Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWhere Every Prospect Pleases

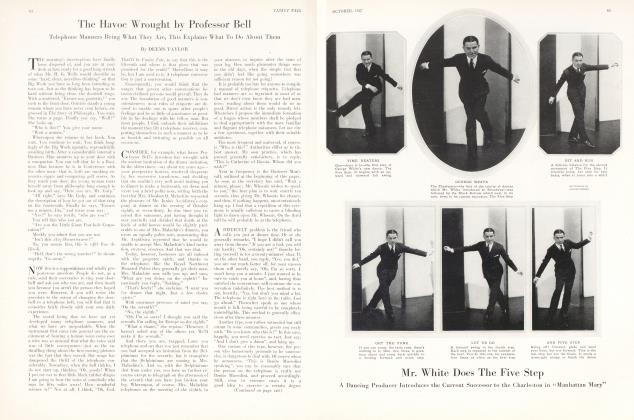

A Member of the Buying Public Comes Into Violent Contact With High-Pressure Salesmanship

DEEMS TAYLOR

IRAN into him—literally—when I came down to breakfast; he in a straw hat and Palm Beach suit, with a Kiwanis button in his lapel, I in an early American bathrobe that had long since acquired the violet's most notorious characteristics as well as its colour. I was not at my best, and I knew it. He ignored my costume, however, and proceeded to put me at my ease.

"Mr. Taylor? My name is Hubbel. I thought I'd drop in and see if I couldn't help you with your pump problem."

I must admit I was flattered. During the years that I have been tracking down fiction through the back pages of the Saturday Evening Post I have grown to realize that the really big and reliable advertiser never does anything so vulgar as sell anything; he solves problems. And likewise, it is only the very highest type of substantial, successful consumer—the kind who wears nose glasses and a clipped white mustache, and sits at a flattopped desk gazing out at the factory—who has problems to solve. Up to now, I had been forced to wrestle with my necktie problem unassisted by the Square Deal Gents Furnishing House, and Mr. Annino, on the corner, had never once even offered to help solve my spinach problem.

But Mr. Hubbel's opening words of greeting made me realize that M. and I had been justified in purchasing the Connecticut farmhouse that, six years ago, we had picked for our ancestral home (it is still referred to, locally, as "'the Dombrosky place"). For, obviously, we had risen out of the ruck of "consumer demand" into the Problem class, and were somebodies at last. Instinctively straightening the place where a white waistcoat should have been, I motioned Mr. Hubbel to take a chair. He had already done so.

NICE little place you've got here," he remarked kindly—"or at least I can see it's going to be, when you get it finished." I flushed with pleasure and wished M. were there .to hear. "I'm with the Aquapumpo people—as a matter of fact, I'm their general sales manager. We heard you were in the market for our product, and I made up my mind to come out here in person to see what I could do for you—"

Here was thrill number two. I had met salesmen before, of course: the bales of magazines that arrive every month are mute testimony to the number of middle-aged striplings for whose college careers I have voted. Moreover, I possess one of the handsomest and most complete collections of Fuller brushes in America, and know that a request from a stranger for an interview regarding "an urgent personal matter of the utmost importance" means that the Loved Ones are about to go without meat in order to pay another insurance premium.

But never before had I been face to face with a sales-manager, one of that race whose penetrating glance fixes you from the pages of the American Magazine, that sits at cleared desks reading graphs and sticking pins in maps, that gives talks on the "Old Selling Game" at business luncheons. At last I, too, was to have my chance to play that game, to match wits and get down to brass tacks and talk turkey with a square shooter and have my problem solved.

As a matter of fact, I had hardly realized the gravity of my problem until Mr. Hubbel began to talk. The years having rolled by, and an artesian well having been drilled (with platinum drills, I should judge), something with which to extract its waters seemed to be indicated. The only problem, as I had envisaged it in my simplicity, was to get a pump that would look after itself and cost practically nothing.

This, I may say, was not Mr. Hubbel's idea at all. He was there to help me, and in the process of being helpful he made it clear that I was confronted by a very complicated and serious situation. Had I considered, for instance, the question of Servicing? I had not.

"NOW right here, Mr. Taylor, is one of the biggest problems of all, and one which we are prepared to help you solve. You know, of course, that the Aquapumpo is made right here in the neighbourhood?"

"Of course," I lied heartily.

"Well, you see what an advantage you will have over other pump buyers. Something goes wrong, say in the middle of the night. You merely telephone our service station, where we maintain a crew of fourteen experts twenty-four hours of the day, and within twenty minutes a picked man is at your door."

This sounded a bit frightening. "But I didn't know your pump ever got out of order," I protested.

He gave a light laugh. "Well, as a matter of fact, those boys at the station get so few calls that they spend most of their time playing pinochle. Out of seventy-four calls we received last year," he continued, drawing a small notebook from his pocket, "seventy-one were the customer's fault." I looked conscious. "Why, usually three of them go out on one call, just to keep each other company."

"How does it work?"

He whipped out a folder and placed it in my hands. "This tells the story."

I read it carefully. It began: "Have you ever realized what it means to the housewife to have a steady, WORRYLESS stream of sparkling, clear water constantly at her command? No more back-breaking lifting of buckets, no more trips to the well in bad weather. Aquapumpo sees to that, silently, cheerfully, and at a cost of a few pennies a week. The hours you used to spend working a pump handle can now be devoted to the movies, or bridge parties, or to reading that latest book that all your friends say is so fascinating."

