Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Nowbecause he loved her

HENRI DUVERNOIS

a wife is consoled to find in her slightly dull marriage its one small, saving disgrace

After six months of sublime happiness, Cyprien Boizillon said, one day, to his bride;

"Darling, now that our perfect honeymoon is over, I shall simply have to go back to work." His expression was grave and exalted, and his voice 'held a new, solemn note; Julie looked at him in surprise.

"But, of course, my love," she exclaimed. "I didn't mean to be greedy about keeping you all to myself . . . and I am sure that we shall get on very well, your mathematics and I!"

"Well, I dread it a little, I must confess. We'll have no more lovely, long mornings together, for when I'm working I must get up at seven and stay in my study until noon, then again from two o'clock until eight—and from ten until midnight on the evenings when we don't go out!"

Madame Boizillon acquiesced gently in this new and rather rigorous order of things. She told her husband that she asked only to have a little corner of her own in his study, where she would install her chaise-longue and be quite contented reading, and smoking Russian cigarettes. Perhaps he would come and kiss her from time to time—wouldn't he? And, of course, she wouldn't be there too much of the time . . . occasionally she would go out to tea, at a friend's house or at her mother's. Perhaps she would take up the piano again, or her water-colours. . . . Anyway, it would all be very pleasant, and he needn't worry about her; she would be quite happy.

But when she was alone, she reflected a little plaintively (for she was a romantic woman, and liked to think in metaphors) that their life together had been so far, like a path through a delightful garden where each successive row of flowers stood for some delicate

memory of romance. They had become betrothed in the perfume of lilacs and roses— married in an intense fragrance of orangeblossoms—and their wedding trip was a memory delicately scented with eucalyptus and mimosa. Now she had reached a turn in the path, and a mist had fallen over the rest of the garden. What lay beyond, she did not know; but she suspected that its perfume might be a little less heady.

Cyprien set himself doggedly to work; and Julie, stretched on the chaise longue and absently fingering the pages of a novel, contemplated her husband through a frenzied cloud of mathematics. It was not a pretty sight. Clad in a dressing gown distinguished for its warmth rather than for its elegance and a pair of old grey trousers, his feet shuffling in shabby grey slippers, his collar open, hair on end, brow furrowed and lips pursed in thought, he looked like a rather dirty but studious schoolboy painfully absorbed in his lessons.

"You are amusing, my treasure," she murmured once, watching him. He did not answer; he had paused in his writing, apparently lost in a problem, his eyes glassy and transfixed. Then, inspired anew, he resumed his feverish scribbling. Julie smiled tenderly, and said in a voice warm with congratulation;

"Now you've got it! My poor dear . . . you toil away as hard as though I'd brought you no dot at all."

When this sympathetic overture met with no response, she went on; "You've been working now for half an hour, and you look quite as though you might have a rush of blood to the head. I don't want you to get sick, you know! Aren't you hungry? . . . Thirsty?

Would you like me to order oysters for dinner, darling? Oh, by the way, what do you think I found out to-day? Florence, the cook, has been putting rouge on her lips! So she can taste the soup better, I suppose.... I really don't know what the world is coming to. Am I disturbing you? I'm not, am I? Do you love me, darling? Kiss me. . . ."

He got up and gave her an absent-minded kiss, flavoured with a vague, scholarly odour of ink and old books. Lilac, orange-blossoms, mimosa and ink, she reflected ... a conjugal tragedy in four odours. Well . . . sighing, she lay back on the couch again, yawned and threw her book violently to the floor. It made Cyprien jump, but she ignored him, brooding with a hostile eye, an eye already glittering slightly with rancour, upon this mighty work of his in which she could have no part.

After that, she refrained elaborately from adorning her husband's study by her presence. It was not thus that she had expected to play the role of Muse; rather, she had imagined a charming tableau composed of scraps of romantic impressions stored in her mind. It would be like a scene from La nuit d'octobre, which she had seen at a charity performance . . . the man dressed in pensive black, fingers thrust dramatically through his dark, flowing locks; the woman lovely in white, a protective, encouraging hand resting lightly upon his shoulder. The reality was too bitterly different from this delightful picture.

Disillusioned, she sought diversion by going out every afternoon, to tea, to a matinee, to the couturier's. She even took fencing lessons in a gymnasium and lessons in dancing from Madame Malorque, a mad, ancient creature addicted to high kicking, spiritualism and rum in her tea. She came home late—silent and in a bad humour more often than not.

