Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Gay Social Whirl Encored

Itemizing Some Further Way Stations in the Merry Round of Society's Gilded Cage

CHARLES G. SHAW

IN a recent paper, published in these pages, I made so hold as to touch upon certain pastimes currently enjoyed by Society. The Bohemian evening, an Opera Monday night, the formal tea, and other standard models of polite rejoicing, were reduced to their simplest terms. But the list was left incomplete by half. The present thesis, therefore, undertakes to summarize the vital features of those fetes and frolics unrecorded in the former tract.

Let us first of all consider the dinner with bridge. Invitations for this event may he by letter, card or telephone and will he received anywhere from weeks ahead to a few hours. 8:3o P. M. is the usual designated time, which means somewhere in the region of, say, quarter past nine. A dozen in all (six men; six women), let us imagine, are present. The customary rounds of cocktails have been passed, swallowed, and contents noted, followed, in turn, by the exchange of the traditional witticisms. With a sudden gust of animation the company then troops in to dinner, arranges itself according to the gilt-edged cards before each plate, and proceeds without any further delay to a consideration of the more succulent scandal-items circulating at the moment.

From grapefruit, through the guinea hen, down to the frozen biscuit glacé, the pageant of overhauled reputations passes in review, without an intermission. The reasons for the Jerry Carfax separation are thoroughly gone into, as is also the Endicott divorce, not to forget Maude Demarest's latest "affair", and even the sudden Pringle-Sims marriage. After a brief interval (during which the ladies withdraw, leaving the men to lie shamelessly over the coffee about their negotiations in the stock market), a general re-assembly takes place, partners are paired off, and the fascinating business of Contract (orchestrated with groans, looks that could kill, sighs, biting of lips, argument, and the gnashing of teeth) is begun.

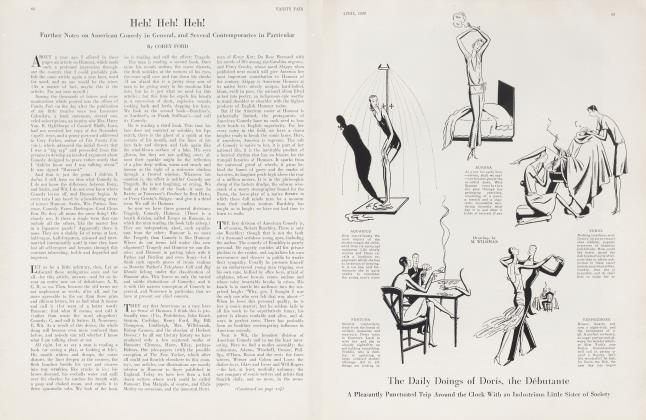

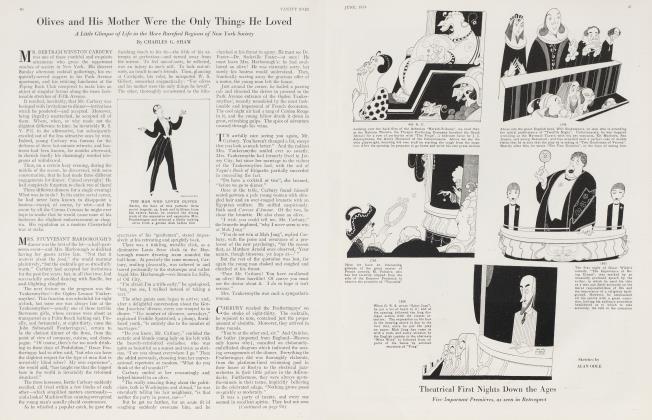

FOR our next venture into the world of fashion there is that piteous fandango known as the "coming out" party, of which numberless specimens are exhibited each season. Built around the débutante as a nucleus, the more formidable brand will in due course involve several hundred guests, a trio of hands, and two columns in the society pages. Let 11s consider one of this kind. A Park Avenue hostelry has been engaged for the night and, ranged in company-front formation at the entrance to the ballroom, stand the parents with their terrified little daughter, Clarisse, who, at the stentorian announcing of Crimes (the hired second man) forces a smile and nods sheepishly to each of the arriving guests, few of whom she is even acquainted with. Amid a clump of cacti and rubber plants one of the orchestras hangs away. A stagline of youths embellishes the centre of the dance floor; some tail-coated, hut most in dinner-jackets. A few more sit out with pink and-white young women on the stairs. In an alcove, another group pummels its way to reach the howl of sauterne punch. Here and there several with wilted collars and dripping brows take swigs from friends' flasks, while already a number plot to slip away and join up at the Cotton Club. "Don't forget—a week from Tuesday," "I want you to know my sister,"⅜ "Can't Sunday, dear. We're sailing on the Îie, Saturday," "Will you please look at that Gifford girl!" and other staccato quips may he heard, while the more mature faction (friends and relations of the family) pass the time in fat-jowled conversation or seek distraction at the card table. A little after midnight the second band strikes up the supper march and there is a universal scramble for partners, through the din of which a Lithuanian string quartette renders torch ballads. After a repast (consisting of a cup of bouillon, a spoonful of scrambled eggs, two lumps of ice cream and a saltine), seasoned with promises to dine with the So-and-So's on Wednesday, the third hand takes up the burden, bravely carrying on till the strains of Home, Sweet Home and Good Night, Ladies fall upon the sma' wee hour.

