Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowLife among the snobs

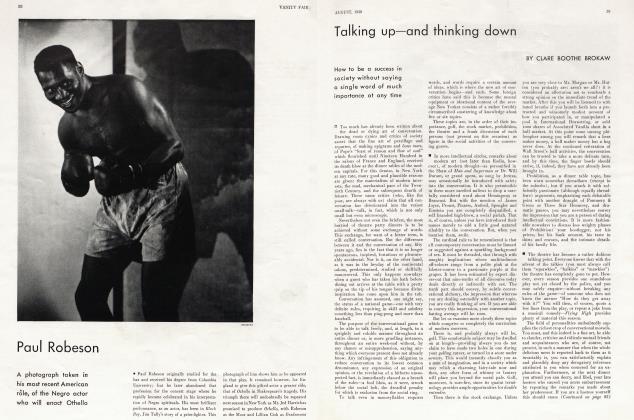

CLARE BOOTHE BROKAW

Intimate glimpses of the New York social battlefield and the celebrated rivalry of its two leaders

FUNDAMENTALS OF ARISTOCRACY: The scene was Newport, the first weekend in September. It was in fact a fine Sunday afternoon preceding Labor Day. Mr. Goadby, one of Mrs. Towerly's house guests, had just returned to Mrs. Towerly's ancestral country seat, The Billows, from a pleasant round of golf on the Newport Country Club links. As he crossed the imposing, ugly and much photographed threshold, passed through the palmlined marble corridor, and attained the cretonne and mid-Victorian mahogany sanctuary of his bed-room, Mr. Goadby was in high spirits. Since his arrival on the previous morning he had dined well, played agreeable bridge and creditable golf, had bathed on the sacred crescent of Bailey's Beach, in surroundings which were enviable, with people who were correct. In short, his stay had been a successful one: he was a guest of Mrs. Towerly.

Therefore Mr. Goadby's surprise was great when, entering his room, he saw that his town clothes had been neatly laid out on the bed and that his suitcase was almost packed.

He immediately rang for the valet.

"Dudgeon," lie said, "my bags are packed. You have made a mistake. I am staying over Labor Day."

"Mrs. Towerly instructed me to pack your things this evening, sir," said Dudgeon solemnly. "Here are your reservations on the Commonwealth to New York."

"Well," said Mr. Goadby. "Well."

"Is there anything else, sir?"

"No."

When Dudgeon had gone, Mr. Goadby flung himself in a chair and thought furiously. By some casual bon mot which had been misinterpreted, some unconscious lapse of taste, some unintentional insult to her high traditions and delicate sensibilities, had he offended this dowager Duchess of Newport, this uncrowned queen of American society? Undoubtedly, he had. For there were his bags, ominously packed. He knew his hostess too well to hope that an apology (for what?) would avail him anything. Mrs. Towerly was relentless, and from her social edicts there was no appeal. Gloomy thoughts of a forthcoming social exile filled Mr. Goadby with acute discomfort. There came a knock at the door. It was Mr. Hewitt, another guest. He entered, his forehead puckered and damp with beads of perspiration.

"I say, Goadby, my wife and I must have offended Mrs. Towerly. We are being packed off to town on tonight's boat. God, what shall we do?"

At this, Mr. Goadby's own frown relaxed. He waved a comprehending hand in the direction of his suitcase.

"I see it all now," he said. "Mrs. Towerly asked us for the week-end, but she has forgotten that Monday is also a holiday—Labor Day."

He rang once more for Dudgeon.

"Dudgeon," he said, "will you tactfully remind your mistress that tomorrow is Labor Day. It has undoubtedly slipped her mind."

"Madam is resting," said Dudgeon, "but I will tell her."

He went and the two guests, relieved of the thought of a social Siberia, and the unbearable prospect of a holiday in town, which (according to the society columns) was absolutely deserted, began to discuss their golf scores of the morning.

Dudgeon returned.

"Mrs. Towerly says she will bid you goodbye at dinner," said Dudgeon. "And Mrs. Towerly also wishes me to say," he continued, the echo of a reproach in his voice, "that the Towerlys never observe Labor Day."

ECHOES OF THE TUMBRILS: Mrs. Towerly was having a dinner party. In the high white and gold drawing room of her great Fifth Avenue mansion, her nineteen guests awaited the arrival of the twentieth, who was also the guest of honour—His Excellency, the Ambassador of D-. He was quite late and the other guests, discomfited by the glint of impatience in their hostess' pale, autocratic eye, stood in small, stagnant groups, chatting in strained undertones, which were occasionally punctuated by an artificial feminine laugh, or a nervous masculine cough.