And Cyprien began to wonder a little.

One morning the maid brought him an envelope alarmingly striped in red, yellow and green, and addressed to him in a sprawling hand. He tore it open, and read;

"Monsieur; I shall not sign my name, but you will know me some day. While you spend your time scribbling, your wife is not twiddling her thumbs. You are blind to a great deal, and I, as an honest person, pity you . . . unfortunate fool that you are."

Cyprien at once suspected that this letter was from the cook whom Julie had dismissed for rouging her lips. But he was a little uneasy, nevertheless, and resolved to question his wife.

When she came in, at six o'clock, he asked her casually; "What did you do to-day? Where have you been?"

She laughed, and put her arms around him. So he wanted information, did he! But why? Such trifles wouldn't interest a man like himself, a great mathematician. Oh, well. .. there had been a spiritualistic seance at Madame Malorque's—in the dark. But it had not been a great success, because all the ladies who were present had laughed too much. They were women of a certain kind, of course, the kind that came there only to carry on flirtations with the gentlemen spiritualists. After the seance ....

But then Julie fell silent. "Never mind about afterward," she concluded abruptly. And she went and stood in the window, tapping irritably upon the pane.

"Are you bored here, with me?" asked her husband humbly.

She shrugged. "Well—it's not wildly exciting, you must admit!"

Her back was still toward him, but her shoulders drooped, her voice broke pathetically, and he thought that he heard a stifled sob. His distress drove him to a sort of angry pleading. What would their life be, he demanded, if she went on lavishing all her gaiety, all her animation upon people outside of her home? He worked hard, and when his work was done, he liked to have a smiling face about him. He went on talking about himself. . . . She remained silent, indifferent.

From that time he attributed every word that she spoke, every move that she made to this discontent that so grievously racked her; he became the victim of a miserable, exacting jealousy, a spying sort of jealousy, dark and shameful. If she seemed quiet he suspected her of sadness; if she brightened a little, he saw hysteria in her animation.

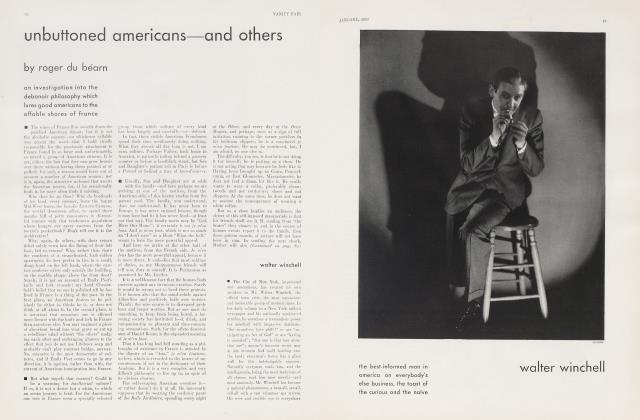

At length, to put an end to these doubts that tortured him, he applied to a detective agency. There he talked with one of the staff of detectives—a man who, the manager assured him, was experienced, tactful and discreet. Cyprien thought him rather furtivelooking, for he retained, even in his office, the professional manner of moving about the room by feeling along its walls ... he could not even open a door without first creeping up on it. He had a melancholy mustache, and an unhealthy pallor; but he allowed himself a single, wistful note of gaiety in a pair of yellow gloves and a cane topped by a gilded monkey's head. His name was M. Alfred.

He listened attentively to Boizillon's story, responding occasionally in a doleful voice, with phrases whose pretensions to grandeur were slightly marred by a startling ignorance of grammar. When he had heard the case, he declared gravely that he was willing to undertake it.

"The best thing about him," the manager pointed out enthusiastically, "is that he has an air about him; he can mingle anywhere. Just as much at home, he is, in the faubourg St. Germain as at Belleville. We often use him for clients of the nobility . . . why, even that cane of his was given to him by a countess —wasn't it, Monsieur Alfred?"

Continued on page 74

Continued from page 51

M. Alfred looked fondly at the cane. "I get results, and that's the truth," he admitted, "and then the people I've been of service to send me a little something—as it's only right they should, of course—and sometimes a little souvenir of themselves. . . ."

