Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

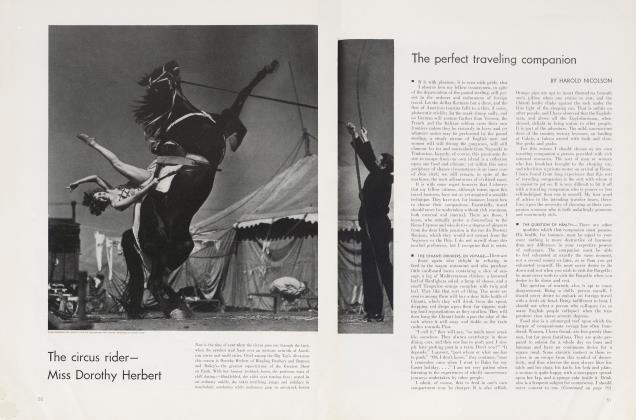

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWhat struck me most in America

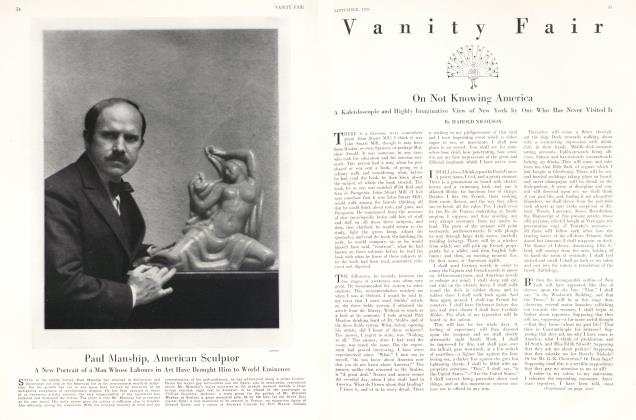

HAROLD NICOLSON

I am afflicted, and perhaps unduly, by an ironical turn of mind. It is not, I venture to hope, that I am less benevolent than the average, but rather that my attention is arrested more readily by the distortion of objects than by their normality. I am apt, that is, to see things a trifle obliquely, and this astigmatism is not ocular merely, but also mental. The incongruous therefore appeals to me more directly than does the congruous. I find, for instance, that I can express derision more easily than I can express respect, that it is more difficult for me to adopt the vocabulary of admiration than to slide into the verbiage of misprisal. I regret this circumstance, knowing well that it is a symptom of the third-rate. Yet 1 contend that to make fun of life, to mock at oneself and at one's friends, is an attitude not wholly inconsistent with kindliness; and that one may feel gratitude even though the expression of that gratitude stumbles haltingly upon the barrier of one's teeth. 1 am profoundly grateful to America for many things: for generous hospitality, for many (I trust) enduring friendships. for experiences of great beauty, and for countless lessons regarding democracy, cleanliness, organisation, orange-juice, and uplift which I shall not readily forget. Yet when I come to write of America, the old facile frivolity assails me, and 1 find myself saying things which may (for the Americans have one skin less than the Europeans, and wince at a tickle) cause offence.

Yet there is one point on which I can express myself with serious enthusiasm; there is one question which evokes upon my face, not the accustomed twist of mockery, but a wistful, slightly downward look—a look which (though 1 say it as shouldn't) is beautiful in its way, and in its way Contemplative. "What" so runs the question, "struck you most in America?" It is then that I put on that slightly downward look. "Well," I answer, "it was their instinct for equality." "How do you mean exactly?" they will ask me. And then I expand my soulful theme as follows.