"His Excellency! The Ambassador of D-," Dudgeon announced in a loud voice.

There was a general shifting, polite silken whispers and delicate sighs of relief.

Mrs. Towerly, instantly detaching herself from an obsequious group of satin gowns and boiled shirts, swooped down upon her guest of honour, an avalanche of black lace and enormous, badly matched pearls.

"My dear Ambassador," she intoned.

He bowed over her plump, cold hand.

"I am sorry to be so late. My motor car was held up by a parade. A parade of bolsheviks, if you please. Marching up Fifth Avenue. Garment workers on strike . . . red banners . . . Down with capitalism . . . Ridiculous."

Mrs. Towerly recoiled, horrified.

"And the police?" she asked.

"Oh, they did nothing—let them pass."

Mrs. Towerly's majestic frame assumed even more majestic proportions. Turning to the butler, she spoke in a voice of high command, of regal resolve. "Go, Dudgeon," she said. "Lock all the doors, bolt the windows and," she added, "put the gold service in the vault."

Her guests looked at her, their faces mirroring genuine surprise, the first natural expressions they had worn since their punctual arrivals.

Throwing back her head, Mrs. Towerly walked to the window, drew back the velvet portières and gazed, with resignation on Fifth Avenue.

"The Reds will come here first," she said with a quiet and infinitely noble air. And then she looked over her shoulder at His Excellency, a jewelled hand at her throat. A wan smile played on her thin lips. . . .

"They will come here first," she said, "for I am the Marie Antoinette of America. . .

A FAMILY LIKENESS: The Summer that the young Prince of Wales had visited America, Mrs. Towerly had been very ill indeed. On the shoulders of Mrs. Topping, her dearest friend and bitterest rival, had descended the honour of entertaining the royal visitor.

"He was such a dear boy," Mrs. Topping said, for the twentieth time, to the small circle of intimates who were drinking her lukewarm tea. Mrs. Towerly sat very still. But she was, even in her well-bred resignation, like one struck dumb with sorrow and frustration. For it was not in this instance possible to belittle her dear friend's triumph by a subtle disparagement of the visitor's social qualities. The Prince of Wales' position was, after all, unassailable.

"So sweet, so natural, so democratic, quite like an American," crescendoed Mrs. Topping.

Mrs. Towerly's prominent bosom rose and fell quickly and the jewelled hand that stirred her tea trembled.

"Why," continued Mrs. Topping, gazing directly at her old and dear friend, Mrs. Towerly. "Why, I remember the morning he left my house. We were walking before breakfast—just we two—in my garden. I remember because—" she broke off in a little shower of intimate, amused laughter,— "because my Scottie dog, Angus, was barking at his heels all the time. Why, Angus even snapped at the Prince's ankles!"

"How dreadful," shrilled a lady in grey velvet. "Whatever did the Prince say?"

"Why," she replied, "His Highness said "Lie down, sir, lie down.' "

"He said that?" Mrs. Towerly suddenly exclaimed, and then in a soft, reminiscent murmur looked through her dearest friend, back upon the triumphs of her own youth. "He said that? . . . Why, how very like Edward, his dear father!"

HUMILITY OF THE GREAT: It was the opening night of the Metropolitan Opera. The curtain had just fallen on the first act of Aida. The storm of applause had subsided and everyone in the orchestra, and parterre, settled comfortably hack in their plush chairs to inspect the occupants of the Diamond Horseshoe.

(Continued on page 94)

(Continued from page 60)

Instinctively every knowing eye in the house was focussed on box No. — at the left of the stage.

This was Mrs. Towerly's box, and Mrs. Towerly was in it. She was, indeed, a resplendent figure. As she waved her great black ostrich fan to and fro, it swept across her pearl festooned bosom like a cloud which scurries across the heavens obscuring for a dark moment the stars, the milky way and the full moon. Every uplifted eye in the orchestra, every pearl-handled opera glass in the parterre was trained upon her. Even in the Diamond Horseshoe, furtive and envious glances which scarcely dared seek her acknowledgement, were launched like timid flights of birds in the direction of her splendour.

No one noticed the wan little woman at her side. This was an obscure relative. (Perhaps to show that her democratic spirit was not to he measured by even the height of the social pinnacle upon which she sat, Mrs. Towerly always chose the occasion of the opening of the Opera to give a superlative pleasure to some remote and indigent relative.) Nor did anyone notice, except as chiaroscuro,—as background to Mrs. Towerly's full-bodied magnificence—the two black shadows in the rear of the box, which were, respectively, Mr. Towerly and the obscure relative's equally obscure husband.