Julie's melancholy, during all this time, had deepened to a mood of black despair. Life seemed a burden to her, empty and mocking; she was no longer even sure of her beauty, since nobody appeared to notice it. She had, she told herself pathetically, no admirers.

"You are very happily married," men told her, with polite regret. And then they let her severely alone. It was maddening.

Even at Madame Malorque's, where ancient horrors sixty years old succeeded in having rakish flirtations, she had not met one man, young or old, who could or would give her one little word of tribute, of admiration to flatter her vanity! Had she become ugly or stupid? She had tried to attract M. Lepierval, a dissipated Romeo who frequented that salon; but in vain. In vain she had attempted to enchant M. de Mirmont, whose emotional capacity was usually such that he was unable to ask a waitress for a glass of water without putting into the request all the tremulous passion of a declaration of love. Frépal and Verteuil, who specialized in paying court to unhappy wives, treated her with an offensive respect. Alas! she yearned to play with fire, and there was none . . . only ashes everywhere; and she had arrived psychologically at a crisis where the approval of her mirror did not count, nor did the vague admiration of a husband who was no longer a bridegroom. . . .

But suddenly . . . she was transformed, as if by a miracle! Her fretfulness gave way to amiability, her indifference to animation. She spent every afternoon away from home, and she came back radiant with good spirits. She put little nosegays of spring flowers on her husband's desk, and from time to time embraced him in a motherly fashion, as though she would console him for something.

"Get busy, by heaven!" Cyprien besought his agent. "There must be some gaps in your reports . . . redouble your vigilance!"

"We'll get there, we'll get there! Don't get excited ... if there are any results to get, M. Alfred will get them!"

Julie came home one evening with eyes so brilliant with joy that poor Cyprien, wounded to the quick, welcomed her with no little irritation.

"I forgive you your bad manners," she told him generously. "You work too hard, darling, and it makes you nervous. But I would like to know what would please you; when I'm sad, you complain—when I am gay, you complain even more. . . ."

"That's just it . . . you're too gay And I can't help wondering exactly why you are so gay, so suddenly."

There was a little silence; then Julie said hesitantly; "I'd like to tell you . . . but will you believe me?"

"Go on."

"Well, it's just this; You know, darling, that I'm a little bit of a flirt —oh, it's no crime! I love you with all my heart, and it is because I love you that I want to be admired by other men—to have them find me desirable, so that you will be prouder of me, Cyprien. All women are like that, and it's silly to say they aren't. Well, the w'ay things were until just recently, I might as well have worn a placard with 'I love my husband' written on it. Men paid no more attention to me than as though I had been an idiot or a freak . . . perhaps it was because they admired you so much that they dared not. . . . Shall I go on?"

"Co on."

"Well, about a fortnight ago, the spell was broken! I have a suitor, darling, a beau at last! If you only knew how amusing it is ... of course, he's not a very dazzling Romeo. You'd be sorry for him if you saw him— he's a rather pathetic creature. But he follow's me everywhere I go . . . when I'm shopping, he waits outside the door until I come out, like a faithful dog. Of course, he never dares speak a word to me, he only worships from afar as though I were his idol—imagine! He probably w'rites poetry to me when he can't see me . . . you're not angry?

"If you could see him! He has the saddest mustache, and he wears yellow gloves and carries a cane with a monkey's head on it. And he follows me through rain and snow until sometimes he has mud up to his ankles— but his devotion never falters. When I'm having tea, I say to myself; 'He will be outside the door, dreaming of me, waiting for me'; and when I go out, there he is!" Julie paused, reminiscently. ... "I lead him a pretty brisk chase sometimes; and if he thinks lie's going to lose sight of me, he has the most desperate look and simply pushes people over to catch up with me again. . . .

"Darling, I can't help it if it flatters me. I'm not above a little weakness, you know . . . but there's no harm in w'hat I'm doing. I just w'anted a little romance to feed my vanity, to give me back my own self-confidence; now I have it, and I'm happy. Are you angry with me, Cyprien?"

She waited wistfully for her husband to speak; and Cyprien took her in his arms.

"Angry with you, my angel?" he cried. "I adore you!"

The next day, Boizillon paid a brief visit to the detective agency, and asked to see M. Alfred. He gave him a louis, and said;

"I am entirely satisfied with your services; in fact, I should like to make arrangements at once to engage you exclusively for the next six months!"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now