I begin with a story. It is not a very good story, but it seems to me both illustrative and picturesque. I was staying last March on a ranch in the Californian desert. I slept in a cottage on the Warm sand. The cottage contained a bedroom, a sitting room, two shower-baths, a huge bowl of fresh oranges, and a faint desert lily in a vase. One had one's meals in the main building with the other guests, our host and his wife. There were clean deal tables in the dining-room and two maids, called Martha and Helen, handed wide dishes of asparagus across our shoulders. A loud bell would ring when food was ready and I would walk across from my cottage, through drifts of purple verbena and the desert primrose. At night one would not see the verbena, but the primroses would glimmer faintly and the smoke trees would rise suddenly in the moonlight, soft and sudden as the mist above some tropical marsh. Above and behind me were the dry, silent mountains, above and around me were dry, silent stars, and when the little moon climbed slowly the greater stars refused to be dimmed. There was also a large water tower with a light on it. And to the south stretched the desert and the road which runs past the salt lake and on to Arizona.

One night we took our supper along the road and lit a fire under a red rock. There were some twelve of us, including our host and hostess, and we sat round the fire waiting for the lorry to arrive with food. We threw dry sage upon the flames and the smoke twirled up against the red rock in gusts of incense. Then the lorry arrived and we sat on benches at a trestle table, and Martha and Helen handed wide dishes of asparagus across our shoulders, and the men from the ranch grilled steak in a little hollowed fire of their own. When it was all over we gathered again under the red rock and our camp fire crackled angrily to the dried branches with which we heaped it. A cowboy climbed to a ledge of the rock with a banjo and sang to us. He sang Out on that Utah trail and he sang another song about Snore on Doggy which be explained was a lullaby addressed to young cows. Then he picked up his banjo and walked off into the night. By that time Martha and Helen had cleared the table and the other ranch hands had packed it and the pots and kettles back into the lorry. We remained by the fire-side, where Martha and Helen joined us, together with young Bob, who looked after the horses at the ranch.

It is here, after much delay, that I reach the point of my story. Martha was asked to sing to us. She sang some Scotch tunes which she had learnt from her mother. Then Bob sang ol' Man River. It was at that moment that I realised that America was something wholly different from Europe.

I reasoned as follows. Supposing that this picnic were taking place not in the Californian desert but in some clearing of the Kentish Weald. It would be quite possible that the two parlour maids and the groom would be invited to join us around the fire. It would not be impossible that they should be asked to sing. But what would be wholly impossible would be that both the masters and the servants should treat this invitation as a matter of course. Inevitably—if only in slightly forced note of considerateness—there would on the part of the masters have been a hint of condescension. Inevitably—if only in a momentary blush and giggle—there would on the part of the servants have been a suggestion of embarrassment.

Yet Martha, as she sat beside me, sang out clearly into the night—and the surrounding mountains, as they gave back to us her plaintive cry, gave back no tone of self-consciousness, no note of the embarrassed. There she sat, her arms folded across her knees, singing Loch Lomond as if in the circle of her own family, nor did she giggle when the song was done. Bob also, opposite to me with the flames flickering across his face, displayed no gawky hesitation when pressed for 01' Man River. He explained that he did not remember all the words but that he would hum the bits which he had forgotten. Amused and simple he sat there, opening his young mouth wide to the firelight, singing that song which holds so much of the mystery and pathos of America

I confess that I was impressed by this exhibition. There was of course that Walt Whitman feeling about the boy singing there with his young shadow flickering behind him upon the scarlet rock. There was of course the effect of the surrounding silence, of the still, dry mountains in the dark. I am not impervious to such romantic associations. Yet my dominant impression was one of self-criticism. I felt that in contrast to such simplicity the genteel snobbishness of Europe was an arid and inhuman thing. I felt that this outright assumption of equality might remain perhaps the most intense of the many lessons which America had taught me. I was right in so feeling. The lesson has remained.

I should define this American discovery as that of the distinction between service and servitude. On first reaching the United States I had been somewhat irritated by the ubiquity of that word "service," feeling that it was overdone and commercialised, feeling that it represented a fraudulent verbal excuse for the inevitable inequalities of a capitalistic system. The flickering, fire-lit, self-assurance of Bob and Martha dispelled this suspicion. It convinced me that this very "service" was the most original, and perhaps the most enduring, constituent of the American Idea. Thereafter all sorts of other apparent incongruities fitted into the same natural pattern.

