Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe screen

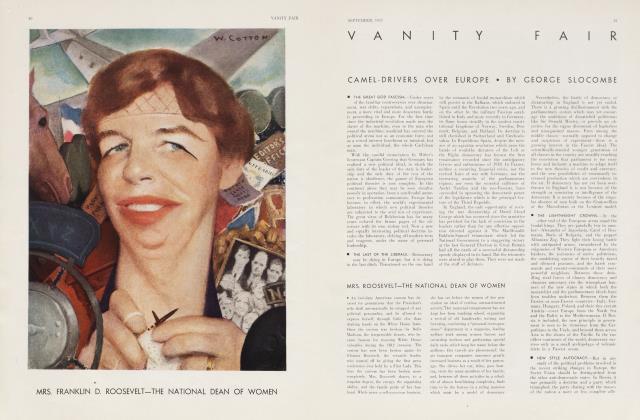

PARE LORENTZ

A statue steals the honors from Marlene Dietrich in her new film—not quite the worst of the summer's crop

■ HOT CLAY.—Mr. Rouben Mamoulian

opened the new movie season by presenting Marlene Dietrich in petticoats instead of pants, and if his Song of Songs is indicative of the major pictures we are to see this year, then the season has been shot in the hack and dropped dead in its tracks.

I have three objections to Mr. Mamoulian's production: it is pretentious Schnitzler nonsense, unrelieved by one note of gaiety or humor; it is handled in a heroic manner, yet the fall and rise of Lily, the virgin artist's model, at no time gathers any dramatic force (the presence of Miss Dietrich per se is. presumably, so important one need not wish in vain for a variation of the ancient movie formula of the girl who goes to the gutter and back for love) ; and, objection number three (although he is well cast) is Lionel Atwill, the last—please—of the great hams.

■ I see no excuse for the dreary quality of the picture. The monkey-shines under the apple blossoms were supposed, no doubt, to create an atmosphere of child-like innocence, and so they might have, if each scene did not always conclude with a close-up of Miss Dietrich's dead pan—veiled by false eye-lashes that scrape her chin every-time she blinks— registering faint surprise at the whole business; and the prosaic chanting of the erotic Old Testament poem might have brought some of the intended fire to the show, if Miss Dietrich's basso-profundo had sounded a little less like a station-master calling off trains.

But Samuel Hoffenstein's manuscript would not have stood any strain no matter who played it. There is no humor, no fun in the thing, except what little you can extract from the stock character of a drunken old shrew (neatly played by Alison Skipworth). And Mamoulian belies his good record by winding up the picture with an old-fashioned, queazy, all-is-forgiven-come-home-Mabel scene.

Saving the grinding boredom of the picture is the photographic quality which only those few directors who know what they are about can put in a movie. There are no superfluous, laborious narrative scenes in The Song of Songs; its people are set in a genuine movie world of nonesuch. There is a fine atmospheric quality to the picture that is tight and consistent, and there is more music underlying the story than you may realize, hut, even so, it is disappointing; after Love Me Tonight, 1 cannot understand how Mamoulian could have been so careless and allowed his staff to put such an irrelevant and insignificant score in his movie.

The director, of course, has done his duty by his employers and their imported passion flower. He has made what should be a successful picture by surrounding Miss Dietrich with lovely pictures, and, also, by an adroit trick which may lead to a disturbing, if interesting, development in movie-making.

Realizing the frigid qualities of his leading lady, Mamoulian went his colleague, Mr. Sternberg, one better. Where Miss Dietrich's official director used to use fine lighting and musical effects to make his heroine important, Mamoulian puts his Theatre Guild symbolic tom-foolery to good purpose in The Song of Songs. Throughout the love scenes, he cuts his picture directly from Miss Dietrich's pale stare to the statue which her lover is modeling. As he gets along with this business, the nude finally emerges rather flatteringly, one would say—and Brian Aherne begins to make serious love to the full-figured statue; good directing makes it a very effective trick. The camera flashes from the silhouette of the heroine to the full-length nude so aptly that the nude becomes pretty alive; and Brian Aherne gets much freer with his clay Dietrich than, up to now, the police have permitted live actors to be.

It is possible that the use of nude figures to interpret such scenes might lead to some interesting pictures; where the actress can be surpassed in warmth by a journeyman's piece of sculpturing, it at least furnishes a simple standard for measuring ability.

■ THE RUNNERS-UP.—One can understand the confused state of the daily press, as it sunk almost to a man under a great wave of enthusiasm for The Song of Songs, when you consider the stuff they have been dealing with during the tail-end of the 1933 season. Good pictures and directorial skill came as a blessing, regardless of the story or the cast, when you consider that for days they have seen things like Midnight Mary, in which a chippy gets in a prison, does a Maedchen in Uniform, and then gets her man; Disgraced, in which a girl goes to jail and then jumps out into the arms of her man; or Hold Your Man, in which a lady of leisure -goes to jail for her man. and, in this one, is married to him there in order that her b-a-b-y may have a name.