ASSUREDLY the theatre is rich with curious incident, with odd and strange event, with weird, fantastic memoir. Among which, the fashionable "opening" cannot well he omitted. Everyone—that is to say, "everyone" —is, of course, terribly late. There has been the usual confusion about the tickets (sent to the Union Club by mistake) and what with the traffic congestion it is exactly 9:27 before Lillie Grafton's party finally straggles in like a herd of immaculate lost sheep. The seats being five off the aisle, there is naturally a certain delay in getting located and then, of course, the usher has to be sent hack for programmes, so it is finally intermission by the time everything is actually settled. At this stage all proceed to rise and push their way back into the lobby, where other friends (equally late) are joined over chit-chat and cigarettes. On the return to the seats the curtain has already been up several minutes and a repetition of their initial entrance is undergone. Fay Ancaster, in the meantime, has, somehow or other, lost her programme, which misfortune she broadcasts in a high mezzo-soprano, while Cliffee Jay and Blanche Vanderveer wave to and carry on conversations with suddenly-discovered chums sprinkled anywhere within a radius of ten rows. Sheila Prime, in a new Patou creation, with the Perry Huffs, is spotted in the left stage-box, much to the delight of Jack Grafton and, with an almost deafening shriek, Kay Bliss points out Elsie de Wolfe and Mayor Jimmy Walker sitting just in front of Texas Guinan. "Isn't it too amusing!" bubbles Lillie, the while attempting to make out whether or not the blond young man in the second row centre is Colonel Lindbergh. Across the aisle, Moe Katz (brother-in-law of the producer) is mistaken by Teddie Lake for Somerset Maugham, while a portentous cloak and suit buyer in G-7 is pointed out by Laura Fellows as Mr. St. John Ervine. "Too, too thrilling for words," gushes Blanche, shoving her elbow in the eye of the ex-bootlegger on her left. "We simply must come again tomorrow night."

There, too, is the haut ton wedding reception, following the church ceremony, and held, let's say, in the apartment of the bride's family. The line of motors outside reaches a good three blocks, while the mob of reporters chauffeurs, nursemaids, photographers, tramps, small boys, and policemen at the door soon swells to bewildering proportions. An entrance achieved, however, and the hat and coat exchanged for a small pink check, an opportunity (slight though it be) to glimpse the surroundings is finally offered. At the far end of the living room (hung with fading Easter lilies) the groom, bride and bridesmaids (in picture hats and yards of tulle) are drawn up in line, receiving the congratulations of the day.

"NEARBY is posted the father of the bride i' (well-edged) and a few feet further on, the mother, half laughing, half weeping, and gesticulating profusely in all directions. Swarms of large elderly ladies, too, on tiny gilt chairs, gazing through lorgnettes, drape the offing, and in a corner stands a stranger who knows absolutely no one. A single bottle of champagne is produced for the needs of twelve adult men with thirsts of salamanders, while a lemonade-cup blooms untouched on an adjacent sideboard. Upon a curly-maple centre-table towers a mountain of wedding cake, done up in little white boxes with silk ribbon, and on a Chippendale affair, the presents, comprising (among other items) seventeen enamel clocks, nine soup tureens, twenty-three sets of dessert spoons, eleven pairs of silver candle sticks, and fourteen embossed picture frames, are displayed to the view of all. A chicken and lettuce salad is the main comestible (served by Parks, the faithful family servant, smelling strongly of '89 Sherry) together with a consommé that is neither hot nor cold and, later, little cubes of pistachio ice cream. After a while a hidden orchestra strikes up I Can't Give You Anything But Love, the bride's Sixth Form brother upsets the goldfish bowl with a crash, the three college classmates of the groom (who have been celebrating the great event since 5:3o P. M. the previous day) collapse in a body, there is a rush to the foot of the stairs, handfuls of rice splash the scene, and old Mrs. Fitzlister (who has come under a storm of protests) is soaked right in the ear with the wedding bouquet.

Finally I would note the formal private luncheon - given for visiting nobility. This is always, rest assured, the work of some well-meaning lady who has about as much in common with the guest of the occasion as an elephant has with a moth. The event is, nevertheless, promulgated far and wide, invitations are sent to a chosen few, and the distinguished visitor received with all the pomp and elegance the Messrs. Thorley and Sherry can provide. Trays of silver-sheathed cocktails are passed around along with little heart-shaped caviar-and-egg pates and it is almost half past two by the time the august company is ultimately seated at table.

(Continued on page 112)

(Continued from page 88)

Most of the male element, being stock-brokers, keep in touch throughout the function (by means of telephone messages, conveyed in whispers by powdered flunkeys) with the last-minute news of The Street, while the majority of the ladies, having discussed in cultured tones the previous night's dance at the Ritz, are forced upon the arrival of the avocado and quince salad to withdraw, in order to keep important bridge engagements. A few others (matinee bound) remain till the advent of the coffee, at which point the greater fraction of those left exit in a flurry of silver fox, chinchilla, and mink. The noble guest is accordingly told three coon-dialect anecdotes (hot off the floor of the Exchange) by one of the stock-brokers, and is eventually stalked to a corner of the conservatory where, under fire, he is dragooned into accepting four Long Island week-ends, three Florida fishing trips, and seven Tuxedo house parties during his brief five and a half weeks' sojourn.

With this dreadful scene we must momentarily close this chapter of the gay doings of those people known collectively as Society. Surely proof enough has been adduced to show that hearts aching with boredom may throb beneath the starched bosom and the Patou frock: and the supreme enigma is that our great and fashionable noblesse submit to these grim rituals, not for a night, but for years and years, until . . . But ah, we have omitted the fashionable funeral.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now