But if Mrs. Towerly was perfectly and pleasantly aware of the attention she had merited, Mrs. Towerly's own cerulean glance was in turn riveted upon the empty box which faced her across the rosy haze of the opera house. This was Box No. — the loge of Mrs. Topping and it was now quite conspicuously empty. Its emptiness filled Mrs. Towerly with vague forebodings, for it meant one of two things. Either Mrs. Topping planned a late and impressive—and therefore theatrical entrance—or she would not appear at all. The latter contingency was even worse, for, leaving one's box empty on the opening night of the opera was a gesture too magnificently democratic for even Mrs. Towerly to consider. But even as she gazed, there was a stir in the hack of the vacant box, the red velvet curtains trembled, parted and Mrs. Topping entered. She took her chair as a queen assumes her throne. And all the eyes which had followed the languid flight of Mrs. Towerly's drooping black fan swung instantly, as though they were strung like beads on a single thread, away from Mrs. Towerly in the direction of Mrs. Topping.

For, if Mrs. Towerly were the moon and stars, Mrs. Topping was the sun and the sea. She was a blaze of gold lame, whole clusters of frosty diamonds broke like white caps among the seagreen emeralds that billowed on her breast.

And Mrs. Topping was notably accompanied. Her guest, in velvet and old lace was the fabulously exclusive English Duchess of A-. And at the hack of the box, his ruddy heard glowing dully above the snowy bosom of his shirt, was the Duke, exchanging whispered confidences with Mrs. Topping's husband.

Mrs. Topping, socially, picturesquely, historically, had won the laurels for the opening of the Opera.

And Mrs. Towerly who was as sensitive to the social triumphs of others as she was to draughts on the back of her neck, realized it all too well. She also knew that the sudden expressive immobility of her face had not escaped the penetrating side-long glances of her obscure relative, who, gazing at her from the corner of her small damp orbs, was suddenly overwhelmed with fright and shame, aware that her own presence on this Night of Nights had been the unhappy cause of her famous kinswoman's social eclipse.

But Mrs. Towerly, with a majestic smile, inclined her head toward her obscure relative, and said with philosophic conviction.

"My dear Millie, Fanny Topping has the soul of a snob. She has plainly forgotten what I am too humble to permit myself to forget: that we were all born naked!"

THE COUP DE GRACE: Ever since Mrs. Topping had entertained the Prince of Wales and the Duke and Duchess of A-, there had been a noticeable coolness between Mrs. Topping and her life-long friend, Mrs. Towerly. It was not that these two great ladies ceased to observe the gracious outward semblance of affection and devotion but rather that the too poignant sweetness of their public encounters, their forced and radiant smiles, their exaggerated solicitude for each other's health and advancing age, evidenced all the classic symptoms of secret feminine rivalry. And, at length, even those who plucked with anxious, plebeian fingers at the outer-fringe of society had begun to remark with what extraordinary frequency the parties, dinners and balls of the one conflicted with the parties, dinners and balls of the other.

Therefore, it became a topic of wonderment among their intimates that Mrs. Towrerly, knowing months in advance of Mrs. Topping's forthcoming Harlequin Ball, had nevertheless set up no party opposition. She had, she said, merely invited a handful of guests to dinner and would be charmed to bring them on to Mrs. Topping's.

The night of the ball, which was given in the gold and crystal room of the Topping mansion, arrived.

With a broad-minded consideration of the biological expansion of the Social Register, Mrs. Topping had sent out six hundred more than the traditional four hundred invitations. With alacrity, and with hardly an exception, they had all been accepted.

Mrs. Topping, receiving at the head of the broad staircase which led to the ballroom, surveyed a plentiful and glittering gathering. She surveyed them, however, with an unimpassioned and not entirely complacent gaze, for Mrs. Towerly, her dearest, her lifelong friend, had not yet put in an appearance.

Shortly before midnight, however, Mrs. Towerly arrived and with her she brought The Crown Prince and Princess of S-. Mrs. Topping, forgetting her regal aloofness, stepped forward to greet the new arrivals, beaming. "How very nice of you," said Mrs. Topping, "to come to my party." She led Mrs. Towerly and her guests to the entrance of the ballroom still chatting with grateful animation.

(Continued on page 98)

(Continued from page 94)

They stood there for a minute looking at the crowded floor where, to the alternating strains of two orchestras, hundreds of couples whirled and swayed in a mêlée of scent and jewels. And then Mrs. Topping, recalling her duties as hostess, turned to go.

To this day no one knows whether Mrs. Towerly realized that her dear friend had not quite gone. But Mrs. Topping and several other guests saw Mrs. Towerly turn to her eminent companions, with a deprecatory wave of her hand, and quite distinctly heard her say, "Poor Fanny. There's positively nobody here". ...

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now