Or, to continue the list, if it hasn't been the prison motif, they have had to consider the academic qualities of a picture called Captured, in which a husband discovers that his best friend has been mooning after his wife, whereupon he goes out and gets himself killed; also, a novel hit of drama called Storm at Daybreak, in which a husband discovers that his oldest friend has been scraping and bowing before his wife, whereupon he goes out and kills himself. There was, I must admit, some novelty to Captured; after the death of the accommodating husband there was not a fade-out showing the lovers embracing at the grave of the deceased.

With the slightest restraint, there might have been something in Captured. Two British flying officers are interned in a German prison camp; the commanding officer of the prisoners has persuaded the Germans to let the men work in order to keep up their morale and health; the condition being that, if one man tries to escape, they all go hack to bread and water and the dungeon.

■ RAPE AND ESCAPE.—The officer is married: his best friend, also in camp, won the wife's affection while the husband was fiddling around at the front. The wife keeps sending tender messages to her paramour; this gets on the fellow's nerves so that he decides to escape, thus letting down his comrades. On the night he does, one of the men rapes and kills a German girl. Under international law the escaped man must be returned for court martial. The husband (done vaguely by Leslie Howard) meantime learns two things: that his friend has betrayed him, hut that he is not guilty of the rape and death of the peasant girl. 1 have gone into this little story completely because it had some possibilities: alas, the Warner Brothers put them on ice quickly.

The prison camp looks like the backstage of the Metropolitan Opera House after a performance of Tristan it is patently a stage setting, although there was the whole of California to work with. The husband's affection for his wife is endlessly dealt upon; there were no details, no story variations in the plot for at least twenty minutes.

However, once they had mightily established the fact that the husband liked his wife, it was idiotic to have him sacrifice himself for a man who had betrayed him, as well as the entire prison camp; furthermore, even if they had to make this foolish compromise with a possible box of ice figures, they need not have put on an escape that looked like Den liar, in which five hundred men run across a field and find two hundred German bombing planes-—conveniently warming up. although unoccupied. Maybe I'm wrong about the whole thing—perhaps it was so botched I just thought there must have been some reason for the production in the first place.

There is quite a hit of charm to Storm at Daybreak; not, one imagines, so much as the Hungarian play originally had, hut because it has some form and some flavour left to it, a deal more than you'll find in the quickies hitherto mentioned. I don t believe you could assemble a dozen Hollywood juveniles and make them appear natural and gay. hut the director put his production in pretty wrappers, and his characters in pleasant pictures, and tones down the labored antics of the extras.

Kay Francis is always heavy-handed and lethargic in her work, but in such a production as Storm at Daybreak, she has some authority and an ability to—as the phrase has it—wear her clothes well (meaning that, unlike Crawford, Garbo and Dietrich, she doesn't always look as though she had just come from a drunken fancy dress ball). Nils Asther, who is the husband's fortunate friend in this one, is a fancy left-over from the silent era, in which movie actors had to do all their work with their hands, feet and teeth, and he is still working bravely at the old trade.

Continued on following page

Walter Huston gives a fine performance in the one well-written part in the picture; there is some dramatic logic in his death, and. while there is little body to the picture, except for the unimportant details up to the fore-ordained death of the husband, those details have some grace and sense in them, which— the class will please repeat after me is more than you'll find in other hot-weather movies.

■ NOTES ON BAD HABITS.—The movie is such a personal medium, one begins to notice changes in actors, personalities and figures with the same intimate attention you give to the gradual appearance of your wife's double chin. Watching Leslie Howard in Captured, I could not but feel sorry for the fellow, even though he doesn't have to do it. You can see his talent wasting away before your eyes. In a part which would not stand playing, he has to say words which mean nothing; he has to try to bring life to dramatic scenes which patently were thrown together between frenzied conferences by fellows who couldn't write a simple dramatic speech, even if them cared to. Being a shrewd actor, Howard doesn't blow the part down; he reads his lines as simply as possible and lets them go at that. You can't work in a thing like Captured. What, however, happens to an actor or actress who loafs before the camera for a year or two? How can they go from such enervating work, drop all their bad habits, and step before a camera or on the stage and take hold of a full-grown part with any surety, without showing their indolent movie habits?

The majority of actors can't tell from the manuscript whether Shakespeare or Mae West wrote the thing, but, even so, they unconsciously must take on some of the habits they get from their dreary assignments. And I think it is the best of them who suffer declines the most perceptibly.