Continued on page 54

(Continued from page 16)

I had heard much of American hospitality. I found it even more lavish in depression than it had been in the time of the Big Bull market. I had heard much of American kindliness. I found it more constant and more widespread than I had ever supposed. Yet after that night beside the camp fire 1 came to realise that this hospitality, this kindliness, were both symptoms of something far more essential. I realised that they were symptoms of an instinctive sense of equality manifesting itself in spontaneous helpfulness. And this realisation, as 1 have said, is the most important thing which I have brought back with me.

One finds it in many ways. At San Francisco the editor of a leading paper sacrificed the whole of one valuable afternoon in order to show me the Aquarium. In Europe, a man of similar occupation and civility would have confined himself to lending his car. At Atlanta one afternoon, a man of whom I asked the way, turned back with me and sacrificed a full half hour in order to assist me. At Charleston a woman motored some hundred miles in order to enable me to catch a more convenient train. At Cincinnati a redcap, distressed because I had missed a connection, gathered his fellow redcaps round me in order to create a chorus of sympathy. "Well isn't that just too bad!"—and I was comforted. Such actions proceed from something more than courtesy, from something more than kindliness; they proceed from a sense of human duty. It is a sense which in Europe has become a trifle tarnished.

After such an experience the surface servility which one finds in England strikes a jarring note. "This way, Sir, please" may sound more deferential than "Come this way, folks"—yet one does not care for deference. There is a companionable quality in American helpfulness which is far more satisfying than the sugared though sulky acquiescence of the British brand. In rural districts at home the relations between servant and master are still upon a looting of sincerity: in urban districts there is always a sense of unreality, a hint of a sneer behind their smile. The exhilaration with which America fills one is not due solely to the ringing climate. It is due also to the fart that here at last one is rid of class distinctions, that here at last the foetid vapours of class-consciousness have dissolved in the sun

(Continued on page 60)

(Continued from page 54)

On my last day in New York I was obliged to visit the Customs to obtain my sailing permit. I walked along endless corridors and was directed to a door marked "Alien Sailing Permits." One is always a trifle wounded by the term "alien" and especially in a country where one feels so much at home. It was therefore with a sense of having been slightly offended that I pushed the door and advanced to a large counter which separated the end of the huge room from the remaining portions where clerks worked at separate desks. There was a small old man behind the counter to whom I disclosed the purpose of my visit. "Now don't you worry," he said. "Just you come along with me." I was not worrying in the least, yet his protective manner wiped from my soul the stain of that word "alien." He opened a flap in the counter and motioned me to come inside. He then put his arm upon my shoulder and piloted me gently to the appropriate desk, lie was a small man and had to stretch high to place his arm upon my shoulder, yet I liked the feel of it. Very gently he led me to a distant table and brought a chair for me on which I might sit down while my papers were being examined. His attitude was that of a sick-nurse in some clinic who leads a nervous patient to tile operating table. "Now don't you worry," he repeated. And when, in a few minutes, I had obtained my papers, with the same paternal, the same sick-nurse, gesture, he piloted me back. "I am very much obliged to you," I said on leaving. "You're welcome, sure," he answered— that lovely phrase which to me echoes all that I most love about America.

Would it have been possible in Europe to enter into just that sort of relation with a Customs Official? No— it would not have been possible. One might, with great good fortune, have met with courtesy. But it would have been a class-courtesy and not a human courtesy. I should not have emerged into the April sunshine with so warm a feeling inside.

This, therefore, is what has struck me most. Egalitarianism in America is not, as so often in Europe, an acid, envious and destructive frame of mind. It is a sweet, generous, constructive frame of mind. To have learnt that lesson is a rich recompense for thirty thousand miles of travel.

There! I have actually written an article which is not disagreeable.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now