Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe devil a monk would be

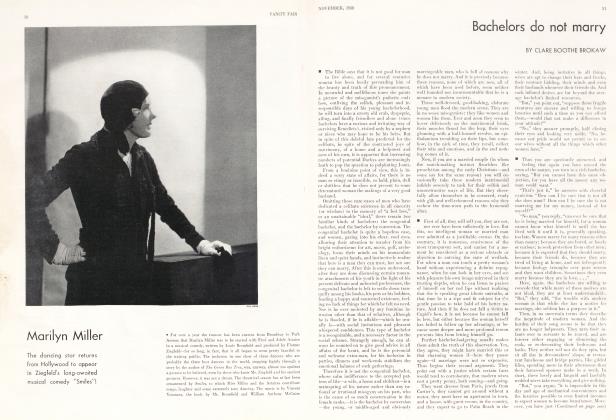

HAROLD NICOLSON

The dark potentialities of Mother Goose and Mickey Mouse, revealed in the stern light of modern censorship

I have just read, in the newspaper, that the Board of Film Censors in Germany has issued an interdict against Mickey Mouse. The latter had been guilty of conduct "liable to wound the patriotic sentiment of Germans and to bring our army into disrepute".

I have not seen this particular Mickey Mouse story, but I understand, from the paper, that it represented an escapade in Flanders, in which Mickey figured in a French kepi whereas the cat army were booted and spurred and bore on their heads what was unmistakably the old Prussian Pickelhau.be. Mickey, it was obvious, had taken the side of the Allied and Associated Powers, and I have little doubt that the opponents of Mickey were represented in a wholly unfavourable light. They generally are. "This," I said to myself, "is characteristic of all that was worst in the old Imperial Germany. They have no sense of humour and no sense of proportion. By taking Mickey seriously they create the very danger which, by their censorship, they desired to avoid."

So indignant did I feel on Mickey's behalf that when, a few days later, I met a member of the German Embassy at a luncheon party I asked him how it came that his censorship authorities could have been so silly. He replied that the authorities had been absolutely in the right. Had the film been shown in public, it was certain that some ex-service men present would have created trouble. People who fought in the Great European War suffered much from that experience, and are apt to get annoyed when the thing is treated as a joke. The German soldier would resent seeing himself represented in the semblance of a fierce hut clumsy cat. There would have been a riot, and the authorities were fully justified in prohibiting the film in advance.

I found at the time no very ready response to this argument, and it was only later, while walking back from luncheon across the Park that I examined myself seriously on the censorship question and endeavoured to ascertain what I really felt about it. I found that my ideas, when exposed to the cold light of reason, were a mere jumble of personal prejudices or second-hand opinions.

In principle I am in favour of free speech. My blood seethes to my head in waves of anger at the thought that any outside authority should exercise a censorship over what I think or say. Willingly would I go to the stake rather than submit to any such indignity. And yet, when I consider the censorship in relation to the works of others, when I take concrete instances of unrestrained publicity, my indignation begins to waver and I am not so absolutely certain that I should banish the censorship completely from the face of this ignorant, emotional, and muddleheaded world.

What should I do, for instance, if I found my daughter at the age of sixteen studying the works of Sigmund Freud? Were I consistent to my principles of liberalism I should applaud the girl and provide her, as a corrective, with the works of Jung. But I know that in practice I should do nothing of the sort. I know that in practice I should smack the child sharply on her yellow head, saying to her, "Effie, never read that beastly book again".

Naturally I could justify such action upon logical principle. I could say that Effie at sixteen would not possess sufficient sexual experience to be in a position to check the tortuous and involved imagery of Freud by reference to her own average of knowledge. That to read Freud when one is immature is to read him undiluted by the water of self-realisation. And that spirits, when absorbed in their undiluted state and in large quantities, are bad for the human constitution.

All this I should say, and then I would compensate myself by a fine phrase of extreme liberalism. "It shocks me",—thus would I exclaim, "to find Effie reading Freud at the age of sixteen. But it would shock me still more were I to discover that Effie at the age of twenty-six had never heard of Freud." That sounds magnificently enlightened: it indicates a masterly control of one's own theories. But in practice it is as illogical as anything else.

For, the moment that I admit that I am justified in banging Effie on the head for reading Freud, I am admitting that in certain circumstances, and at certain stages of mental development, people should not be allowed to read what they want. By this admission I have flung the gates wide open to the enemy. I may quibble over it a bit, arguing that parental censorship is different from governmental censorship, and that even parental censorship should in any case be abolished after the child is twenty-one. Such reservations are merely little palisades of lath and plaster erected to cover the breach which I have myself opened in my defences.