In her last pictures, The White Sister and The Son-Daughter, two lulus, if you ever saw one, Helen Hayes showed a sickening coyness which grew more aggravating with every scene. Miriam Hopkins has had fortunate variety in her work; she had a difficult part in The Story of Temple Drake, which needed all the skill she brought to it to keep the picture completely out of the gutter. Joan Crawford has become a Great Lady—and a poorer actress; and, day by day, Miss Shearer works farther from her goal—a composite of Gertrude Lawrence and Duse. The middle-aged men. Frank Morgan, Adolph Menjou, Beery, the Barrymores, are too old at the game to be influenced. (There are no young actors in the business worth spoiling.) The girls have to do most of the dirty work, and few of them will be able to survive two years of it without paying for their huge salaries with a greatly reduced ability and usefulness.

The unique personalities, like Dietrich, who never have to act, but merely pose while their directors and modistes work on them, are fortunate indeed; fortunate, too. are the dozens who couldn't be hurt if you dropped them off the Empire State Building.

■ A SAD EXAMPLE.—You can see the difference between all this and really acting, if you watch the leading characters in Goodbye Again. This neat little play of last season has to have acting; the spirit of fresh comedy has to come from the leading man, in particular, but Warren William has been in too many stenographer romances to walk without a director's crutch. He smiles blandly to himself, and talks baby talk, in order to let you know just how funny he thinks his business. Miss Blondell has a faint idea of what she is up against, but in her big scenes, she falls quickly into the diction and general manner of the gun moll she has faithfully played for Warners these last three years. From a civilized comedy, these two turn it into A Night In A Turkish Bath.

Continued on page 56

(Continued from page 46)

For some odd reason, which a Hollywood psychiatrist might explain.the best part in the show—the tolerant, graceful Mid-Western business man—was turned over to a low comedian whose lines were killed, and who throughout the picture seems momentarily about to fall down a flight of trick stairs.

You may remember that we used to blame all these run-of-the-mill mistakes on the ultimate inadequacy of the scenario writers, yet for two years the best men in the writing business have worked from time to time in Hollywood, and one might conclude hastily that, like the actors, the enervating air of the picture industry finally had gotten them.

According to their records of several months ago. the large corporations had in their stables dozens of writers who couldn't, for any money, write Midnight Mary; among them were Clemence Dane, Robert Benchley, G. B. Stern. Wilbur Daniel Steele, Charles MacArlhur, Robert Sherwood, Lawrence Stallings, John Van Druten. John Bright, Francis Goodrich. Bonn Levy, Joseph Moncure March, Bayard Veiller.

You might wonder how any one of these competent workers could, half-soused, and with one hand behind his hack, turn out some of the movies we have been considering. You'll find the answer in Once In A Lifetime. While such men remain hidden. the following typical Hollywood workmen are now writing scenarios for almost the whole production list for this month: Stuart Anthony, Edgar Allen Wolff, Earl Baldwin, Joseph O'Kesseling, Humphrey Pearson, Robert Presnell. Thomas Buckley, F. McGrew Willis, Frederick Brennan. Jane Storm, Jane Murfin.

MILD AMERICANA.—This Is America is a well-edited collection of newsreels, accompanied by a speech which is pleasant and neither offensive to the car nor the intelligence. Produced by Joseph Ullman, Jr., 'and edited by Gilbert Seldes. the subway sage, the picture consists of a series of news clips from the war's end till now.

Some of these you may have seen before, but in general Mr. Seldes includes only scenes which have a cumulative importance. Thus the clips of the strikes of 1920-22 (easily the best in the picture) carry us into scenes showing the automobile boom, culminating in the Coolidge market and the Hoover bankruptcy.

He shows us those very important hits of Americana that should he preserved: channel swimmers, pie-eating champions, Tom Thumb golf. There is one splendid clip of a Billy Sunday speech: there are some fine scenes of the Sacco-Vanzetti agitation.

One can, of course, sympathize with the job that faced the producers: they had to make selections from literally millions of feet of film. However, just for the record, they should have given us the faces, and the speeches, of Mr. Roy Haynes, Harding, Mellon, et at, from the beginning to the end of prohibition, instead of having Mabel Willebrandt and a few latter-day saints to indicate the really dominant social problem of this era.

Then, too, the period of 1931-33 was carelessly handled: the scenes of unemployment were almost entirely of Sixth Avenue or of the squatters on the hanks of the Hudson. There must he thousands of exciting pictures taken in manufacturing towns that would have been more to the point.

Dr. Reisenfeld entirely botched the job of supplying music for the picture. Had he done the obvious, and only possible score, we should have had popular theme songs from the days of Over There right up to Stormy Weather, and This Is America would have been more valuable.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now