I handed it back. "Somehow I don't grasp the principle of the thing."

He raised a commanding hand. "You have gone straight to the heart of the matter. The vital feature of the Aquapumpo, the big message we have to bring to the American pump-consumer, is the impermeable gasket. You follow me, do you not?"

I nodded intelligently.

"The Aquapumpo works by centrifugal regurgitation, a method possible only with the Aquapumpo impermeable gasket. Mr. Taylor, I wish I could make you realize the years of patient research that our engineers devoted to working out that impermeable gasket, the millions of dollars that the Aquapumpo spent in order that it might keep faith with its public. . . . That, in short, is the essential structure of the Aquapumpo, and as you see, it is simplicity itself."

"ONE other thing, Mr. Taylor, I want you to consider," he continued earnestly, "and that is Pride of Ownership. Pride of Ownership," he repeated. Now, the Aquapumpo being made right here on the spot, you might meet one of the officials of the company at any time. Suppose you met Mr. Macnamara, our president—the Big Boss, the boys call him—on the golf links, or at the country club; and you should say to him, 'Mac, that was a mighty poor pump your people sold me.' How would he feel? So you can see that Pride of Ownership alone would compel us to turn out a product—"

"How much is it?"

"There's one thing, Mr. Taylor, that I want you to promise me," he said earnestly, "and that is, that no matter whether or not you get an Aquapumpo, you won't get a cheap pump. If you get one of ours, I'll be a hundred per cent satisfied; but even if you don't, I'll be fifty per cent satisfied, if you get a good one. I want above all to see this problem of yours solved right. And I don't want to see you spend a lifetime of dissatisfaction just for the sake of saving a few dollars at the outset."

I was silent, too moved to speak.

"By the way," he remarked casually, "it just happens that we have a sales drive on this week, and your order is just what I need to put me over the top. Besides, if you sign up today, I am in a position to guarantee you immediate delivery."

But I had tasted blood. This was salesmanship, and I liked it, and I lusted to hear more. So I put him off for two days, and sent for Mr. Nibble, of the Jerkwater Pump Guild. I didn't exactly send for him. I happened to open the front door after breakfast, and he was there.

Mr. Nibble was not like Mr. Hubbel. He was a small, silent man, whose lack of heartiness was atoned for by the persistence with which he was always on hand. I had five interviews with Mr. Nibble, and though I saw him depart twice, I never saw him arrive. The bell would ring, once, and one opened the door, and there was Mr. Nibble.

He, too, had been thinking-about my problem. The Jerkwater pump, it appeared, was made, not in the neighborhood, but in Kling, Colorado, which, as Mr. Nibble pointed out, was a great advantage, since the low rents in Kling enabled the Jerkwater Guild to maintain service stations throughout the country, each manned by a crew of fourteen experts. As for Pride of Ownership, the Jerkwater people had it to the highest degree. The Jerkwater pump itself was their one best bet, or, as Mr. Nibble phrased it, their Ambassador of Good Will.

Continued on page 130

(Continued from page 63)

I asked him how it worked, and he silently handed me a folder. It bore a coloured picture on the cover, showing a little golden-haired girl of five operating an artesian well pump while her father and mother, in the middle distance, played billiards. It began: "Can you realize what it means to your wife to have a steady, WORRYFREE supply of clear, sparkling water instantly at her beck and call? No more back-breaking—"

I silently handed it back. "How much is it?"

He looked grave. "Mr. Taylor, as one who has your best interests at heart, I want you to promise me that, whatever pump you buy, you "won't make the mistake of assuming that the most expensive is necessarily the best. I don't want you to spend a lifetime of regret just for the sake of saying that you have the most expensive pump on the market. By the way," he continued in a more conversational tone, "it just happens that we're having a sales drive this week, and your order is all I need to put me over the top. Besides, if you sign up today, I am in a position to guarantee you immediate delivery."

"I'll let you know tomorrow," I said.

The afternoon brought Mr. Gobble of the Little Giant Pump Co., Peru, Indiana. He was a shabby young man in a battered straw hat and was obviously badly frightened. "I heard you might want to buy a pump," he said.

"How about servicing," I demanded.

"I—I don't know."

"Have you any pride of ownership?" I pursued, relentlessly. He seemed staggered. "Well," I continued sternly, "how does it work?"

He timidly held out a folder full of graphs and diagrams. "To tell you the truth," he faltered, "this is my first week at selling pumps, and I don't know much about them. I've been in the piano business. You better let me bring over one of the engineers to explain it to you."

"How much is it?"

"Four hundred and twenty-two dollars and sixty-seven cents cash, plus six per cent on time."

"Are you in a position to guarantee me immediate delivery?"

"Sure. Business is terrible."

"I'll let you know tomorrow."

All evening I pondered, and finally dispatched three night letters. They ran as follows:

Hubbel Aquapumpo Inc

SORRY HAVE DECIDED TO PURCHASE CHEAP AND INFERIOR SUBSTITUTE REGARDS TO MAC

T ay lor

Nibble Jerkwater Pump Guild

HAVE DECIDED TO THROW MY MONEY AWAY BESIDES DONT LIKE CHILDREN MONKEYING WITH MY PUMP REGARDS

Taylor

Gobble Little Giant Pump Co

WRAP IT UP

Taylor

It wasn't a pump, but otherwise this is a true story. I don't know the moral.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now