There is no half-way house between admitting that all censorship is always wrong and admitting that some censorship is sometimes right. And when one reaches the latter admission one may as well give up the struggle immediately. For one has reduced the case against censorship to a mere matter of expediency. And expediency is a wholly relative term. It was doubtless "expedient" for the German Authorities to jump with heavy boots on Mickey Mouse. But on this plea any Government could defend the suppression of all views which, to them, are inconvenient.

Let me take a further concrete instance. There is a Russian film entitled Storm Over Asia. It is an excellent film and contains some of the finest motion photography that I have ever seen. As a work of art it deserves to be exhibited throughout the world. To censor it would be to censor what is unquestionably a work of outstanding merit, and we are all agreed that such would be an evil thing to do. And yet, and yet . . .

Allow me to explain the matter. Storm Over Asia is a Bolshevik film designed to represent the British Government and army at its worst. I have no objection to that. If the British Government and their representatives abroad really behaved as atrociously as depicted it is all to the good that they should be exposed. If the thing is palpably untrue, then it is better that its lying qualities should be exposed to the ocean of public criticism than that their poison should be distilled into some secret and confined canal. That would be the sensible and liberal argument to apply to this circumstance. And yet I am not really certain that it is the sensible argument.

The film, for instance, is supposed to represent the conduct of a British expeditionary force in China. It is deliberately intended to arouse hatred in minds where no hatred existed before. It achieves this aim by distorting the facts. But it does worse than this. It is calculated to inspire the ignorant Chinaman with the idea that he can with impunity approach close to a machine gun and that the soldiers who fire that gun will incontinently run away. The Chinese are a simple-minded race. And I pity the fate of those wretched coolies who might be tempted to behave in the triumphant manner in which these coolies behave on the screen. Now, were I the Admiral or the General responsible for order, let us say, at Shanghai, I should certainly prohibit the exhibition of Storm Over Asia. I should not prohibit its being shown in London or in New York. But I should by no means be so sure of myself were I Mayor of San Francisco. And yet in principle I remain fervently opposed to the suppression of works of art for political reasons.

Take again that excellent Russian film Potemkin. It represents a successful mutiny upon a Russian cruiser. It is supposed to be historically accurate, whereas in fact it denaturalizes every incident which actually occurred. Here again the main object is to arouse hatred. And here again the unarmed triumph easily over the armed—a highly dangerous doctrine. I should not permit the performance of Potemkin before any large number of sailors, or, rather, I should only permit it accompanied by a convincing explanation of what really happened, and a thorough exposure of its lies.

(Continued on page 94)

(Continued from page 52)

Now if in three concrete cases, in the case of Dr. Jung and Effie, in the case of Storm over Asia, in the case of Potemkin I am prepared to admit of a modified and regional censorship, then I might as well abandon my position completely and say that censorship must exist. Very well, I do make that admission; hut I qualify it with the reservation that it must he intelligently exercised. The onus of justifying censorship must rest upon the censor. If he blunders, he must be removed.

Delicate indeed, and tentative, must he the task of any censor. For how do we know what in effect influences the minds and character of the illiterate or the young? They have little sense of the hypothetical, nor are they often able to transfer into terms of their own experience facts and feelings which are presented to them as the experiences of others. There is an element of chance in early influences, and in the lives of the Great we are all too often misled by false inferences.

I should conceive it possible, however, in every country to create a jury of censorship, a body reserved for people over the age of thirty and under the age of forty-five. Such a jury would he empowered to recommend the suppression of any play, book, or picture which, by a two-thirds majority, they considered liable to provoke danger or to cause harm. They would he limited by their terms of reference. They would he empowered to recommend the suppression of a work on political or religious grounds solely because that work might he liable to cause a breach of the peace. No weight should he given to the consideration that the political or religious views expressed were at variance to their own.

In sex matters they would he allowed to recommend suppression only in cases in which a two-thirds majority of their members pronounced a work to be definitely pornographic in intent. The test they should apply would not he their own personal likes or dislikes hut the practical effect of any work upon the public mind. Such a jury would, and perhaps with reason, have prohibited that particular Mickey Mouse from being performed in Germany. But they would not have suppressed The Well of Loneliness and thereby given to that arid work an overwhelming popularity and advertisement which, if left to itself, it would never have acquired.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now