the stables had become Victorian. The elder members of the party would drive over to Stonehenge in an open Daimler. They appeared, aged and flustered, in motoring veils of watered silk. Colonel Westmacott, in a tweed cape and spats, stumped off with Lady Moira to visit the quarries. Captain Fairfax took Miss Sinclair for a drive in his de Dion. Professor Steinholtz slept.

Tea was served in the blue gallery. There were little ginger biscuits which one could only get from Biarritz and of which one kept a store in case the King came. All Edwardian houses kept stores of things like ginger biscuits and aubergines and French patisseries and bath salts in case the King came. And he did come. He came over and over again. And on Monday morning other people would read all about it in the Morning Post. It was only, however, when the King actually did come that one went so far as to have lobster salad for tea. Otherwise one just had scones, and egg sandwiches, and pate sandwiches, and cucumber sandwiches, and chocolate cake, and walnut cake, and coffee cake—and cake. Also there were little plates with china-handled knives to match, from which people ate Tiptree jam with toast or brioches. The butler, the groom of the chambers, the under-butler, and the footmen would move about offering food. But in the best houses (and most Edwardian houses were the best) the servants did not remain for tea.

■ After tea there would be bridge tables in the red drawing room, and the men would not infrequently play billiards. Dinner was at half past eight. The women would return an hour before to change their tea gowns for the other things which they donned to dine. The men would also change into clothes even more galling and restrictive than those they had worn all day. The guests would reassemble in the yellow saloon.

■ The host by this time was already bored by his party and would indicate, a little irritably, who was to take in whom. He held a fussy little piece of paper in his hand and would fuss from one man to another. The women, one by one, entered the room slowly, showing off their clothes. Then there would be dinner. Ptarmigan and champagne. Champagne and ptarmigan. The hostess did not endeavour to stimulate general conversation at dinner. One only did that at luncheon. At dinner people talked, inclining their neat bodies, sideways, at their neighbours. At nine forty-five the women swept, with backyard glances, from the room. The host would take his glass of port, holding it with gingerly fingers from above, and move to the seat vacated by his wife. At ten-fifteen they joined the ladies in the music gallery.

Bridge again. And at midnight, in the Holbein room, there would be devilled chicken, and more sandwiches, and every form of spirit and mineral water which man or woman could desire. In the corridor upstairs the ladies'-maids would hang, listlessly yawning. Fires would sparkle in the grates, reflected in brass bedstead and in mirror. The pink silk reading lamps were lit beside the beds. Upon the night table stood bottles of Malvern Water and of Vichy, and covered dishes of sandwiches. A ribboned coverlet of swansdown would be draped across the sofa. The kettle, by the fire-place, purred.

Next morning the gentlemen were awakened. Their valets would pack their Enos and their shooting sticks. They would return by train to London. Their carriages would meet them, horses champing bits, at the arrival platform of Paddington. In the train, coming up to London, the members of the house party would read, in the Morning Post, a list of the members of the house party. They returned to Curzon Street feeling very pleased indeed. And, next Saturday, it would all begin again.

(Continued on page 114)

(Continued from page 73)

Compared to the strenuous social discipline which these hardy people imposed upon themselves, our own laxity may seem a little decadent. Who among us today would really dress for church and dress for luncheon and dress for tea and dress again for dinner? Who among us would possess the endurance to relish all those meals, to relish all that tittle tattle? Who, today, would care whether he was or was not invited to Upyatt Lacy or to West Warren? Who, today, prints or reads those lists of Saturday to Monday parties?

The war has not been fought in vain. We have been released from false pretensions. We have our jumpers, our cocktails and our freedom. We can smoke pipes in Bond Street, and wear grey flannels in June.

I do not regret that I was old enough to touch the fringe of Edwardian luxury. But I render thanks to Providence that I was also young enough to relish and share the wider liberties of our subsequent age. Let us be frank about it. The Edwardians weje vulgar to a degree. They lacked style. They possessed only the hard glitter of their own electric light: a light which beat down pitilessly upon courtier, ptarmigan, bridge scores, little enamel boxes, and plates and plates of food. They lacked simplicity, and their intricacies were expensive but futile. I for one prefer the wide circle of our simpler horizon.

Nor, when all is said and done, can one forgive the Edwardians for their fundamental illusion. For it never dawned upon them that intelligence was of any value.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now